When we were not acting plays we played childish games. The favourite game was called Descampativos, which had derived from blind man’s buff.

One of the players was sent out of the room, and when he or she bad left, the rest of us would cover ourselves completely with sheets. Then the one who was outside would be called in; in turn we would touch him and he would have to guess who we were. The great point about this game was die forfeits which had to be paid, and these became wilder and wilder. Everything we did was exaggerated; the simplest pleasure was described as a Roman bacchanalia. Another game was tire en jam be in which we all mounted sticks and fought each other. This gave rise to a lot of horse-play, and although the King liked to wrestle and play rough games he had little liking for this.

My garden occupied a great deal of my time. I was constantly planning and replanning. I said I wanted it to look as little like Versailles as possible. I wanted a natural garden. Oddly enough it seemed more costly to create that than the symmetrical lawns and fountains which Louis XIV had made so popular. I had plants brought from all over the world; hundreds of gardeners were employed to produce a natural landscape. I wanted a brook running through a meadow, but there was no spring from which the water could be obtained.

“You cannot obtain water!” I cried.

“But that is ridiculous.” And water had to be piped and brought from Marley. Some comments were that it was gold not water that filled the charming little stream at the Trianon. Rustic bridges were built over the stream; there was a pond and an island; and all these had to be created as though nature had put them there.

The price of all this was staggering, only I never considered it. I would yawn as I looked at the amounts; I was never quite sure of the number of noughts; but I was constantly thinking of how I could improve my little world, and it occurred to me that I should create a village, for no rustic scene was complete without people. There should be cottages, I decided, eight of them: little farms with real people and real animals. I summoned Monsieur Mique, one of the most famous of our architects, and told him what I planned. He was enchanted with the idea. Then I asked the artist

Monsieur Hubert Robert to work with Mique. They must build for me eight little farmhouses, with thatched roofs and even dung-heaps. They must be charming but natural.

The two artists threw themselves into the project with enthusiasm, sparing no expense. They were constantly suggesting improvements and I enjoyed my conferences with them. The farmhouses must be made to look like real farmhouses. The plaster would have to be chipped in places; the chimneys must look as if smoke had poured through them.

Natural was the order of the day and no artifice or expense should be spared to achieve it.

When the farmhouses were ready I peopled them with families, selecting them myself. Naturally I had no difficulty in finding peasants who were happy to make their home there. So I had real cows, pigs and sheep. Real butter was made; my peasants washed their linen and spread it out on the hedges to dry.

Everything, I said, must be real.

Thus was created my Hameau. My theatre had cost 141,000 livres; I did not stop to calculate the cost of the Hameau at the time . and later I dared not.

But I was happy there. I even dressed simply there, although Rose Berlin assured me that simplicity was a great deal more difficult to achieve than vulgarity—and naturally more costly.

In a simple muslin gown I wandered along by the brook or sat on a grassy bank so cleverly built that none would have guessed it had not always been there. Sometimes I caught fish and these were cooked; for I had had my stream well stocked with fish as it naturally would be in the country. Sometimes I milked cows, but the floor of the cow house was always cleaned before I came and the cows brushed and cleaned. The milk would fall into a porcelain vase marked with my monogram. It was all very delightful and charming. The cows had little bells attached to them and my ladies and I would lead them by blue and silver ribbons.

It was enchanting. Sometimes I would pick flowers and take them into the house and arrange them myself. Then I would take a walk past the farmhouses to see how my dear peasants were getting on and making sine that they woe behaving naturally.

At least,” I said with satisfaction, ” the people in my Hameau are content. “

And that seemed a very good thing and made worthwhile the great sums of money which continued to go into making the place, for I was constantly adding to its beauties and discovering new ways of improving it.

Letters were arriving from Joseph, but they did not have the same effect as those of my mother. Moreover, that intense devotion which she had felt for me was lacking. Joseph thought me foolish—and he was certainly right in this; he lectured me, but then he lectured everyone.

He was writing to Mercy, of course, and Mercy remained my watchdog as he had during my mother’s lifetime.

Mercy, who was no respecter of persons and never minced his words, showed me what he had written to Joseph. I suppose in the hope that I would profit from it.

“Madame Royale is never apart from her mother and serious business is constantly interrupted by the child’s games, and mis inconvenience so fits in with the Queen’s natural disposition to be inattentive that she scarcely listens to what is said and makes no attempt to understand. I find myself more out of touch with her than ever.” He sighed as I read,-for my attention was straying even as he put the paper into my hands and I was wondering whether a pale pink sash would be more becoming for my darling child rather than the blue one she was wearing.

Poor Mercy! The heart had gone out of him since my mother’s death. Or was he realising at last that the task of rescuing me from my follies was hopeless?

Money I It seemed the constant topic of conversation—and such a boring one! There was apparently a deficit in the country’s finances which it was imperative to rectify: so said Monsieur Necker, who had been appointed as Comptroller-General of Finances. Turgot’s policy had failed and he had been followed by Clugny de Nuis, who had not given satisfaction. This man had not been successful although he had the support of the Parlement (largely because he had tried to undo all the work Turgot had done). He had established a state lottery, which had not worked out as he had planned it should, and his methods were leading to financial disaster. When he died there was a sigh of relief and my husband turned to Jacques Necker.

Necker was a Swiss, a self-made man who owned the London and Paris bank of Thellusson and Necker. He had proved his ability to juggle successfully with finances and was at the same time beloved of the philosophers, having won a prize for a literary work from the Academic Francaise; he had written several attacks on property-owners and deplored the contrast between rich and poor. He was a man of great contrasts perhaps more so than most. He was an idealist, yet he yearned for power. He refused to accept payment for his work; but then he was an extremely rich man and did not need money. He wanted to improve the conditions of the poor; he wanted to bring the country to prosperity; but he wanted all to know that he, Necker, and he alone was responsible for the good which was being done.

He was a Protestant, and since the reign of Henri IV no Protestant had been allowed to hold office. It indicates the impression Necker made on the King for this rule to be waived. Louis, who since he had been King had made a great effort to understand public affairs, was certain that the country needed Necker at this time.

Necker was a big man with thick eyebrows below a high forehead above which was a high tuft of hair. His complexion was yellow and his lips tight, as though he were calculating the cost of everything. He looked incongruous in fine velvets; I said to Rose Benin that he would look better in a Swiss bourgeois costume and that she had better make him one.

“Madame,” she replied, “I choose my clients with the utmost care.

Since I serve the Queen of France, it is my duty to do so. “

Necker, looking round for a means of cutting expenses, examined the royal household. We had too many servants. Madame Royale herself had eighty people in her household. None of us ever moved without being accompanied by a retinue of servants. Four hundred and six people lost their posts on the first day the resolution had been put into action; others followed.

But there seemed no perfect solution, for although we economised in our household, those who were dismissed were without employment.

Necker and his wife felt strongly about the state of our hospitals, and the King, always ready to further such good causes, was entirely in accord with them. The conditions at the Hfitel-Dieu in Paris were truly shocking. My husband went, incognito, and wandered through the wards, and when he came back he was in tears and very melancholy. But France did not want tears; it needed action. He knew this, and planned to pull down the old building and replace it by four new hospitals.

But where was the money to be found? He had to abandon that grand scheme and satisfy himself with enlarging the old building and adding three hundred beds.

And while this was happening my bills at the Hameau were steadily mounting.

Why was my folly not brought home to me? Why did everyone wish to indulge me? And was it indulging me? Was it not giving me -a helping hand towards my doom? Before our daughter had been born my husband had indulged me because he was so apologetic for the embarrassing situation in which he had placed me; afterwards, he could not thank me enough for proving to the world that he could be a father.

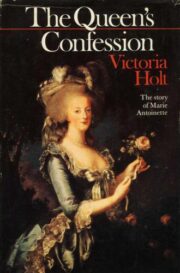

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.