I had not thought that there would be anyone in my apartments at this hour, but a man-servant had come on some errand and hearing a movement on the stairs he came to see who was there.

In the semi-darkness the strange figure from another age loomed before him on the dim staircase and naturally he thought he was confronted by a ghost. He screamed and fell backwards tumbling down the rest of the stairs.

Monsieur Campan rushed to him, and by this time, hearing the commotion, we all hurried down the staircase to see what was happening. The servant lay on the floor, fortunately unhurt, but white and trembling. He stared at us all—and I am sure we must have presented a strange sight. However,

Monsieur Campan, with his usual goodness, said that there was nothing to be done but explain the situation to the man.

“We are playing at theatricals,” he told him.

“We are not ghosts. Look at me. You will recognise me … and Madame la Dauphine …”

“You know me,” I said.

“See … we are only playacting.

“Yes, Madame,” he stammered.

“Madame,” said the wise Campan, “we must insist on his silence.”

I nodded and Monsieur Campan told the man that he must say nothing of what he had seen.

We were assured that secrecy would be kept, but the man went away looking dazed and we went back to our ‘stage,” but somehow the heart had gone out of our performance. We talked of the incident instead of continuing with the performance, and Monsieur Campan was very grave.

It was possible that the man would not be able to refrain from mentioning to one or two people what he had seen. We should be watched. All sorts of constructions would be put on our innocent game; we should be accused of orgies; and how easy it would be to attach to our theatrical ventures all sorts of sinister implications. Wise Monsieur Campan-thinking of me and no doubt knowing far more of the evil things which were said of me than I ever could—was of the opinion that we should stop our play. My husband agreed with him, and that was the end of our theatricals.

Without this to amuse me I turned to other pleasures. My old clavichord teacher, Gluck, had arrived in Paris some time before, and my mother had written to me urging me to help him make a success in Paris. I was delighted to do this, because I secretly believed that our German musicians excelled the French, yet in Paris I always had to listen to French opera. I naturally had a warm feeling for Mozart; and I was determined to do all I could for Gluck. In fact the Paris Academy had rejected his opera Iphigenia, but Mercy had prevailed upon them to rescind their decision.

On the night when the opera was performed I made a state occasion of it by begging my husband to accompany me. With us came Provence and his wife and a few friends among whom was my dear Princesse de Lamballe. It was a triumph. The people cheered me and I showed them how pleased I was to be among them. And at the end of the opera the curtain calls for Gluck went on for ten minutes.

Mercy was very pleased about this. He showed me what he was writing to my mother.

“I see approaching the time when the great destiny of the Archduchess will be fulfilled.”

I was inclined to preen myself, but Mercy would not have that.

He said: “The King is growing old. Have you noticed how his health has deteriorated during these last weeks?”

I replied that I thought he seemed a little tired.

He then put on his most confidential manner, which I was always intended to understand meant that what took place between us was of the utmost secrecy and should not be mentioned to anyone.

“If it should so happen … soon … that the Dauphin were called upon to nile, he would not be strong enough to do so by himself. If you did not govern him he would be governed by others. You should understand this. You should realise the influence you could wield.”

“II But I know nothing of affairs of state!”

“Alas, that is too true. You are afraid of them. You allow yourself to be passive and dependent.”

“I am sure I could never understand what was expected of me.”

“There would be those to guide you. You should team to know and appreciate your strength.”

During Lent the Abbe de Beauvais preached a sermon which was soon to be discussed through Versailles and I doubted not in every tavern in Paris. There seemed to be a feeling that the King’s days were coming to an end and it was almost as though the country were willing him to

die. Surely the Abbe would not have dared preach such a sermon as he did if the King had been well. I had discovered that for all his cynicism and sensuality my grandfather was an extremely pious man, by which I mean that he believed wholeheartedly in hell for the sinful unrepentant. He had led a life of such debauchery as few monarchs before him even French monarchs and he believed that if he did not obtain absolution of his sins he would surely go to hell.

Therefore he was uneasy. He wanted to repent but not too soon, for Madame du Barry was the one comfort in his old age.

The Abbe therefore dared preach against the ways of Court and of the King in particular. He likened him to the aged King Solomon, satiated by his excesses and searching for new sensations in the arms of harlots.

Louis tried to pretend that the sermon was really preached against certain members of his Court such as the Due de Richelieu, notorious as one of the biggest rakes of his day or anyone else’s.

Ha,” said Louis, ‘the preacher has thrown some stones into your garden, my friend.”

“Alas, Sire,” was sly Richelieu’s retort, ‘that on the way so many should have tumbled into Your Majesty’s park Louis could only smile grimly at such a retort; but he was seriously disturbed. He sought a way to silence the outspoken Abbe in the only way he could presenting him with a bishopric. This the Abbe accepted with pleasure but went on thundering out his warnings. He even went so far as to compare the luxury of Versailles with the lives of the peasants and the poor of Paris.

“Yet forty days and Nineveh shall be destroyed.”

Death seemed to be in the air. My charming grandfather changed visibly. He had become much fatter since my arrival yet he was more wrinkled; but the charm remained. I remember how shaken he was once at a whist party. One of his oldest friends, the Marquis de Chauvelin, was playing at one of the tables and, the game having ended, he rose and went to chat with a lady at one of the other tables. Quite suddenly his face was distorted; he gripped his chest, and then . he was lying on the floor.

My grandfather rose; I could see that he was trying to speak, but no words came.

Someone said: “He is dead. Sire.”

“My old friend,” murmured the King; and he left the apartment and went straight to his bedchamber. Madame du Barry went with him; she was the only one who could comfort him; and yet I knew that he was afraid to have her with him for fear he should die suddenly as his friend the Marquis had—with all his sins upon him.

Poor Grandfather! I longed to comfort him. But what could I do? I represented youth—and by its very nature that could only remind him of his own age.

It was almost as though fate were laughing at him. The Abbe de la Ville, whom he had recently promoted, came to thank him for his advancement. He was admitted to the King’s presence, but no sooner had he begun his speech of gratitude than he had a stroke and fell dead right at the King’s feet.

It was more than the King could bear. He shut himself in his apartments, sent for his confessor; and Madame du Barry was very worried.

Adelaide was delighted. When my husband and I visited her, she talked of the evil life the King had led and that ii he were to make sure of his place in Heaven he had better send that putain packing without delay. She was as militant as a general and her sisters were her obedient captains.

I have told him again and again,” she declared.

“The time is running out. I have sent a messenger to Louise to ask her to redouble her prayers. It would break my heart if when I reached Heaven it was to find my beloved father—the King of France—locked out.”

One day soon after the death of the Abbe de la Ville, when the King was riding, he met a funeral procession and stopped it. Who was dead, he wanted to know. It was not an old person this time, but a young girl of sixteen—which seemed equally ominous.

Death could strike at any time, and he was in his middle sixties.

As soon as Easter was over, Madame du Barry suggested that he and she should go and live quietly at the Trianon for a few weeks. The gardens were beautiful, for spring had come and it was a time to banish gloomy thought and think of life, not death.

She could always make him laugh; so he went with her. He went out hunting but felt extremely unwell. Madame du Barry, however, had prepared remedies for him and she kept declaring that all he needed was rest and her company.

The day after he had left I was in my apartment having my lessons on the harp when the Dauphin came in, looking very grave.

He sat down heavily and I signed to my music-master and the attendants to leave us.

“The King is ill,” he said.

Very ill? “

They do not tell us. “

He is at the Trianon,” I said.

“I shall go and see him at once. I will nurse him. He will soon be well again.”

My husband looked at me, smiling sadly.

“No,” he said, we cannot go unless he sends for us. We must wait for his orders to attend him. “

“Briquette!” I murmured.

“Our dearest grandfather is ill and we must wait on etiquette.”

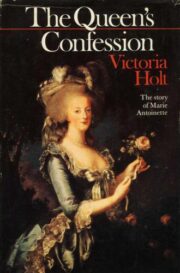

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.