“La Martiniere is going over,” my husband told me.

I nodded. La Martiniere was the chief of the King’s doctors.

“There is nothing we can do but wait,” said my husband.

“You are very worried, Louis.”

“I feel as though the universe were falling on me,” he said.

When La Martiniere saw the King he was grave, and in spite of Madame du Barry’s protestations insisted that he be brought back to Versailles. This in itself was significant and we all knew it. For if the King’s malady had been slight he would have been allowed to stay at the Trianon to recover. But no, he must be brought back to Versailles because etiquette demanded that the Kings of France should die in their state bedrooms at Versailles.

They brought him the short distance to the palace and I saw him emerge from his carriage for I was watching from a window. He was wrapped in a heavy cloak and he looked like a different person; he was shivering yet there was an unhealthy flush on his face.

Madame Adelaide came hurrying out to the carriage and walked beside him giving orders. He was to wait in her apartments while his bedchamber was made ready—for so urgent had La Martiniere declared was the need to return to Versailles that this was not yet done.

When he was in his room we were all summoned there, and I had to fight hard to stop myself bursting into tears. It was so tragic to see him with the strange look in his eyes, and when I kissed his hand he did not smile or seem to care. It was as though a stranger lay there. I knew he was not sincere, yet in my way I had loved him and I could not bear to see him thus.

He wanted none of us; only when Madame du Barry came to the bedside did he look a little more like himself.

She said: “You’d like me to stay, France!” which was very disrespectful, but he smiled and nodded; so we left her with him.

That day was like a dream. I could settle to nothing. Louis stayed with me. He said it was better we should be together.

I was apprehensive; and he continued to look as though the universe was about to fall upon him.

Five surgeons, six physicians and three apothecaries were in attendance on the King. They argued together as to the nature of his complaint, whether two—or three—veins should be tapped. The news was all over Paris. The King is ill. He has been taken from the Trianon to Versailles. Considering the life he has led, his body must indeed be worn out;

Louis and I were together all the time, waiting for a summons. He seemed as though he were afraid to leave me.

I was praying silently that dear Grandfather would soon be well; I know Louis was too.

In the Oeil de Boeuf, that huge anteroom which separated the King’s bedchamber from the hall and which was so called because of its bull’s-eye window, the crowds were assembled. I hoped the King did not know, for if he did he would know too that they believed he was dying.

There was a subtle difference in the attitude of those around us towards myself and my husband. We were approached more cautiously, more respectfully. I wanted to cry out:

“Do not treat us differently. Papa is not dead yet.”

News came from the sickroom. The King had been cupped but this had brought no relief from his pain.

The terrible suspense continued through the next day. Madame du Barry was still in attendance on the King but my husband and I had not been sent for. The aunts, however, had decided that they would save their father;

and they were certainly not going to allow him to remain in the care of the putain. Adelaide led them into the sickroom although the doctors tried to keep them out.

What actually happened when they entered the sickroom was so dramatic that soon the whole Court was talking of it.

Adelaide had marched to the bed, her sisters a few paces behind her, just as one of the doctors was holding a glass of water to the King’s lips.

The doctor gasped and cried, “Hold the candles nearer. The King cannot see the glass.”

Then those about the bed saw what had startled the doctor. The King’s face was covered in red spots.

The King was suffering from smallpox. There was a feeling of relief because at least everyone knew now what ailed him and the right cures could be applied; but when Bordeu, the doctor whom Madame du Barry had brought in and in whom she had great faith, heard how pleased everyone was, he remarked cynically that it must be because they hoped to inherit something from him.

“Smallpox,” he added, ‘for a man of sixty-four and with the King’s constitution is indeed a terrifying disease. “

The aunts were told that they should leave the sickroom immediately, but Adelaide drew herself up to her full height and looking her most regal demanded of the doctors: “Do you presume to order me from my father’s bedchamber? Take care that I shall not dismiss you. We remain here. My father needs nurses and who should look after him but his own daughters?”

There was no dislodging them and they remained—actually sharing with Madame du Barry the task of looking after him, although they contrived not to be in the apartment when she was there. I could not but admire them all. They worked to save his life, facing terrible danger; and they were as devoted as any nurses could be. I have never forgotten the bravery of my Aunt Adelaide at that time—Victoire and Sophie too, of course: but they automatically obeyed then-sister. My husband and I were not allowed to go near the sickroom. We had become too important.

The days seemed endless, like a vague dream. Each morning we arose wondering what change in our lives the day would bring. The fact that the King was suffering from smallpox could not be kept from him. He demanded a mirror to be brought to him and when he looked into it he groaned with horror. Then he was immediately calm.

“At my age,” he said, ‘one does not recover from that disease. I must set my affairs in order. ” Madame du Barry was at his bedside but he shook his head sadly at her. It grieved him more than anything to part with her, but she must leave him … for her own sake and for his.

She left reluctantly. Poor Madame du Barry! The man who had stood between her and her enemies was fast losing his strength. The Ring kept asking for her after she had left and was very desolate without her. I felt differently towards her from that time. I wished I had been kinder to her and spoken to her now and then. How sad she must be feeling now, and her sorrow would be mingled with fear, for what would become of her when her protector was gone?

He must have loved her dearly, for while his priests were urging him to confess he kept putting it off, for once he had confessed he would have to say a last goodbye to her, for only thus could he receive remission of his sins; and all the time he must have been hoping that he would recover and be able to send for her to come back to him.

But in the early morning of the 7th of May the King’s condition worsened so much that he decided to send for a priest.

From my windows I could see that the people of Paris had come to Versailles in their thousands. They wanted to be on the spot at the moment when the King died. I turned shuddering from the window; to me it seemed such a horrible sight, for sellers of food and wine and ballads were camping in the gardens and it was more like a holiday than a sacred occasion. The Parisians were too realistic to pretend that they were mourning; they were rejoicing because the old reign was passing and they hoped for so much from the new.

In the King’s apartments the Abbe Maudoux waited upon him; I heard the remark passed that it was the first time for over thirty years when he had been installed as the King’s confessor that he had been called to duty. In all that time the King had had no time for confession. How, it was asked, will Louis XV ever be able to recount all his sins in time?

I wished that I could have been with my grandfather then. I should have liked to tell him how much his kindness had meant to me. I would have told him that I should never forget our first meeting in Fontainebleau when he had behaved so charmingly to a frightened little girl. Surely such kindness would be in his favour; and although he had lived scandalously, none of those who had shared his debauchery had been forced to do so, and many had been fond of him. Madame du Barry had shown by her conduct not merely that he was her protector but that she loved him. She had left him now, not because she feared his disease but in order f to save his soul.

News was brought to our apartment of what was happening in the chamber of death. I heard that when the Cardinal de la Roche Aymon entered in full canonicals bringing with him the Host, my grandfather took his nightcap from his head and tried in vain to kneel in the bed, for he said:

“If my God deigns to honour such a sinner as I am with a visit, I must receive him with respect.”

Poor Grandfather, who had been supreme all his life a King from five years old now would be denuded of all his worldly glory and forced to face one who was a greater King than he could ever have been.

But the high dignitaries of the Church would not allow absolution merely in return for a few muttered words. This was no ordinary sinner; this was a King who had openly defied the laws of the Church and he must make public avowal of his sins; only thus could they be forgiven.

There was a ceremony in which we must all take part that his soul might be saved. We formed a procession, led by the Dauphin and myself with Provence, Artois, and their wives following us. We all carried lighted candles and followed the Archbishop from the chapel to the death chamber, lighted tapers in our hands, solemn expressions on our faces, and in my heart, and that of the Dauphin at least, a sorrow and a great dread.

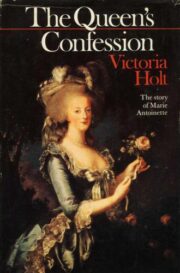

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.