I didn’t answer. I let him go on with his fancies, and I wondered what I was going to do when he was gone and I should no longer come to Oakland Hall.

“I’ve been thinking of something,” he said.

“I reckon the time has come. Joss should be told. He ought to start thinking about coming over now. It’ll take him time. You can’t expect him to catch the first ship. He’ll have things to arrange. With out Joss the Company will be in need of a bit of organizing.”

You want to write to him? ” I said. I took paper and pen and sat down by the bed.

“What do you want me to say?”

“I’d like you to write it in your own way. I want it to be a letter from you to him.” - “But…”

“Go on. It’s what I want.” So I wrote:

Dear Mr. Madden, Mr. Ben Henniker has asked me to write to you to tell you he is very ill. He wants you to come to England. It is very important that you should leave as soon as possible. Yours truly, Jessica Clavering.

Read it to me,” said Ben, and I did.

“It does sound a bit unfriendly,” he commented.

“How could it be friendly when I haven’t met him?”

“I’ve told you something about him.”

“I suppose it doesn’t make me feel particularly friendly.”

Then I haven’t told you the right things and I’m to blame.

When you meet him, you’ll feel like all women do . you’ll see. “

I’m not a silly little peahen to goggle at the magnificent peacock, you know, Ben. “

That set him laughing so much that once again I was afraid it might be bad for him.

When he was quiet he lay back smiling happily, as through I thought, he had discovered a rich vein of opal.

“Anyone would think you’d found the Green Rash,” I told him, and a strange expression crossed his face. I could not guess what he was thinking.

He rallied a little after that and in due course I received a reply from Josslyn Madden. It was addressed to Miss Jessica Clavering at Oakland Hall, and Mr. Wilmot handed it to me on a silver salver when I arrived.

I saw the Australian postmark and the bold handwriting, and I guessed from whom it came, so I took it up to Ben and told him that Joss Madden had answered my letter.

I opened it and read aloud:

Dear Miss Clavering, Thank you for your letter. By the time you receive this I shall be on my way. I shall come immediately to Oakland Hall when I arrive in England.

Yours truly, J. Madden.

“Is that all he says ?” cried Ben querulously.

“It’s enough,” I replied.

“All he has to tell us is that he is on his way.”

April had come. I should be nineteen in June.

“You’re growing up,” said my grandmother.

“How different it might have been. We should have done our duty by you and you would have come out with dignity. Here … in this place … what can we hope for? There isn’t even a curate for you. Mind you, your fondness for low company might exclude you from such as Miriam has turned to.”

“Miriam is very happy, I think.”

“I’m sure she is … wondering where her next meal is coming from.”

“It’s not as bad as that. They have enough to eat. She enjoys managing and I know she is much happier than she was here.”

“Oh, she was glad enough to get someone to marry her … anyone … it didn’t matter who. I hope you’re not going to get into that desperate state.”

‘you need have no anxieties on that score,” I retorted.

I was feeling very sad because I knew that Ben’s health ‘it V. for the worse; he was visibly deteriorating of what would happen when he died and I pro sited Oakland. The future stretched out drearily as I was still doing what my grandmother called des expected of people in our position, even though Are in such reduced circumstances. That meant taking the poor dusters and the preserves which had not turned as well as my grandmother had expected them to, taking harge of a stall at the church fete, attending the sewing class held at the vicarage, putting flowers on the graves, helping decorate the church and such activities, I could see myself growing old and sour as Miriam had been before she married her curate-but even she had had him in the background, I was no longer very young. I was now a woman and the older I grew the more quickly would the years slip by The days began ordinarily enough with prayers in the drawing-room where the family assembled with the servants while my grandmother, as I once irreverently observed to Miriam, gave the Almighty His instructions for the day.

“Do this …” and “Don’t do that…” By force of habit I counted up the injunctions.

That April Mrs. Jarman had been delivered of another child and Jarman was more melancholy than ever. Nature, he told me, showed no signs of curbing her generosity. My grandmother sharply retorted that he was not so simple that he did not know that a little restraint might ease the situation. He was indeed Poor Jarman; he looked at my grandmother with such reproach that he made me want to laugh.

“Talk of Poor Jarman,” she said to me sharply.

“I think it’s a case of Poor Mrs. Jarman.”

In an outburst of generosity she packed a basket for the fertile lady and even put in a pot of raspberry jam which had not started to go mouldy, a small chicken, and a flask of broth.

You can take this over to Mrs. Jarman, Jessica,” she said.

“After all, her husband does work for us. Take it while he is working, for I am sure he seizes the best of everything for himself and she needs nourishment, poor woman.”

That was how on a breezy afternoon in late April I came to be walking over to the cottage where the Jarmans lived, a basket on my arm, thinking as I went of Ben and wondering how soon the day would come when I went over to Oakland Hall and found that he had left it.

Outside the Jarman cottage was a muddy pond and a scrap , of garden overgrown with weeds. It was strange that Poor Jarman, who spent his days making other people’s gardens beautiful should so neglect his own. I contemplated that they could have grown some flowers there, or perhaps some vegetables, but instead of daffodils and flowering shrubs there were little Jarmans playing games which seemed to involve the maximum of noise, confusion, and an abundance of litter.

One of the young ones who must have been about three years old had a small flowerpot into-which he was shovelling dirt and turning it out into neat little mounds which he patted with hands understandably grimy, after which operation he rubbed them over his face and down his pinafore. Two others were tugging at a rope and another was throwing a ball into the pond so that when it bounced a spray of dirty water rose, splashing him and anyone near to the immense delight of those who were thus anointed.

There was a brief silence as I approached, all eyes on the basket, but as I went into the cottage the noise broke out again.

I called out: “Good afternoon, Mrs. Jarman.”

One stepped straight into the living-room, and I knocked on a door which I knew from previous visits to be that of the connubial bedchamber. There was a spiral staircase leading from the room to two rooms upstairs which were occupied as sleeping quarters by the ever-increasing tribe.

Mrs. Jarman was in bed, the new baby in a cradle beside her. She was very large. Like a queen bee, I had once remarked to Miriam, and indeed Nature had clearly furnished her for a similar destiny.

“Another little girl, Mrs. Jarman,” I said. , “Yes, Miss Jessica,” said Mrs. Jarman, rolling her eyes reproachfully up to the ceiling as though Providence had whisked this one into the cradle when she wasn’t looking, for she shared Poor Jarman’s complaint that it was Nature at her tricks again.

The little girl was going to be called Daisy, she told me, and she hoped God would see fit to bless her.

“Well, Mrs. Jarman,” I said, ‘you have your quiverful and that’s supposed to be a blessed state. “

“It’ll mean getting another bed up there in time,” she said.

“I only hope the Lord sees fit to stop with Daisy.”

I talked for a while and then came out of the house to where the noise seemed to have increased. The maker of dirt mounds had had enough of them and was cheerfully kicking them down to the pond. The ball went into the pond and the Jarman who had thrown it shrugged his shoulders and walked away.

I was about to cross the road when the mound-maker having seen the ball go into the pond decided to retrieve it. He walked in, reached for the ball and fell flat on his face.

The other children were all watching with interest, but none of them thought of getting the child out. There was only one thing for me to do because he was in imminent danger. I waded into the pond, picked up the little Jarman and angrily strode with him on to dry land.

As I stood there with the child in my arms I was aware of a man on horseback watching the scene. The horse looked enormous, so did the man; it was like a centaur or some legendary creature.

An imperious voice said: “Can you tell me the way to Oakland Hall?”

The eldest Jarman present, who must have been about six, shouted: “Up the road there…”

The man on horseback was looking straight at me expecting the only adult to give the answer.

I said: “You go straight up the road, turn to the right and you will see the gates a little way along the road.”

“Thank you.”

He put his hand into his pocket and brought out some coins which he threw at us.

I was furious. I hastily put down the little Jarman and stopped to pick up the coins with the intention of throwing them back at him, but before I could reach them two Jarmans had swooped on them and had run off as fast as they could with their prize.

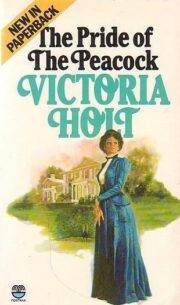

"The Pride of the Peacock" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Pride of the Peacock". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Pride of the Peacock" друзьям в соцсетях.