Gabrielle de Polignac sought to comfort me.

How unlucky I am to be treated so,” I said. I laughed. But if it is malicious of people to suppose I have lovers, it is certainly odd of me to have so many attributed to me and to do without them all.”

Gabrielle certainly thought it was odd of me. It was something hardly any woman in our set did without. Of course I was foolish to surround myself with these people. No wonder I was suspected of behaving as they did. Even Gabrielle was Vaudreuil’s mistress. And all these women’s lovers were said to be mine as well because I met them frequently in the apartments of my friends. I should have been content with the companionship of the Princesse de Lamballe and my dear little sister-in-law Elisabeth.

Then Axel, who had always felt very strongly about the cause of American Independence, made up his mind that he would go to America and help to further it.

I was heartbroken, but must keep up a pretence of mere regret at saying goodbye to someone I respected and liked to chat to. Not that I deceived anyone.

“What!” cried one Duchesse when she heard he was going.

“Are you deserting your conquest?”

I pretended not to hear this and I went on smiling blankly at Artois, who was watching me maliciously.

If I had made one,” Axel answered, I should not abandon it. I go without leaving anyone behind to regret my going.”

He would lie for me, because he knew of my feelings. It was the only thing to do. He dared not stay.

So he left. Well, I would devote myself to my child. Rumours of my behaviour had of course reached my mother, though not of Axel specifically. I wrote to her:

“My dear Mother can feel reassured with regard to my con duct. I feel too much the necessity of having children to neglect anything on that score. If in the past I was in the wrong it was due to my youth and irresponsibility, but now you can be sure I realise my duty. Besides, I owe it to the King for his tenderness to me and his confidence, on which I congratulate myself….”

I meant that. I was deeply grateful to my husband for his goodness to me. It was not only fear of having another man’s child which had made me agree that Axel should go away, it was the desire to be a faithful wife and worthy of my husband. I knew that he had never been unfaithful to me; he had never had a mistress. Was he the first King of France to aspire to this virtue? How many women at this Court could say they possessed a faithful husband? His tenderness to me, his desire to please me, that ever-abiding tendresse, surely it demanded some reward? Besides, there was our child.

My little Madame Royale! How I adored her! I saw less of little Armand now. He was bewildered and sad and I would suddenly realise this and send for him and let him lie on my bed with me while I fed him sweetmeats. But the position was changed. He was no longer my little boy. He was merely Armand, to be cared for by servants. What time I had was given to my own little daughter. He was well fed, and had all the material comforts that he had enjoyed before. It did not occur to me that I had acted in my usual thoughtless manner when I had taken him from his home, pampered and petted him and then cast him aside. I forgot this but he never did. He was to remember it in the years to come, he became one of those bitterest enemies who did their share to destroy me.

So even when I had meant to be kind I was helping to build that great force which was to come against me and envelop me and sweep me on to destruction. My mother was writing as often as ever and the theme of her letters was: There must be a Dauphin.

I was keeping tote hours, she had heard from Mercy. Was that the way to get a Dauphin? The King went early to bed and rose early. I went late and rose late. She had heard that at the Trianon where I often was I slept alone. She disapproved of the lit a part. Each month she wanted to hear that I was pregnant and there was no news of this happy situation.

“Up to now I have been discreet, but I shall grow importunate. It would be a crime if there were no more royal children. I am growing impatient, and at my age I have not much time left to me.” I too longed for a Dauphin.

I did try to live more quietly. I read, as my mother would have wished, though perhaps not the books she would have chosen; I liked novels of romance; I did a little needlework and I gambled now and then, although not so heavily as before; but my greatest happiness was with Madame Royale.

The first word she said was “Papa,” which pleased me as much as it did the King. I wrote to my mother:

“The poor little thing is beginning to walk. She has now said ” Papa”;

her teeth are not through yet but I can feel them. I am glad she began by naming her father. “

Each day there was some progress. How thrilled I was when she took her first tottering steps towards me. I wrote and told my mother, of course.

“I must confide to my dear Mother a happiness I had a few days ago. There were several people in my daughter’s room and I asked one of them to ask her where her mother was. The poor little thing, without a word being said to her, smiled and came to me, her arms outstretched. She knew me, the little darling. I was overjoyed and I love her even more than I did before.”

Mercy was grumbling to my mother that I could be talked to of nothing for I would interrupt and tell him that my daughter had her first tooth, had said “Maman,” had walked farther than ever before; that I sr’nt almost the whole day with her; that I listened to his conversation even less than I had before.

It seemed I could never give satisfaction.

Meanwhile my mother continued to write:

“There must be a Dauphin.”

To my great joy I believed I was pregnant again. I was determined to say nothing of this to anyone but the King and a few of my friends. I could not resist whispering it to Gabrielle, and I told the Princesse de Lamballe and my dear Elisabeth and Madame Campan, but I did make them all swear to secrecy until I was absolutely sure.

Then a dreadful thing happened. While I was travelling in my carriage I was suddenly aware of a cold wind, and without thinking I jumped up to shut the window. More effort was needed than I had believed, and I strained myself, with the result that a few days after the event I had a mis carriage.

I was heartbroken. I wept bitterly and the King wept with me.

But we must not despair, he said. We should have our Dauphin in a very short time, be was sure. And in the mean time we had our adorable Madame Royale.

He comforted me and I declared how glad I was that I had not mentioned my condition to anyone except those whom I could trust. I imagined what the Aunts or my sisters-in-law would have made of it. They would have blamed me, my love of pleasure, my indifference to duty . anything to discredit me.

I told my husband how glad I was, and he said that we should keep the secret and I must tell all those who knew of the affair to say nothing of it. I was quite ill for a few days, but my health was so good generally that I quickly recovered.

Then I caught measles, and as the King had not had this complaint I went to the Trianon that I might be alone. I was followed there by those who had had it or decided to risk infection: Artois and his wife, the Comtesse de Provence, the Princesse de Lamballe, and Elisabeth. It was not to be expected that we should stay there without male company, and the Dues de Guines and de Coigny came with the Comte d’Esterhazy and the Baron de Besenval. These four’ men were constantly in my bedroom and did their best to amuse me. This caused a great deal of comment and scandal, naturally. The men were called my sick-nurses; and it was whispered that the measles were non-existent they provided the excuse. They were asking which ladies the King would choose to nurse him if he were ill.

Mercy for once had said that he could see no harm in my having friends at the Trianon to amuse me and help me recover from my illness. The King saw nothing wrong either. Kings and Queens had received visitors in their bedrooms for as long as anyone could remember. It was a tradition to do so.

When I was better I stayed on at the Trianon. I wanted to be there all the time. There were protests from Vienna, and Mercy told me that he had my mother’s permission to remind me that a great Court must be accessible to many people. If it were not, hatreds and jealousies would arise; and there would be trouble.

I listened yawning, thinking of the play I would be putting on in my theatre very soon. I should play the principal part myself. Surely everyone would agree that that was fitting.

The result of this interview was that I wrote to my mother and assured her that I would spend more time at Versailles.

She answered me:

I am very glad that you intend to resume your State at Versailles. I know how tedious and empty it is, but if there is not State the disadvantages which result from not holding it are greater than those of doing so. This applies particularly to your country, where the people are known to be impetuous. “

I did try to do what she suggested, and held State at Versailles, but so many people whom I had offended stayed away. I rarely saw the Due de Chartres, for one. He had retired to the Palais Royale and entertained his friends there. I did not know what they discussed there; nor did it occur to me to wonder.

There seemed no point then in holding Court at Versailles; why should I not spend more and more time at the Pent Trianon, where life was so much more fun, surrounded as I was by the friends I had chosen?

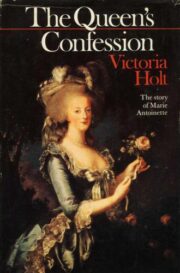

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.