But life was too amusing nowadays for seriousness. Mercy was writing to my mother that my only real fault was my extreme love of pleasure.

I certainly loved it and sought it everywhere.

But I could be thoughtful; and provided I was made aware of the sufferings of poor people, I could be very sympathetic, more so than most people around me.

I often embarrassed Madame de Noailles by this tendency, and on one occasion when I was with the hunt in Fontainebleau Forest I committed a breach of etiquette for which she found it difficult to reprove me.

They were hunting the stag, and because I was not allowed to ride a horse I had to follow in my calash. A peasant had apparently come out of his cottage at the moment when the terrified stag was passing. He was in its way and the poor creature gored him badly. The man lay by the roadside while the hunt swept by; but when I saw him I insisted on stopping to see how badly hurt he was.

His wife had come out of the cottage and was standing over him wringing her bands; on either side of her were two crying children.

We will carry him into the cottage and see how badly hurt he is,” I said, ‘and I will send a doctor to tend to him.” I commanded my male attendants to carry the man into his home, and there I was shocked by the sight of that humble home. Remembering the splendour of my gilded apartments at Versailles, I experienced a sense of guilt and wanted to show these people that I really cared what became of them. I saw that the wound was not deep, so I bandaged it myself, and leaving money I assured the wife that I would send a doctor to make sure that her husband recovered.

The wife had realised who I was and she was looking at me with something like adoration. When I left she knelt at my feet and kissed the hem of my gown. I was deeply moved.

I was more thoughtful than usual.

“The dear, dear people,” I kept saying to myself; and when I was next with my husband I told him of the incident and described the poverty of that cottage. He listened intently.

“I am glad,” he said with a rare emotion, ‘that you think as I do. When I am King of this country I want to do all I can for the people. I want to follow in the footsteps of my ancestor Henri Quatre. “

I wish to help you,” I told him earnestly.

“Balls, pageants … they are an unworthy extravagance.

I was silent. Why, I wondered, could one not be born good and gay?

My pity for the poor was like everything else about me— superficial. But when hardship was thrust under my nose I can say that I cared deeply.

It was the same when I asked one of my servants to move a piece of furniture and the poor old man in doing so fell and hurt himself. He fainted and I called to my attendants to come and help me.

We will send for some of his fellow servants, Madame,” I was told.

But I said no. I myself would see that he was adequately tended because it was in my service that he had hurt himself. So I insisted that they put him on a couch, I sent for water and I myself bathed his wounds.

When he opened his eyes and saw me on my knees beside him, his eyes filled with tears.

“Madame la Dauphine …” he whispered in an incredulous wonder, and he looked at me as though I were some divine being.

Madame de Noailles might tell me that it was not etiquette for a Dauphine to tend a servant, but I snapped my fingers at her; I knew that if I encountered similar incidents like those of the injured servant and peasant I should behave exactly as I had before. My actions were natural, and because I invariably acted without thinking, at least I had that virtue.

These incidents were talked of and doubtless magnified; and when I appeared in public the people cheered me more wildly than ever. They built up an image which I-could never live up to. I was young and beautiful, and in spite of the reports of my frivolity, I was good and kind; I cared for the people as no one had cared since the days of Henri Quatre, who had said: “Every peasant should have a chicken in his pot every Sunday.” I was of the same opinion. And my husband was a good man too. Together we would bring back the good days to France. All they had to do was wait for the old scoundrel to die and a new era would begin.

They began to speak of my husband as Louis Ie Desire.

We could not help feeling inspired by this. We wanted to be a good King and Queen when our time came. We remembered though, that we were failing in our first duty to provide heirs. Louis, I knew, was thinking of the scalpel which might free him from his affliction. But would it? Was it absolutely sure? And if it failed . There was another of those shameful periods of experiments of which I prefer not to think. Poor Louis, he was weighed down by his sense of responsibility; he was depressed by his inadequacy and deeply aware of his obligations. Sometimes I saw him at the anvil working in what seemed like a frenzy to tire himself out so that when he went to bed he would immediately fall into a heavy sleep.

We wanted to be good; but so much was against us . not only circumstances. We were surrounded by enemies.

I never failed to be astonished when I discovered that someone hated me.

My most careless conversation was commented on and misconstrued. The aunts watched me maliciously, although Victoire did so a little sadly.

She really believed that they could help and that in flouting Adelaide over the du Barry incident I had made a great mistake. Madame du Barry might have been helpful, but my attitude to her made her shrug her shoulders and ignore me.

She had her own troubles, and I believe during those first months of 1774 was a most uneasy woman.

There had been a paragraph in the Almanach de Liege an annual production special ising in foretelling the future which said: “In April a great Lady who is fortune’s favourite will play her last re1e.”

Everyone was talking about this and saying that it referred to Madame du Barry. There was only one way in which she could lose her position and that would be through the death of the King.

Those early months of that year were uneasy ones of mingling apprehension and the most abandoned gaiety. I attended all the Opera balls possible and I thought now and then of the handsome Swede who had made such an impression and wondered if I should see him again and what our encounter would be like if I did. But I did not see him.

I discovered a new enemy in the Comtesse de Marsan, governess to Clothilde and Elisabeth, who was a friend of my older antagonist,

Louis’s tutor the Due de Vauguyon. He had disliked me more than ever since I had caught him listening at doors; and when Vermond criticised Madame de Marsan’s guardianship of the Princesses I was blamed for this.

Some of my women repeated Madame de Marsan’s comments to me, thinking I should be warned.

“Someone said yesterday, Madame, that you carried your self more gracefully than anyone at court, and Madame de Marsan retorted that you had the walk of a courtesan.”

“Poor Madame de Marsan!” I cried.

“She waddles like a duck!”

Everyone laughed heartily, but there would be someone who would carry that to Madame de Marsan just as there was someone to carry her disparagements of myself to me.

My animation was praised.

“She likes to give the appearance of knowing everything,” was Madame de Marsan’s comment

When I favoured a new style of hairdressing wearing my hair in curls about my shoulders, which I know was most becoming, it reminded Madame de Marsan of a ‘bacchanal. ” My spontaneous laughter was ‘affected,” the manner in which I looked at men ‘coquettish. “

I could see that whatever I did would arouse the criticism of people such as the Comtesse, so what was the use of trying to please them?

There was only one course open to me to be myself.

Change was in the air.

We were staging scenes from Moliere and when we were thus engaged my brothers-and sisters-in-law were the characters they were trying to portray, which was often a great deal more comfortable than being themselves. My husband loved these theatricals; it suited him absolutely to be the audience, and whenever we did catch him sleeping he would retort that audiences often slept through plays and when this was the case actors should blame themselves, not the audience. But often he laughed and applauded; and there was no doubt that we were really all happier together when we were playing.

We felt the need to be even more careful. Knowing that Madame de Marsan was so critical, having learned that the aunts were aware of every false step I made, conscious all the time of the ever-watchful eyes of Madame L”Etiquette, I was sure that if it were discovered that we were aping players there would be an outcry of indignation and worst of all our pleasure would be forbidden. Knowing this we seemed to enjoy it all the more.

Monsieur Campan and his son were great acquisitions to our little company. Campan Pfere could play a part, procure our costumes and act as prompter all at once, because he could learn parts so easily that he invariably knew them all.

We had set up the stage and were preparing ourselves. The elder Monsieur Campan was dressed as Crispin, and very fine he looked in his costume. The meticulous man had made sure that it was exact in detail and he looked the part to perfection with his brilliantly rouged cheeks and his rakish wig.

The room which served as a theatre was rarely used-which was why he had chosen it—but there was a private staircase leading from it down to my apartments; and when I remembered that I had left in my apartments a cloak I should need, I asked Monsieur Campan to go down by the private staircase and get it for me.

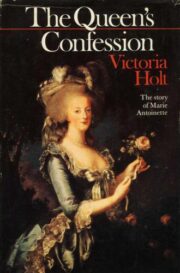

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.