The King had also given me various beautifully-wrought articles for my entourage, and while I was admiring these I heard a rumble of thunder.

The brilliant sky had become overcast and I immediately thought of all the poor people whom I had seen on the road from Paris to Versailles and who had come to see the wedding celebrations, for there was to have been a firework display for them as soon as it was dusk; and now, I thought, it is going to rain and it will all be spoilt.

During the storm I was given a little insight into the peculiarities of the aunts. As I went into my apartment I saw’ Madame Sophie talking to one of my women eagerly and in the most friendly fashion. This was strange, because when I had been presented to her she had scarcely spoken to me and I had heard that she rarely uttered a word and that some of her servants had never heard her speak. Yet there i she was, talking intimately to the poor woman, who seemed , quite bewildered and uncertain how to act. As I came forward Madame Sophie took the woman’s hands and squeezed them tenderly. When she saw me she cried, how was I? how did I feel? was I fatigued? There was going ; to be a horrid storm and she hated them. The words came tumbling out. Just then a clap of thunder seemed to shake the palace and Sophie put her arms “bout the woman to whom she had been talking so affectionately and embraced her. It was a most extraordinary scene.

It was Madame Campan who told me later that Madame Sophie was terrified of thunderstorms and when they came her entire personality changed. Instead of walking everywhere at great speed, leering at everyone from side to side—’like a hare,” Madame Campan described it—in order to recognise people without looking at them, she talked to everyone, even the humblest, squeezing their hands and even embracing them when her terror was at its greatest pitch. I was to learn a great deal about my aunts, but like everything else, I learned it too late.

As soon as the storm was over, Sophie behaved as before, speaking to no one, running through the apartments in her odd way. Madame Campan, in whom Aunt Victoire had confided freely over many years, told me that Victoire and Sophie had undergone such terrors in the Abbey of Fontevrault, to which they had been sent as children to be educated, that it had made them very nervous and they retained this nervousness even in maturity. They had been shut in the vaults where the nuns were buried and left there to pray, as a penance; and on one occasion they had been sent to the chapel to pray for one of the gardeners who had gone raving mad. His cottage was next to the chapel, and while they were there alone praying, they had to listen to his bloodcurdling screams.

“We have been given TO paroxysms of terror ever since,” Madame Victoire explained.

Although the thunder died away, the rain continued, and as I had feared, the people of Paris who had come to Versailles to see the fireworks were disappointed. There would be no firework display in such weather. Another bad omen!

In the Galerie des Glaces the King was holding a reception and there we were all assembled. The magnificence of the Galerie on that occasion was breathtaking; later I became accustomed to its splendour.

I remember the candelabra-gilded and glittering—each of which carried thirty candles so that in spite of the darkness it was as light as day. With the King, my husband and I sat at a table which was covered with green velvet and decorated with gold braid and fringe, and we played cavagnole which fortunately, with great fore sight, I had been taught to play, and I could play this silly sort of game far better than I could write. The King and I smiled at each other over the table while the Dauphin sat sullenly playing as though he despised the game which of course he did. While we played, people filed past to watch us, and I wondered whether we ought to smile at them, but as the King behaved as though they did not exist I took my cue from him. There were among the spectators several uninvited guests, for only those who had received special invitations should have been there, but some of those who had not been driven home by the storm, deter mined to compensate themselves for the loss of the firework display, broke the barriers and forced their way in to mingle with the guests. The ushers and guards found it quite impossible to restrain them, and as no one wanted any unfortunate displays of anger on this occasion, nothing was done.

When the reception in the Galerie des Glaces was over we went for supper to the new opera house which the King had had built to celebrate my arrival in France. As we crossed to the opera house the Swiss Guards, splendid in starched ruffs and plumed caps, together with the bodyguards, equally colourful in their silver-braided coats, red breeches and stockings, made a guard for us.

The real function of this beautiful opera house had been of disguised.

A false floor had been set up to cover the seats, and on this was a table decorated with flowers and gleaming glass. With great ceremony we took our places: the King at the head of the table, myself on one side of him, my husband on the other, and next to me and for this I was thankful my mischievous younger brother-in-law, the Comte d’Artois, who was very attentive to me and proclaimed him-J self to be my squire, implying in his outrageous way that he would uphold the honour of France in the place of the Dauphin at any rime I wished! He was bold, but I had liked him from the moment we met.

On the other side of Artois was Madame Adelaide, clearly revelling in an occasion like this, keeping an eye on her sisters—Sophie next to her, Victoire opposite, next to Clothilde—and trying to talk to me over Artois, her sharp eyes everywhere. She hoped that she and I would be able to talk together in her apartments, intimately. It was imperative. Artois, listening, raised his eyebrows to me when Adelaide could not see, and I felt that we were allies. At the extreme end of the table—for she was of the lowest rank of the twenty-one members of the royal family—was the young woman who had interested me so much when I had first been presented to my new relations: the Princesse de Lamballe. She smiled at me very charmingly and I felt that with her and the King and my new champion Artois as my friends I need not be apprehensive about my future.

I was far too excited to eat, but I noticed that my husband had a good appetite. I had never known anyone who could appear so oblivious of his surroundings. While the King’s Meat (as the numerous dishes were called) was being brought in with the utmost ceremony he might have been sitting alone, for his one interest was the food, on which he fell as though he had just returned from a hard day’s hunting.

Noticing his grandson’s voracious appetite the King said to him quite audibly: “You are eating too heartily. Berry. You should not overload your stomach tonight of all nights.”

My husband spoke then, and everyone listened—I suppose because they heard his voice so rarely.

“I always sleep better after a good supper,” he said.

I was aware of Artois beside me suppressing his amusement, and many of the guests seemed suddenly intent on their plates; others had turned and were in deep conversation with then-neighbours, faces turned away from the head of the table.

The King looked at me rather sadly; then he began to talk over the Dauphin to the Comte de Provence.

The next part of the proceedings was so embarrassing that even now I do not care to think about it. The night had come. When I looked across the table and caught my husband’s eye he looked uneasy and turned away. I knew then that he was as disturbed as I was. I was aware of what was expected of me that night, and although I did not look for ward to it with any great pleasure, I was certain that, how ever distasteful it was, the result of what would happen would give me my dearest wish. I should have a child and any discomfort was worthwhile if I could become a mother.

Back to the Palace we went and the ceremony of putting the bride and groom to bed began. The Duchess de dart res the married lady of highest rank, handed me my nightgown; and I was led to the bedchamber where my husband, who had been helped into his nightshirt by the King, was waiting for me. We sat up in bed side by side, and all the time my husband had not looked at me. I was not sure whether he thought the whole affair incredibly silly or was just sleepy after all the food he had eaten.

The curtains were drawn back so that everyone could see us and the Archbishop of Rheims as he blessed the bed and sprinkled it with holy water. We must have appeared to be a strange little couple both so young, little more than children: myself flushed and apprehensive, my husband bored. In truth we were two frightened children.

The King smiled at me wistfully as though he longed to be in the Dauphin’s place, and then turned away to leave us together. Everyone bowed and followed him out and my attendants drew the bed curtains shutting me in alone with my bridegroom.

We lay in bed looking at the hangings. I felt lonely shut in with a stranger. He did not attempt to touch me; he did not even speak to me. There I lay listening to my heartbeats or were they his waiting . waiting.

This was what all the fuss of preparation had been about the solemn ceremony in the chapel, the glittering banquet, the public’s peepshow. I was to be the mother of the Enfants de France; from my activities in this bed I was to produce the future King of France.

But nothing happened . nothing. I lay awake. It must be soon, I said to myself; but still I lay and so did he . in silence, making no move to touch me, speaking no word.

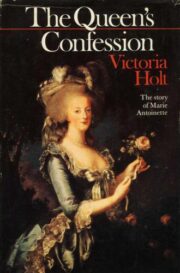

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.