I am sure you would know how to prevent that. “

“In matters of good behaviour I have no need to ask the advice of anyone,” I said coldly.

“That is true, I know. But would you feel some remorse if the Austro-French alliance broke down because of your behaviour?”

“I would never forgive myself.” A smile cracked his old face and he looked almost human.

“Now I know,” he said, ‘that you will take the advice of your mother and those who wish you well. “

But I could not learn my lessons. When I was with the aunts I told them of my conversation with Mercy. Adelaide’s eye flashed fire. It was immoral, she declared.

“I have no choice. My mother wishes it. She is afraid that the King will be displeased not only with me but with Austria.”

“The King often needs saving from himself ” I must do it,” I said.

Adelaide was quiet; her sisters sat looking at her expectantly. I thought: Even she accepts the position now.

I should have known better.

It was all over the Court. Tonight the Dauphine will speak to the du Barry.

“La guerre des femmes is over, with victory for the mistress.”

Well, anyone who wagered against that result was a fool. But it would be amusing to see the humiliation of Little Carrots and the triumph of

the du Barry. In the salon the ladies stood waiting for my approach. My custom was to pass among them addressing a word to each in turn and among them was Madame du Barry. I was aware of her, waiting eagerly, her blue eyes wide with only the faintest trace of triumph. She did not wish to humiliate me, only to ease a situation which was intolerable to her.

I was uneasy, but I knew I had to give in. I could not flout the Ring of France and the Empress of Austria. Only two people separated her from me. I was steeling myself; I was ready.

Then I felt a light touch on my arm. I turned and saw Adelaide, a sly triumph in her eyes.

“The King is waiting for us in Madame Victoire’s apartments” she said.

“It is time for us to be going.”

I hesitated. Then I turned, and with the aunts, left the salon. I was aware of the silence in the room. I had snubbed the du Barry as never before.

In their apartments the aunts were twittering with excitement See how we had outwitted them! It was unthinkable that I Berry’s wife should speak to that woman.

I waited for the storm and I knew I should not have to wait long.

Mercy came to tell me that the King was really angry. He had sent for him and said coldly that his plans did not seem effective, and he himself would have to take a hand.

“I have sent an express messenger to Vienna,” Mercy told me, ‘with a detailed account of what has happened. ” My mother herself wrote to me:

“The dread and embarrassment you are showing about speaking to persons you are advised to speak to is both ridiculous and childish. What a fuss about saying Good Day to someone! What a storm about a quick word perhaps about a dress or a fan! You have allowed your self to become enslaved and your duty can no longer persuade you. I myself must write to you about this foolish matter. Mercy has told me about the King’s wishes and you have had the temerity to fail him! What reason can you give for behaving in such a way? You have none. It is most unbecoming to regard Madame du Barry in any other light than that of a lady whom the King honours with his society. You are the King’s first subject and you owe him obedience. You should set a good example; you should show the ladies and gentlemen of Versailles that you are ready to obey your master. If any intimacy were asked of you, anything that were wrong—neither I nor any other would advise you to do it. But all that is asked is that you should say a mere word-should look at her pleasantly and smile—not for her sake, but for the sake of your grandfather, who is not only your master but your benefactor.”

When I read this letter I was bewildered. It seemed that everything my mother stood for had been thrust aside for the sake of expediency. I had behaved as she had brought me up to behave and it seemed I was wrong. This letter was as clear a command as she had ever given me. I wrote to her, for she expected an answer:

“I do not say that I refuse to speak to her, but I cannot agree to speak to her on a fixed hour or a particular day known to her in advance so that she can triumph over that.” I knew that this was quibbling and that I was defeated.

It was New Year’s Day when I spoke to her. Everyone knew it would be that day and they were ready. In order of precedence the ladies filed past me and there among them was Madame du Barry.

I knew nothing must prevent my speaking this time. The aunts had tried to advise me against it but I did not listen to them. Mercy had pointed out to me that while they railed against Madame du Barry in private, they were friendly enough to her face. Had I not noticed this? Should I not be a little wary of ladies who could behave so?

Now we were face to face. She looked a little apologetic as though to say: I don’t want to make it too hard for you, but you see it had to be done.

Had I been sensible I should have known that was how she sincerely felt; but I could only see black and white. She was a sinful woman, therefore she was wicked all through. I said the words I had been rehearsing: “II y a bien du monde aujowd’hm a Versailles.”

It was enough. The beautiful eyes were full of pleasure, the lovely lips smiled tenderly; but I was passing on.

I had done it. The whole Court was talking of it. When I saw the King he embraced me; Mercy was benign;

Madame du Barry was happy. Only the aunts were displeased;

but I had noticed that Mercy was right; they were always affable to Madame du Barry in person, while they said such wounding things behind her back.

But I was hurt and angry.

“I have spoken to her once,” I told Mercy, but it will never happen again. Never again shall that woman hear the sound of my voice. “

I wrote to my mother.

“I do not doubt that Mercy has told you of what happened on New Year’s Day. I trust you will be satisfied. You may be sure that I will always sacrifice my personal prejudices as long as nothing is asked of me which goes against my honour.”

I had never written to my mother in that tone before. I was growing up.

Of course the whole Court was laughing at the affair. People passing each other on the great staircase would whisper : II y a bien du monde aujowd’hm a Versailles!’ Servants giggled about it in the bedrooms. It was the catch phrase of the moment.

But at least what they considered my inane remark in the salon had stopped them—temporarily—speculating about what went on in the bedchamber.

I was right when I said the du Barry would not be satisfied. She longed for friendship. I did not understand that she wanted to show me that she had no desire to exploit her victory and she hoped that I felt no rancour on account of my defeat. She was a woman of the people who by good fortune had become rich; her home was now a palace and she was grateful to fate which had placed her there. She I wanted to live on good terms with everyone, and to her I must have seemed like a silly little girl.

What could she do to placate me? Everyone knew that I loved diamonds.

Why not a trinket after which I hankered? The Court jeweller had been showing a pair of very fine diamond earrings round the Court—hoping that Madame du Barry would like them. They cost seven hundred thousand livres—a large sum, but they were truly exquisite. I had seen them and exclaimed with wonder at their perfection.

Madame du Barry sent a friend of hers to speak to me about the earrings—casually, of course. I admired them very much, she believed.

I said I thought they were the most beautiful earrings I had ever seen. Then came the hint. Madame du Barry was sure she could persuade the King to buy them for me.

I listened in blank silence and made no reply. The woman did not know what to do; then I told her haughtily that she had my permission to go.

My meaning was dear. I wanted no favours from the King’s mistress; and at our next meeting I looked through her as though she did not exist.

Madame du Barry shrugged her shoulders. She had had a few words and that was all that was necessary. If La Petite Rousse wanted to be a little fool, let her. Meanwhile everyone continued to remark that there were a great many people at Versailles that day.

Greetings from Paris

Madame, I hope Monsieur Ie Dauphin will not be offended, but down there are two hundred thousand people who have fallen in love with you.

One advantage came out of that incident. I learned to be wary of the aunts. I began to see that that unfortunate affair might never have taken place but for them. Mercy grimly admitted that it might have taught me a valuable lesson, in which case it must not be completely deplored.

I was no longer the child I had been on my arrival. I had grown much taller and was no longer petite; my hair had darkened, which was an advantage, for there was a brownish tinge in the red so that the nickname Carrots was no longer so apt. The King quickly forgave me my intransigence over Madame du Barry, and my metamorphosis from child into woman pleased him. I should be falsely modest if I did not admit that I had ceased to be an attractive child and had become an even more attractive woman. I do not think I was beautiful, though. The high forehead which had caused such concern was still there, so were the uneven slightly prominent teeth—but I was able to give an impression of beauty without effort, so that when I entered a room all eyes were on me. My complexion was, I know, very clear”. and without blemish; my long neck and sloping shoulders; were graceful.

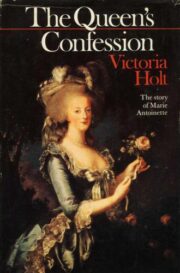

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.