It was a picture of France—the uselessness of the aristocracy and the growing awareness of the shrewd people of the state of their country;

it was meant to set them wondering as to how it could be remedied. I think of little snatches of dialogue.

I was born to be a courtier. “

I understand it is a difficult profession. “

“Receive, take, ask. There’s the secret of it in three words.”

With character and intelligence you may one day rise in your office.

”Intelligence to help advancement? Your lordship is laughing at mine. Be commonplace and cringing and one can get anywhere. “

“Are you a prince to be flattered? Hear die truth, you wretch, since you have not the money to recompense a liar.”

Nobility, wealth, rank, office—that makes you very proud! What have you done for these blessings? You have taken the trouble to be born, and nothing else. “

I was too immersed in my own affairs to be fully aware of the crumbling society in which I was living. I saw nothing explosive in these remarks. To me they were merely excessively amusing. But my husband saw the dangers immediately.

“This man turns everything to ridicule—everything which should be respected in a government.”

“Then won’t it be played?” I asked, showing my disappointment.

“No, it will not,” replied my husband, quite sharply for him.

“You may be sure of that.”

I often think of him now, poor Louis. He saw so much that I could not understand. He was clever; he could have been a good king. He had the best will in the world; he was the kindest, the most amiable of men;

he sought nothing for himself. He had his ministers—Maurepas, Turgot who was replaced by Necker in his turn replaced by Calonne-but none of these ministers was great enough to carry us safely over the yawning abyss which was widening rapidly beneath our very feet. Dear Louis, who wanted to please.

But it was so difficult to please everyone. And what did I do? I was the tool of ambitious factions and did nothing to help my husband, who wanted to please me and wanted to please his ministers, and vacillated between the two. That was his crime: not cruelty, not indifference to the suffering of others, not lechery—not all those crimes which had undermined the Monarchy and set the pillars on which it was erected mouldering to dust: it was vacillation, in which he was helped by a giddy thoughtless wife.

This affair of the play was characteristic of Louis’s weakess and my frivolity.

When Figaro was banned everyone became greatly interested in it. When Beaumarchais declared that only little men were afraid of little writings, how clever that was! And how well he understood human nature I There was no one who wished to be thought a ‘little man,” and his supporters were springing up everywhere. Gabrielle told me that her family believed the play should be performed. What sort of society was this where artists were not allowed to speak their minds I The play could not be performed, but what was to prevent people’s reading it?

“Have you read Figaro’?” It was the constant question asked everywhere. If you had not, if you did not burst into immediate praise, you were a ‘little man or woman. ” Clever Beaumarchais had said so.

There was one section of society which placed itself firmly behind Beaumarchais. Catherine the Great and her son the Grand Duke Paul expressed their approval of the play and declared they would introduce it into Russia. But the most important supporter was Artois. I think he longed for us to play it and therefore he was determined to see it performed. He was as lighthearted as I, and even went so far as to order a rehearsal in the King’s own theatre—Menus Plaisirs. Here my husband showed himself firm for once. As die audience was beginning to arrive he sent the Due de Villequier to forbid the performance.

Shortly afterwards the Comte de Vaudreuil, that most forceful lover of Gabrielle’s, declared that he could see no reason why the play should not be performed privately, and gathered together actors and actresses from the Comedie Francaise, and the play was put on in his chateau at Gennevilliers. Artois was there to see it performed. Everyone present declared it a masterpiece and demanded to know what was going to happen to French literature if its most important artists were muzzled.

Beaumarchais made fun of the censorship in the play itself:

“Provided I don’t speak in my writings of authority, of religion, of politics, of morality, of the officials of influential bodies, of other spectacles, of anyone who has any claim to anything, I can print anything freely, under the inspection of two or three censors.”

This was, many people were declaring, not to be tolerated. France was the centre of culture. Any country which failed to appreciate its artists was committing cultural suicide.

Louis was beginning to waver, and I repeated all the arguments I had heard. If certain offensive passages were removed . “Perhaps,” said the King. They would see.

It was a half-victory. I knew that he could soon be persuaded.

I was right. In April 1784 in the theatre of the Comedie Francaise, Le Manage de Figaro was performed and there was a stampede to get tickets. Members of the nobility stayed all day in the theatre to make sure of their places, and all through the day the crowd collected and when the doors were open they rushed in; they were standing in the aisles; but they listened spellbound to the performance.

Paris went wild with joy over Figaro; he was being quoted all over the country.

A victory for culture! What the nobility did not realise was that it was a step farther in the direction of the guillotine.

I believed that I had been right to add my voice to those who persuaded the King. I wished to show my appreciation of Beaumarchais and to honour him, so I suggested that my little company of friends should perform his play Le Barbier de Seville at the Trianon, in which I myself would play Rosine.

At the beginning of August in that year 1785, five months after the birth of my adorable little Louis-Charles, I was at the Trianon; and I intended to stay there undl the festival of Saint Louis, and. while I was there to play in Le Barbier de Seville.

As always, I was happier there than anywhere else. I remember walking round the gardens to look at the flowers and to see what progress my workmen had made—there were always changes being made at the Trianon—and pausing close to the summer house to look at my theatre with its Ionic columns, supporting a pediment on which a carved cupid held a lyre and a wreath of laurels. I remember the thrill I always experienced when I entered the theatre and the joy I took in its white and gold decorations. Above the curtain concealing the stage were two lovely nymphs holding my coat of arms and the ceiling had been exquisitely painted by Lagrenee. It looked very small with the curtain hiding the stage—that . stage which was my pride and delight—and which was enormous, large enough for the performance of any play; and if the space provided for the audience was small, well, it was a family affair, so we did not need the space of an ordinary theatre.

What I enjoyed most at the Trianon—apart from acting-was what were called the Sunday balls. Anyone could attend if suitably dressed. I had said that mothers with children and nurses with their charges were to be presented to me and I enjoyed talking to these guardians of the little ones about their charming ways and their ailments. I talked to the children and told them about my own. I was happiest then.

Sometimes I would take part in a square dance, passing from partner to partner, to let the people know that the Trianon was conducted without the formality of Versailles.

I was particularly happy at that time, having no idea that a storm was about to break. Why should I have had? It all began so simply.

The King was giving a present of a diamond epaulet and buckles to his nephew, the Due d’Angouleme, son of Artois, and had ordered these through Boehmer and Bassenge, the Court jewellers; he asked them to deliver them to me.

After the manner in which Boehmer had behaved about his diamond necklace before my little daughter I had ordered that he was not to come into my presence but should deal with my valet de chambre.

I was with Madame Campan rehearsing my part in The Barber when the epaulet and buckles were delivered to me. The valet de chambre who brought them told me that Monsieur Boehmer had delivered a letter for me at the same time as he had brought the jewels.

I sighed as I took it. I was really thinking of my part.

“That tiresome man,” I said.

“I do believe he is a little mad.”

One of the women was sealing letters by a lighted wax taper and I went on talking to Madame Campan: “Do you think that I put enough emphasis into that last sentence? Do you think she would have said it in that way? Try it show me how you would do it, dear Campan.”

Campan did it excellently. What a way she had with words! Not that she looked in the least like Rosine . my dear serious Campan I “Excellent!” I said, and opened the letter. I ran my eye over it yawning slightly. Boehmer always made me want to yawn.

“Madame, ” We are filled with happiness and venture to think that the last arrangements proposed to us, which we have carried out with zeal and respect, are a further proof of our sub mission and devotion to Your Majesty’s orders and we have real satisfaction in thinking that the most beautiful diamonds in existence will belong to the greatest and best of Queens. “

I looked up and gave the letter to Madame Campan.

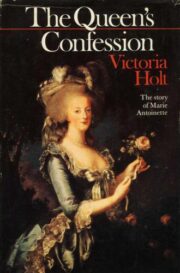

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.