I did not mention this. I contented myself with a lighthearted rejoinder that one must enjoy oneself while one was young.

“When I grow older I shall be more serious; then my frivolity will disappear.”

I was surprised that old Kaunitz understood my position far better than my mother or my brother. He wrote to Mercy:

“We are young yet, and I fear we shall be so for a very long time.”

This time was difficult for my husband too. The kingly bearing he displayed at the time of the guerre des farines seemed to have disappeared; be asserted himseu in odd ways. He liked to fight with his attendants, and often I would go to his apartments and see him wrestling on the floor. He always got the better of his opponents, for he was much stronger than they were; this must have given him the feeling of superiority he needed to feel.

He was the absolute antithesis of everything that I was. He did not complain of my extravagance, but he was so thrifty that he was almost mean; there was no subtlety about him. Sometimes he would fix one of his friends by his expression and walk towards him so that the poor man had to retreat until he was standing against a wall. Then Louis would find he had nothing to say and would laugh loudly and walk away.

His appetite was voracious. I have seen him eat for break fast a chicken and four cutlets, several slices of ham and six eggs all washed down with half a bottle of champagne. He worked at the forge which he had had installed on the top story and there he would hammer away and make boxes of iron, and keys. Locks were his passion. He had a work man up there named Gamain who treated him as though he were a fellow-worker and even jeered at his efforts, all of which Louis took in the utmost good humour, declaring that in the forge Gamain was a better man than he was.

At his coucher he was as impatient of etiquette as I was and would take his cordon bleu and throw it at the nearest man. Stripped to the waist he would scratch himself before the courtiers and when the noblest present tried to help him into his nightgown he would run round the room leaping over the furniture, forcing them to chase him which they did until they were out of breath. Then he would take pity on them and allow them to put on his nightgown. The nightgown on, and his breeches loosed, he would engage them in conversation, walking about the room with his breeches about his ankles so that he was obliged to shuffle.

It was the Due de Lauzan who made me realise how dangerously Louis and I had drifted apart. At a party at the house of the Princesse de Guemenee, Lauzan appeared in a very splendid uniform and on his helmet was the most magnificent heron’s plume. I thought it very beautiful and impulsively said so. The very next day a messenger came from the Princesse de Guemenee with the feather and a note from the Princesse which said that the Due de Lauzan had begged her to implore me to accept it.

I was embarrassed, but I knew that to return the feather would be to wound him deeply, and impulsively decided that I would wear the feather once and then lay it aside.

Monsieur Leonard used it for my head-dress, and when Lauzan saw it his eyes gleamed with pleasure.

The next day he presented himself at my apartment and begged an interview. Madame Campan was in attendance and I granted the interview as I should have done to anyone. He wished, he said, to speak to me privately if I would so honour him.

I glanced at Madame Campan; she knew the signal. She would go into the anteroom and leave the door open, because she knew that I was never alone with men.

When she had disappeared he threw himself on to his knees and began kissing my hands.

“I was overcome with joy,” he cried, ‘when I saw you wearing the aigrette. It was your answer the answer I longed for. You have made me the happiest man in the world. “

“Stop,” I said.

“Are you mad. Monsieur de Lauzan?”

He stumbled to his feet, the colour draining from his face. He said:

“Your Majesty was gracious enough to show me by our token …”

“You are dismissed,” I told him.

“But you …”

“Will you go. Monsieur de Lauzan? Immediately! … Madame Campan come here please!”

She was there as I knew she would be.

There was only one thing Lauzan could do. He bowed and retired.

I said to Madame Campan: “That man shall never again come within my doors.”

I was shaking with apprehension. I was both angry and alarmed. I knew that I was to blame in a way. I had behaved coquettishly; and I had been so foolish as to wear the plume. Why could not these people understand that I merely wanted to be amused I Lauzan never forgave me. His feelings for me were indeed strong and if he could not be my lover he could at least become my enemy. He was that—in the years when I so needed friends.

There were times when I longed to escape from the Court; and there was the Petit Trianon waiting to welcome me; but sometimes I felt as though I wanted to get far away;

I wanted to ride out in my calash and be alone—which was strange for me. Not that I was alone. There was ceremony even when I went riding informally in this way;

I must have my coachman and postilions.

We rode through villages and I looked out at the children at play—beautiful creatures whom I should have been so happy to call mine; as we rode along, suddenly one of these littles ones ran out of a cottage and almost under the horses’ hoofs. I cried out, the coachman pulled up sharply; the little boy lay sprawled in the road.

Is he hurt? ” I cried, leaning out.

The child began to scream wildly as one of the postilions picked him up.

He kicked furiously, and the postilion grinned.

“I cannot think much ails him. Your Majesty. But he’s frightened.”

“Bring him to me.”

He was brought. His clothes were ragged but not unclean;

he stopped crying as I took him, and looked up at me wonderingly. He had large blue eyes and light-coloured waving hair. He was like a little cherub.

“You are not hurt, darling,” I said.

“And there is nothing to fear.”

A woman had come out of the cottage; two children, older than the little boy, ran after her and I caught a glimpse of others.

“The boy …” began the woman; and she looked at me in astonishment.

I was not sure if she knew who I was.

“Jacques, what are you doing?”

The little boy on my lap turned his head from her and nestled closer to me. That decided me. He was mine. Providence had given him to me.

I beckoned to the woman and she came closer to the calash.

“You are his mother?” I asked.

No, Madame. His grandmother. His mother my daughter died last winter.

She has left five children on my hands. ” I was exultant.

“On my hands!” It was significant.

I will take little Jacques. I will adopt him. I will bring him up as my child. “

“He is the naughtiest of them all. One of the others …”

“He is mine,” I said, for I loved him already.

“Give him to me and you will never regret it.”

“Madame … you are …”

“I am the Queen,” I said. She dropped a clumsy curtsy and I added:

‘you shall be rewarded. ” And my eyes filled with tears at her gratitude, for like my husband I loved to help the poor when I was made aware of the difficult lives they led.

“And this little one shall be as my own child.”

The little one sat up suddenly and began to cry: “I don’t want the Queen. I want Marianne….”

“His sister, Madame,” said his grandmother.

“He is very wayward. He will run away.”

I kissed him.

“Not from me,” I said, but he tried to wriggle away from me. I signed to Campan to take the name of the woman and to remind me that something should be done; and then I gave orders to return to the palace.

Little Jacques kicked all the way and kept screaming that he wanted Marianne and his brother Louis. He was a bright little fellow.

“You do not know, darling, what a happy day this is for you,” I told him, ‘and for me. “

I told him of the toys he should have . a little pony of his own.

What did he think of that? He listened and said:

“I want Marianne.”

“He is a faithful little fellow,” I said.

“Not to be bribed.”

And I hugged him, which made him wriggle more than ever. His little woollen cap fell off and I was enchanted, for he was much prettier without it. I thought how delightful he would look in the clothes I should plan for him. We should soon discard that red frock and the little sabots.

When we reached the palace there was some astonishment to see me hand in hand with a little peasant boy, who was now too bewildered by all he saw to continue with his tears.

The Queen’s latest folly, was what they called it. But I did not care.

At last I had a child even though he was not of my flesh and blood. I found a nurse for him immediately-the wife of one of my menservants who had children of her own and whom I knew to be a good mother. I gave orders that he was to be suitably dressed as became his new station in life. And then with Madame Campan’s help I set about making arrangements to send my little darling’s brothers and sisters to school.

Those were the happiest days I had known for a long time, and when I saw my little one in a white lace-trimmed frock with a rose-coloured sash trimmed with silver fringe, and a little hat decorated with a feather, I thought he was the most beautiful creature I had ever seen.

I embraced him; I wept over him; and this time he did not object; he lifted those wondering and most beautiful blue eyes to my face and called me “Maman.”

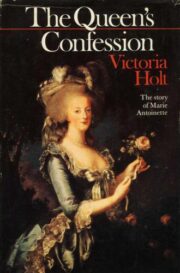

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.