This state of affairs continued, while I received angry letters from my mother, who cared much more than I did about the humiliation of my position.

And as I entered the second year of my marriage another controversy arose which made everyone forget the tragedy of our bedchamber.

My quarrel with Madame du Barry had been brewing ever since the aunts had told me of her true position at Court. I did not understand then that I should have been wiser to form an alliance with her than with the aunts. They, unknown to me, had resented my coming from the first.

They had been strongly against the Austrian alliance and were no real friends to me, whereas this woman of the people, vulgar as she might have been, had a good heart, and although Choiseui had arranged the marriage, and he was her enemy, she bore no animus towards me. Had I shown her the slightest friendliness she would have returned it doubly. But I was foolish. Egged on by the aunts, I continued to ignore her; I used my gift of mimicry and gave Hide imitations of her which caused a great deal of amusement and which, naturally, were reported to her. I could imitate her mannerisms, her vulgar laughter, her silly lisp and I did, exaggerating them ever so slightly to increase the amusement.

It did not occur to me that she must be wiser than I to have climbed to the top place at Court from the streets of Paris. The King doted on her; he allowed her to perch on the aim of his chair at a council meeting, to snatch papers from him when she wanted his attention, to call him “France’ in an insolently familiar way. All this he found amusing, and if anyone criticised her he would say, ” She is so pretty and she pleases me and that ought to be enough for you. ” So everyone realised that if they wished to remain in die King’s good graces they must please Madame du Barry. But I was in his good graces. I did not have to con form to ordinary standards so I thought and I made up my mind that I would never seek the friendship of a street-woman, no matter if she was the King’s mistress. So I behaved as though I could not see her. Often she would seek the opportunity to present herself before me but she could not speak to me until I spoke to her etiquette for bade it, and even she had to bow the knee to etiquette. So every time, I ignored her.

Although she was not a woman to bear rancour she was no respecter of persons either. She gave me the nickname of Little Austrian Carrots, and as this was taken up by others I grew very angry, and increased my imitations of her crudities and continued to look through her every time we met. This snubbing because so obvious that soon the whole Court was talking of it, and Madame du Barry became so incensed that she told the King she could endure it no longer and that Little Carrots should be ordered to speak to her.

The King, hating trouble, was annoyed, and I lacked the sense to realise that he was angry with me for making it. His first action was to send for Madame de Noailles, and naturally he did not come straight to the point. Madame de Noailles, in a state of fluster, reported to me immediately the King dismissed her. He had begun, she said, by saying one or two complimentary things about me, and then he had criticised me.

Criticised! ” cried Madame de Noailles in horror. you have evidently displeased him greatly. You are talking too freely and such chatter can have a bad effect on family life, he says. In ridiculing members of the King’s household you displease him.”

Which members? “

“His Majesty named no specific one, but I think that if you would say a few words to Madame du Barry you would please her, and she would report her pleasure to the King.”

I pressed my lips firmly together. Never! I thought, I’ll not allow that street-woman to dictate to me.

Foolishly I went at once to the aunts and told them what had happened.

What excitement there was in their apartments Adelaide clucked and clicked her tongue.

“The insolence of that putain. So the Dauphine of France must be dictated to by prostitutes!” She believed the woman was a witch and had the King under her spell. She could find no other reason for his behaviour. But how right I was to come to them! They would protect me from the King, if need be. She would think up a plan and in the meantime I must behave as though Madame de Noailles had not spoken to me. I must on no account give way to that woman.

The Abbe saw my indignation and asked the cause of it, so I told him; and he went straight to Mercy and told him. Mercy immediately saw the dangerous implications and sent an express messenger to Vienna with a full account of what had taken place.

My poor mother! How she suffered from my stupidities! One little word was all that was needed and I would not give it. I was certain that I was right then. My mother was a deeply religious woman who had always deplored light behaviour in her own sex and had set up a Committee of

Public Morals so that any prostitute found in Vienna was imprisoned in a corrective home; I was sure she would understand and approve my action. I could not see that my refusing to speak to the King’s mistress was a political issue simply because she was the King’s mistress and I was who I was. I did not see the difficult position in which I was placing my mother. She either had to deny her strict moral code or displease the King of France; and although she might have been a moralist she was first of all an Empress. I should have realised the gravity of the situation when she did not write to me herself but instructed Kaunitz to do so.

The express messenger returned with a letter from him addressed to me.

He wrote:

“To refrain from showing civility towards persons whom the King has chosen as members of his own circle is derogatory to that circle; and all persons must be regarded as members of it whom the monarch looks upon as his confidants no one being entitled to ask whether he is right or wrong in doing so. The choice of the reigning sovereign must be unreservedly respected.”

I read this through and shrugged my shoulders. There was no express order to speak to Madame du Barry. Mercy was with me when I received the letter and he read it also.

“I trust,” he said, ‘that you realise the seriousness of this letter from Prince von Kaunitz? “

They were all waiting for me to speak to the woman, because it was not long before the whole Court knew that the King had instructed Madame de Noailles. They thought this was going to be defeat for me, and I was determined that it should not be. I could be stubborn when I thought I was right and I certainly believed I was right about this.

Madame du Barry expected me to speak to her. At every soiree or card party she would be waiting expectantly; and every time, I would find some excuse to turn away just as she was approaching Needless to say, the Court found this most diverting Adelaide and her sisters were delighted with me. They would throw sly looks in my direction whenever we were in public and Madame du Barry was near. They congratulated me on my resistance. What I did not realise was that in flouting the King’s mistress I was flouting the King; and this could not be allowed to go on.

The King sent for Mercy, and Mercy came to talk to me, as he said, more seriously, than he ever had before.

“The King has said, as clearly as it is possible for him to say it, that you must speak to Madame du Barry.” He sighed.

“When you came to France, your mother wrote to me that she had no wish for you to have a decisive influence in state affairs. She said that she knew your youth and levity, your lack of application, your ignorance and she knew too of the chaotic state of the French government. She did not want you to be blamed for meddling. Believe me, you are meddling now.”

“In state matters! Because I refuse to speak to that woman!”

“This is becoming a state matter. I beg of you to listen carefully.

Frederick the Great and Catherine of Russia are seeking to divide Poland. Your mother is against it, although your brother the Emperor is inclined to agree with Prussia and the Russians. Morally your mother is right, of course, but she will be forced to give way, as not only your brother but Kauoitz is for partition. Your mother is afraid of French reaction to this. If Prance decided to oppose j partition, Europe could be plunged into war. ” ” And what has this to do with my speaking to that woman? ”

” You will learn that the most foolish actions can spark off disasters.

Domestic matters have their effect on state affairs. Your mother is particularly desirous at this time of not offending the King of France. He looks to her to settle this silly quarrel between two women which is being discussed throughout the country and perhaps in others.

Can you not see the danger? “

I could not. It seemed so absurd.

He gave me a letter from my mother and I read it white he watched me.

“They say you are at the beck and call of the Royal ladies. Be careful. The King will get weary of it. These Princesses have made themselves odious. They have never known how to win their father’s love nor the esteem of anyone else. Everything that is said and done in their apartments is known. In the end you will have to bear the blame for it and you alone. It is for you to set the tone towards the King—not them.”

She does not know, I thought. She is not here.

I must write to the Empress at once,” said Mercy, ‘and tell her of my interview with the King. Meanwhile I implore you to do this small thing. Just a few words. That is all she asks. And is it much?”

With a woman of that kind it would not stop at a few words. She would always be at my side. “

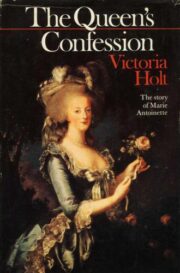

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.