“A most able man. Why, when he was twenty-four he controlled the King’s house hold as well as the Admiralty.”

“But he lost his posts.”

“Why? … why? Because he was no friend of Pompadour. That was our father’s mistake. However able a man, if one of his women did not care for him it was the end.”

She went on enumerating the merits of Maurepas, and eventually my husband decided to destroy the letter he had written to Machault and instead wrote to Maurepas. I was there when he wrote the letter which seems to convey so much of his feeling at that time.

“Amidst the natural grief which overwhelms me and which I share with the entire kingdom, I have great duties to fulfill. I am the King; the word speaks of many responsibilities. Alas, I am only twenty [my husband was not even that; he had three months to wait for his twentieth birth day] and I have not the necessary experience. I have been unable to work with the ministers, as they were with the late King during his illness. My certainty of your honesty and knowledge impels me to ask you to help me. You will please me if you come here as soon as possible.”

No King of France ever ascended the throne with a greater desire for self-abnegation than my husband.

Having secured the appointment of Maurepas the aunts were triumphant, believing they were going to be the power behind the throne. They watched me suspiciously and I knew that when I was not present they warned the King against allowing his frivolous little wife to meddle.

He was so good, he immediately had two hundred thousand francs distributed to the poor; he was greatly concerned about the licentiousness of the Court and determined to abolish it. He asked Monsieur de Maurepas how he could set about bringing a state of morality to a court where morals had been lax for so long.

“There is but one way. Sire,” was Maurepas’s answer.

“It is one Your Majesty must take to set a good example. In most countries—and in particular in France—where the Sovereign leads, the people will follow.”

My husband looked at me and smiled, very serenely, very confidently.

He would never take a mistress. He loved me; and if he could only become a normal man, we would have children and ours would be the perfect union.

But there was so much to think of at that time that that uneasy subject was forgotten.

Louis was kind. He could not even be cruel to Madame du Barry.

“Let her be dismissed from the Court,” he said.

“That should suffice. She shall go to a convent for a while until it is decided to what place she may be banished.”

It was lenient, but Louis had no wish to punish. Nor had I. I thought of that time When I had been forced to say those silly words to her.

How angry I had been at the time, but now it was all forgotten; and I could only remember how she had stayed with the King when he was so ill and she was in danger of catching the dreaded disease. Let her be banished. That was enough.

Louis quickly grasped that the country’s finances were in disorder, and determined on household economies. I was beside him and declared that I too would econo mise I gave up my droit de ceinture, a sum of money which was given by the State for my private purse which hung on my girdles.

“I have no need of this,” I said.

“Girdles are no longer worn.”

This remark was repeated in the Court and in the streets of Paris.

Paris and the whole country were pleased with us. I was their enchanting little Queen; my husband was Louis Ie Desire, and one morning when the traders started their early morning trek to Les Halles it was noticed that during the night someone had written “Resurrexit* on the statue of Henri Quatre which had been erected on the Font Neuf.

When my husband heard of this his eyes shone with pleasure and determination. In every Frenchman’s opinion Henri Quatre was the greatest King France had ever had, the King who had cared for the people as no other monarch had before or since.

Now they were saying that in Louis Ie Desire this great monarch was born again.

At Choisy it was easy to forget those last nightmare days at Versailles. I was Queen of France; in his way my husband loved me; everyone was eager to pay me homage. Why had I been apprehensive?

I knew that any mother would be anxiously watching events. No doubt it had already been reported to her how I had conducted myself during the King’s illness and death; but I myself would write to her.

With the new flush of triumph on me I wrote—rather arrogantly (I excuse myself for I was freshly savouring the flattery which is paid to a Queen):

“Although God chose that I should be born to high rank, I marvel at the design of Fate which has chosen me, the youngest of your daughters, to be Queen of the finest Kingdom in Europe.”

My husband came in while I was writing this letter and I called to him to see what I had written. He looked over my shoulder smiling. He knew of my difficult penmanship and said that was very good.

You should add something to the letter,” I told him.

“It would please her.”

“I should not know what to say to her.”

“Then I will tell you.” I thrust the pen into his hand, and jumping up pushed him into my chair. He chuckled under his breath, half embarrassed, half delighted by my spontaneous gestures as he so often was.

“Say this: ” I am very pleased, my. dear Mother, to have the

opportunity to offer you proof of my affection and regard. It would give me great satisfaction to have the benefit of your counsel at such a time which is so full of difficulties for us both. “

He wrote rapidly and looked at me expectantly.

“You are so much cleverer than I with a pen,” I retorted.

“Surely you can finish it.” He continued to laugh at me. Then as though determined to impress me with his cleverness he began to write rapidly:

. but I shall do my best to satisfy you and by so doing show you the affection and gratitude I feel towards you for giving me your daughter with whom I could not be more satisfied. “

“So,” I said, ‘you are pleased with me. Thank you. Sire. ” I dropped a deep curtsy. Then I was on my feet, snatching the pen from him. I wrote below his message:

“The King wished to add his few words before allowing this letter to go to you. Dear Mother, you will see by the compliment he pays me that he is certainly fond of me, but that he does not spoil me with high-flown phrases.” He looked puzzled and half ashamed.

What would you wish me to say? “

I laughed, snatching the letter from him and sealed it myself.

“Nothing that you have not already said,” I replied.

“Indeed, Sire, Fate has given me the King of France, with whom I could not be more satisfied.”

This was typical of our relationship at this time. He was satisfied with me, although he did not wish me to meddle in politics. He was the most faithful husband at Court; but I was not sure at this time whether this was due to his devotion to me or to his affliction.

One of the most anxious women in Europe was my mother. She was so wise. She deplored the fact that the King was dead. If he had lived another ten or even five years we should have had time to prepare ourselves. As it was, we were two children. My husband had never been taught how to rule; I would never learn. That was the position as she saw it. And how right she was I I often marvel that while all those people dose at hand were dreaming of the ideal state which they landed two inexperienced young people could miraculously turn the country into, my mother from so far away could see the picture so clearly.

Her answer to my thoughtless letter—the one to which I had made my husband add his comments was:

“I do not compliment you on your new dignity. A high price has been paid for this, and you will pay still higher unless you go on living quietly and innocently in the manner in which you have lived since your arrival in France. You have had the guidance of one who was as a father to you and it is due to his kindness that you have been able to win the approval of the people which is now yours. This is good, but you must learn how to keep that approval and use it for the good of the King your husband, and the country of which you are Queen. You are both so young, and the burden which has been placed on your shoulders is very heavy. I am distressed that this should be.”

She was pleased that my husband had joined with me in writing to her and hoped that we should both do all we could to maintain friendly relations between France and Austria.

She was extremely worried about me—my frivolity, my dissipation (by which she and Mercy meant my preoccupation with matters which were of small importance), my love of dancing, and gossip, my disrespect for etiquette, my impulsiveness. All qualities, my mother pointed out, to be deplored in a Dauphine but not even to be tolerated in a Queen.

“You must learn to be interested in serious matters,” she wrote.

“This will be useful if the King should wish to discuss state business with you. You should be very careful not to be extravagant; nor to lead the King to this. At the moment the people love you. You must preserve this state of affairs. You have both been fortunate beyond my hopes; you must continue in the love of your people. This will make you and them happy. “

I replied dutifully that I realised the importance of my position. I confessed my frivolity. I swore that I would be a credit to my mother.

I wrote and told her of all the homage, all the ceremonies, how eager everyone was to please me. She wrote back, sometimes tender, often scolding; but her comment was: “I fancy her good days are over.”

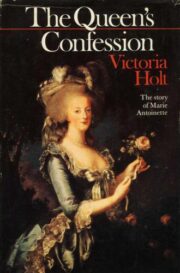

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.