“We can,” said Joss.

“Ben, you’re outrageous.”

“I know,” he replied with a hoarse chuckle.

“But I never wanted anything in my life so much as I want this. I can only die happy if I see you two married first. I just know it’s right. I can see into the future.”

I thought: He’s mad. Surely the old Ben would never have talked like this.

“Now listen to me,” he went on.

“I’ve made all the arrangements. I’m leaving everything to you … except for a few minor legacies … that’s if you’re married.”

“And if we don’t?” said Joss.

“My dear Joss, you get nothing… nothing.”

“Now look here…”

“You can’t argue about a man’s estate when he’s on his deathbed,” said Ben, and there were lights of mischief in his eyes.

“You don’t get a thing … either of you … unless you marry. That’s plain fact.

Joss, do you want to see the Company pass out of your hands ? “

You couldn’t do that. “

“You’ll see. Jessica, do you want to spend your days in the Dower House with that virago of a grandmother … looking after her when she gets more fractious … or do you want a life of excitement and adventure? It’s for you to choose. You’re right, both of you, when you say I can’t force you. I can’t. But I can make it very uncomfortable for you if you don’t do what I want.”

We looked at each other across the bed.

This is absurd,” I began, but Joss Madden did not answer. I was aware that he was contemplating the loss of the Company. Ben had conjured up a picture for me too. I saw myself ten … twenty years hence, growing pinched about the lips as Miriam had begun to look … decorating the church, taking baskets to the poor, growing old, growing sour because life had passed me by.

Ben knew what I was thinking.

“It’s a gamble,” he said.

“Don’t forget that. What are you going to do?”

He lay back on his pillows and closed his eyes. I stood up and said I thought he was tired.

He nodded. "I've given you something to think about, haven’t I ? ” He seemed full of secret amusement.

Joss Madden came with me to the door.

I said: “I’ll go by the back way across the bridge and the stream.”

“I’m afraid this has been a shock to you,” he said.

"You are right,” I answered.

“How could it be otherwise?”

“I should have thought young ladies in your position often had husbands chosen for them.”

"That does not make the position any more acceptable."

“I’m sorry I’m so repulsive to you. You have made that very clear.”

“I don’t think you showed any enthusiasm for the proposed marriage.”

“I suppose we are both the sort of people who would want to choose for themselves.”

“I think Ben must be losing his senses.”

“He believes he’s in full possession of them. You Claverings have cast a spell on him. Ifs those grand antecedents of yours with your ancestral home and so on. He wants your blue blood to be brought into his family.”

“He will have to think of another way.”

“I hardly think he can if you refuse to comply.”

‘you surely don’t mean that you would ? “

I had stopped short in my amazement and looked at him searchingly. His lips twisted into a wry smile. There’s a great deal at stake for me,” he said.

I said shortly: “I’ll leave you here. Goodbye.”

“Au revoir,” he called after me as I sped across the grass.

I went back to the Dower House in a kind of daze. As I came into the hall the familiar smell of lemon wax struck me forcibly, although I should have become accustomed to it after all these years because it was always there. My grandmother used to say that even though we had come down in the world we must show people that we had not given up our standards and there was no excuse for even the most humble dwelling not to be spotlessly clean. There was a bowl of flowers in the hall-lilacs and tulips arranged by my grandmother neatly and without artistry. I could hear voices in the drawing-room-those of my grandmother and Xavier, and I wondered whether my grandfather was there in his usual role of penitent. I paused for a moment and contemplated the confusion which would result if I opened the door and announced that I had had a proposal of marriage and would in due course be leaving for Australia. That would scarcely be true, for I could hardly call it a proposal since the intended bridegroom was more reluctant than prospective. It then occurred to me how deeply I should have enjoyed confronting them with such news.

I went to my room-a pleasant little one with a picture of one of our ancestors on the wall. She had once graced the gallery at Oakland. My grandmother had been hard put to it to find suitable spots in which to accommodate all the pictures in the Dower House. With a characteristic desire to improve us all she had distributed ancestors with considered judgement. I had Margaret Clavering, circa x669, a handsome young woman with a hint of mischief in her eyes. I had never heard exactly what she did, but I knew that it was something shocking, but in such a manner as to make even my grandmother’s lips twitch with amusement.

Her misdemeanour must therefore have been committed in high places-I suspected the King himself was involved as indeed he was with so many.

Even so, poor Margaret did come to an untimely end when she was thrown from her horse while escaping with a lover from one of her husbands-she had apparently had many of the former and three of the latter.

In my grandfather’s room gamblers looked down from the walls. I always thought they were a jolly-looking crowd, all those wastrel Claverings, and might prove an inducement rather than a deterrent; and they certainly looked nicer to know than the virtuous saviour of our fortune from the eighteenth century who looked down primly, and I am sure approvingly, on my grandmother.

The four-poster bed was a little overpowering for my small room; and there was one chair with the tapestry seat and back worked by another ancestress, and the fellows of this were distributed round the house.

There was also a beautiful Bokhara rug-another relic of Oakland. I saw all these articles with greater clarity it seemed than before. I suppose because Ben had suggested that if I were wise I should soon be leaving them and if I were not I might be with them for the rest of my life.

I couldn’t stay long in my room. There was one to whom I could talk, though the idea of doing so a few months ago would have been out of the question - Miriam. I ran out of the house and went along to Church Cottage -the name of the tiny house at one end of the vicarage grounds. It looked quite pretty, I thought, with the shrubs on either side of the crazy paving path which led to the front door.

Miriam was at home. How she had changed! She looked several years younger, and there was a new dignity about her. I did not need to ask if she was happy.

I stepped straight into the livingroom; there was only a kitchen and this room on the lower floor and from the livingroom a staircase twisted up into two bedrooms above. Every thing was highly polished and a bowl of azaleas and green leaves stood on the red table doth there were chintz curtains at the window and another bowl of flowers on the hearth, on either side of which were two chimney seats. One or two of Miriam’s possessions-brass candlesticks and silver ornaments-looked rather incongruous, but charming, in this humble room.

Miriam’s hair was dressed in a less severe style than she had worn it before and she looked very domesticated in her starched print gown as she carried a duster in her hand.

"Oh Miriam,” I cried.

“I had to see you. I wanted to talk.”

That she was pleased, there was no doubt.

“I’ll make some tea,” she said.

“Ernest is out. The vicar works him too hard.”

I put my head on one side and studied her.

“You’re a joy to behold,” I said.

“A walking advertisement for the married state.” It was true.

How she had changed! She was indulgent, in love with her curate and with life; and the fact that she had turned her back on this blissful state for so long only made her appreciate it more now that she had achieved it.

“I’ve had a proposal,” I blurted out.

“Well, a sort of proposal.”

Little lights of fear showed in her eyes.

“Not… someone at Oakland?”

“Yes. ” Oh, Jessica! ” Now she looked like the old Miriam, for my words had transported her back in time to that other occasion when another Jessica had had a proposal from a visitor to Oakland.

“Are you sure.. ”

"No,” I said.

“I’m not.”

She looked relieved.

“I should be very, very careful.”

“I intend to be. Miriam, suppose you hadn’t married Ernest … suppose you had gone on as you were…”

I saw the look of horror in her face.

“I couldn’t bear to think of that,” she said firmly.

“Yet you hesitated so long.”

“I think if was a matter of plucking up courage.”

“And even if it hadn’t worked out so well with Ernest would you still be glad you left?”

“How could it possibly not have turned out well with Ernest?”

“You didn’t always think that, did you, or you would have done it before.”

“I was afraid ” Afraid of your mother’s sneers and prophecies. They don’t worry you now. “

“I don’t care how poor we are … and we can manage. I’ve discovered I’m a good manager. Ernest says so. And even if things hadn’t turned out so well, to tell the truth, Jessica, I should have been glad to get away from the Dower House.”

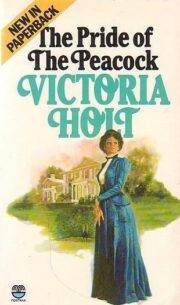

"The Pride of the Peacock" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Pride of the Peacock". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Pride of the Peacock" друзьям в соцсетях.