But at the time, I was flushed with triumph. I had had Aiguillon dismissed; now I would bring back my dear friend Monsieur de Choiseul.

“Poor Monsieur de Choiseul,” I said one day to my husband when we were alone in our apartment, ‘he is sad at Chanteloup. He longs to be back at Court. “

“I never liked him,” my husband replied.

“Your grandfather liked him …”

“And in time dismissed him.”

“That was due to du Barry. She brought that about. Your Majesty would not be influenced by a woman like thati’ ” I shall-always remember what he said to me one day.

“Monseigneur,” he said, “I may one day have the misfortune to be your subject, but I shall never be your servant” “

“We all say things at times which we do not mean. I am sure I do.”

He smiled at me tenderly.

“I am sure you do too,” he said.

I put my arms about his neck. He flushed slightly. He liked these attentions but they made him uncomfortable. I believe they brought back memories of those embarrassing embraces in the bedchamber.

“Louis,” I said, “I want you to allow me to invite Monsieur de Choiseul to return to Court. Can you deny me such a little thing?”

“You know that I find it difficult to deny you anything, but …”

“I knew you would not disappoint me.” I released him, thinking: I’ve won.

I lost no time in making it clear to Monsieur de Choiseul that the King had given him permission to return to Court, and Monsieur de Choiseul lost no time in coming.

He was full of hope, and when I saw him, although he had grown much older since our last meeting, I still thought him a fascinating man (for with his odd pug face he had never been handsome).

I was to learn something about my husband. He was not to be led. He was fond of me; he was proud of me; but he really believed that women must be kept out of politics and he was not going to allow even me to interfere.

He looked coolly at Choiseui and said: “You have put on weight since we last met. Monsieur Ie Due; and you have grown balder.”

Then he turned away, leaving the Due disconsolate. But there was nothing he could do; the King had turned away and dismissed him.

It was significant. I was not going to influence my husband. That would be a matter for his ministers.

I was sorry but for Monsieur de Choiseui, not for myself. I was ready to give up my dreams of power; nothing as serious as politics could hold my attention for long, and Mercy would have to tell my mother that the King was a man who would go his own way and that they must not expect me to meddle.

Mercy told me that my mother was not sorry Monsieur de Choiseui had not been taken back. I had asked the King to receive an ex-minister and the King had shown his respect for me doing so. That pleased her.

As for Monsieur de Choiseui, she did not think his character was such as would allow him to be of much help to the French nation at this stage of its history. At the same time, I had done well to bring about the dismissal of the Due d’Aiguillon.

It was always pleasant to have praise from my mother; but I could not enjoy her approval for long.

The Grim Rehearsal

“If the price of bread does not go down and the Ministry is not changed, we will set fire to the four corners of the Chateau of Versailles’

“If the price does not go down we will exterminate the King and the entire race of Bourbons’

Soon after we became King and Queen, Louis gave me the gift which brought more pleasure to me than anything else I ever possessed.

He came into our bedchamber one day and said rather sheepishly that it was the custom of each King of France to present his Queen on her accession to the throne with a residence which should be all her own to do with as she would. He had decided to present me with Le Petit Trianon.

Le Petit Trianon! That enchanting little house! Oh, it was delightful.

I loved it. Nothing, I declared, could have made me happier.

He stood smiling at me while I threw my aims about his neck and hugged him.

“It is very small.”

It’s a doll’s house!

“I cried.

“Hardly grand enough for the Queen of France, perhaps.”

“It’s beautiful!” I cried.

“I wouldn’t exchange it for any chateau in the world.”

He began to chuckle quietly as he often did at my wild enthusiasm.

“So it’s all mine!” I cried.

“I may do as I like there? There I can live like a simple peasant.

I’ll tell you one thing, Louis, there is one guest who will not be invited there. It is Etiquette. That may remain behind in Versailles.”

I summoned the Princesse de Lamballe and with some of my youngest ladies went to look at Le Petit Trianon without delay. It looked different from when I had glanced casually at it en passant. I suppose because it was entirely mine. I loved it because it was small a refuge, situated just far enough from the palace to be a retreat and not far enough for one to have to make a journey to reach it.

It was delightful a villa. This was how humbler people lived; and how often during the life of a Queen, with so many tiresome ceremonies to be performed, did one long to be humble. Little ClaremontTonnerre cried that it had been the mais on de plaisir of Louis XV the little love-nest where he and Madame du Barry had taken refuge from Versailles.

“That is all over,” I said firmly.

“Now it will be known as the refuge of Marie Antoinette. We will change it. We will make it entirely my house so that nothing remains of that woman.”

“Poor creature. Doubtless she would like to change Font aux Dames for the Trianon now.”

I frowned. I did not want to gloat over my enemies’ mis fortunes. I never did. I merely wanted to forget them.

There were eight rooms only, and we were all very amused by the odd contraption which was a kind of table and which could be made to rise from the basement to the dining-room. This had been constructed for the use of Louis XV, so that when he brought a mistress to the Petit Trianon who did not wish to be seen by servants, a meal could be prepared in the basement and sent up to the dining room without any servants appearing. We shrieked with laughter as the old thing creaked up and down.

The house was tastefully furnished. My grandfather would doubtless have seen to that. I did not think the furniture with its delicately-embroidered upholstery was the choice of du Barry.

“Oh, it is perfect perfect!” I cried running from room to room.

“What fun I shall have here!”

I ran to the windows and looked out on beautiful lawns and gardens. I could do so much here. I could refurnish it if I wished, although I liked the present furniture. There must be nothing overpoweringly splendid to remind me of Versailles. Here I would entertain my dearest friends and we should cease to be Queen and subjects.

I could not see Versailles from the windows, which was an added charm.

Here I could come when I wanted to forget the chateau and Court life.

I was delighted that my husband had given me this little house. How much more charming than Le Grand Trianon which Louis XIV had built for Madame de Maintenon. I could never have felt so pleased with that.

I could scarcely wait to get back to Versailles to tell my husband how enchanted I was with his gift

In February my brother Maximilian visited me. My mother had sent him on a tour of Europe in order to complete his education, so naturally be came to see me. He was eighteen, and as soon as I saw him I realised how my years in France had changed me. This was young Max who had sat with Caroline and me in the gardens of Schonbrunn and watched our elder brothers and sisters perform. He had always been chubby, but now he had grown fat; and he seemed awkward and decidedly inelegant.

I was rather ashamed of him, particularly now that, knowing the French so well, I could imagine what they were saying about him, although they received him so graciously. But graciousness was lost on Max; he didn’t recognise it; he didn’t see what mistakes he made, because he thought everyone who didn’t agree with him must be wrong. He was just like Joseph but without my eldest brother’s good sense.

Louis asked him to sup with us privately and behaved as though he were a brother, and I was pleased to ask questions about home and my mother. Yet the more I listened, the more I realised how far from the old life I had grown. It was five years since I had shivered naked in the Salon de

Remise on that sandbank in die Rhine. I felt I had become French, and when I looked at Max heavy, awkward, humourless I was not sorry.

It was inevitable that there should be gossip about my brother; all his little gaucheries were recorded and exaggerated. Through the Court they spoke of him as the Arch-Fool instead of the Archduke, and stories about him were circulated through the streets of Paris by my enemies.

Max was not only ignorant of French etiquette but deter mined not to bow to it; and because of this, a contretemps arose. As a visiting royalty it was his duty to call on the Princes of the Blood Royal and they awaited a call from him; but Max stubbornly said that as he was a visitor to Paris it was their duty to call on him first. Both were adamant, and a difficult situation was created, for none of them would give way, and consequently Max did not meet the Princes. Orleans, Conde and Conti declared this was a deliberate insult to the Royal House of France.

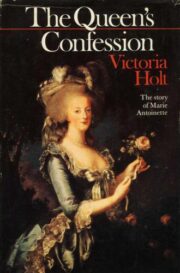

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.