When my brother-in-law Provence gave a banquet and a ball in honour of my brother, the three Princes of the Blood Royal made their excuses and left the city. It was a clear insult to my brother.

That in itself was bad enough, but when the Princes returned, very ostentatiously, to Paris, the people crowded into the streets to cheer them and murmur against Austrians.

When Orleans came to Court I reproached him.

“The King invited my brother to supper,” I said, ‘which you never did.”

“Madame,” replied Orleans haughtily, ‘until the Archduke called on me I could not invite him. “

“This eternal etiquette! It wearies me.”

How impulsively I spoke! That would be interpreted as: “She pokes fun at French customs; she would substitute those of Austria.” I must guard my tongue. I must think before I spoke.

“My brother is only in Paris for a short time,” I explained. There is so much for him to do. “

Orleans coldly inclined his head; and my husband, seeing him, expressed his annoyance by banishing Orleans, with Conde and Conti, from the Court for a week.

That was small consolation, for the Princes were constantly appearing in public and being cheered by the people as though they had done something very brave and commendable in refusing to be kind to my brother.

I was not sorry to see Max go. My sister Maria Amalia was causing a certain amount of scandal through her behaviour in Parma. This was discussed in Paris, and it was considered that I had somewhat disreputable relations.

But what can you expect of Austrians? ” people were asking each other.

After Max’s visit I don’t think the people of France were ever quite so fond of me as they had been before.

While I was occupied with the Trianon—and in fact I gave little serious thought to anything else at this time—a very grave situation had arisen in France.

I did not clearly understand it, but I knew that the King was very worried. He did not wish to speak to me of these anxieties, for my attempts to get him to reinstate Choiseui had strengthened him in his desire to keep me out of politics. He liked to see me happy with the Trianon, and that kept me busy.

As I saw it, what happened was this.

In August Louis had appointed Anne Robert Jacques Turgot as Comptroller-General of Finances. He was a very handsome man, about forty-seven, with abundant brown hair which hung to his shoulders; he had well-cut features and dear brown eyes. My husband was fond of him because there was a-similarity between them. They were both awkward in company. I once heard that when he was a child Turgot used to hide himself behind a screen when there were visitors at his home and only emerge after they had gone. He was always awkward and blushed easily; and this gaucherie rather naturally endeared him to my husband.

Louis was very pleased on the appointment and talked to me a little about Turgot, but I was too much immersed in my own affairs to listen for long; but I did gather that the finances of the country were, in my husband’s opinion, such as to cause grave concern, and that Turgot had what he called a three-point programme, which was:

No bankruptcy.

No increase in taxation.

No loans.

You see,” said my husband, ‘there is only one way to make possible Turgot’s programme. Complete economy to reduce expenses. We must save twenty millions a year and we must pay off our old debts ” Yes, of course,” I agreed, and I was thinking: Pale blue and pale cherry for the bedroom. My bedroom! A single bed where there will not be room for my husband…. Louis was looking apologetic.

“Turgot has told me that I must look to my own expenses and that my first duty is to the people. He said:

“Your Majesty must not enrich those he loves at the expense of the people.” And I agreed with him wholeheartedly. I am fortunate to have found such an able minister. “

“So fortunate,” I agreed. No stiff satin, I thought. No heavy brocade.

This is suitable for Versailles. But for my darling Trianon . soft silks in delicate shades.

“Are you listening?” he asked.

“Oh yes, Louis. I agree with you that. Monsieur Turgot is a very good man and we must econo mise We must think of the poor people.”

He smiled and said that he knew I would be beside him in all the reforms he intended to make because he knew that I cared about the people as much as he did.

I nodded. It was true. I did want them all to be happy and pleased with us.

I wrote to my mother that day:

“Monsieur Turgot is a very honest man, which is most essential for the finances.”

I realise now that it was one thing to have good intentions and another to carry them out. Monsieur Turgot was an honest man, but idealists are not always practical, and luck was against him, because the harvest that year was a bad one. He established internal free trade, but that could not keep the price of corn down, because of the shortage. Moreover, roads were bad and the grain could not be brought to Paris. Turgot met this situation by throwing on the market grain from the Royal Granaries, which had the effect of bringing down the price, but as soon as it was used up the price rose again and the people were more discontented than ever.

Then there was a distressing rumour that in various pans of the country people were starving, and there was murmuring against Turgot.

The news got worse. Riots broke out at Beauvais, Meaux, Saint-Denis, Poissy, Saint Gennain; and at Villers Cotterets a crowd collected and started to raid the markets. Boats on the Oise which were carrying grain to Paris were boarded and sacks of corn were split open. When the King heard, that the raiders had not stolen the precious grain but thrown it into the river he was very disturbed.

He said gravely: “It does not sound like hungry people, but those determined to make trouble.”

Turgot, who was suffering acutely from the gout and had to be carried to my husband’s apartments, was constantly there.

I had been at Le Trianon revelling in the paintings of Watteau which adorned the walls and deciding that I should not attempt to alter the carved and gilded panelling, and I returned to find my husband preparing to leave for the hunt. He had spent many hours in close consultation with Turgot and he told me that he wanted to get away for a while to think about the depressing situation. Then Turgot and Maurepas had left for Paris, for word had come to them that organised agitators were planning to lead raids on the markets there. My husband decided to take a short respite; in any case he could always think more easily in the saddle.

I was in my apartments when the King came bursting in on me.

“I had just left the Palace when I saw a mob,” he said.

“They are coming from Saint Gennain and are on their way to the Versailles market.”

I felt the blood rushing to my face. The mob . marching on Versailles. Old Maurepas and Turgot away in Paris and no one to send them away. No one, that was, but the King.

He looked pale but resolute.

“I find it hard to bear when the people are against us,” he said.

Then I thought of that moment when we had known we were King and Queen of France and how we had both cried out that we were too young, and I forgot the Trianon;

I forgot everything but the need to stand beside him, to support him, to will him to be strong. I took his hand and he pressed my fingers.

There is no time to be lost,” he said.

“Action, prompt action, is necessary.” Then the old look of self-doubt was in his face.

“The right action,” he added.

The Princes of Beauvau and de Poix were in the chateau and he sent for them poor substitutes for Maurepas and Turgot. He briefly explained the situation. He said: “I will send a message to Turgot, and then we shall have to act.”

I knew he was praying silently that the ac don he took would be the right one. And I prayed with him.

He sat down and wrote to Turgot:

Versailles is attacked. You can count on my firmness. I have ordered the guards to the market place. I am pleased with the precautions you have taken in Paris, but it is what could happen there that alarms me most. You are right to arrest the people of whom you speak, but when you have them remember I wish there to be no haste and many questions. I have just given orders what shall be done here, and for the markets and mills of the neighbourhood. ” I stayed with him, and I was gratified that that seemed to please him.

“What alarms me is,” he said, ‘that this should appear to be an organised riot. It is not the people. The situation is not as bad as that. There is nothing that we could not set co rights given time. But this is organised planned the people are being incited against us. Why? “

I thought of how the people had cheered me when I first went to Paris and Monsieur de Brissac had said two hundred thousand people had fallen in love with me; I thought of the people cheering us in the Bois de Boulogne.

“The people love us, Louis,” I said.

“We may have our enemies, but they are not the people.”

He nodded, and again I realised by the way he looked at me that he was glad I was there.

That was a terrible day. I could eat nothing; I felt faint and slightly sick. The waiting was terrible, and when I heard the sounds of shouting approaching the chateau I was almost relieved.

That was my first glimpse of an angry mob. There they were in the grounds of the chateau unkempt, in rags, bran dishing sticks and howling abuse. I stood a little way back from the window watching.

Someone threw something; I could see it on the balcony. It looked like mouldy bread.

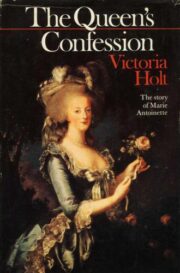

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.