The face of this woman (Baronne d’Oliva) had from the first thrown me into that sort of restlessness which one experiences in the presence of a face one feels certain of having well before without being able to say where. What had puzzled me so much in her face was its perfect resemlance to that of the Queen.

After this fatal moment (the meeting in the Grove of Venus) the Cardinal is no longer merely confiding and credulous, he is blind and makes of his blindness an absolute duty. His submission to the orders received through Madame de la Motte is linked to the feelings of profound respect and gratitude which are to affect his whole life. He wilt await with resignation the moment when her reassuring kindness will fully manifest itself, and meanwhile will be absolutely obedient.

Such is the state of his soul.

Looking back, I see the affair of the necklace as the beginning, as the first rumble of thunder in the mighty storm which was to break about my head. I was determined that Rohan should be judged and found guilty; he must be exposed as the swindler I believed um to be. Should he be excused because he was a prince of a noble family? I owed it to my mother as well as my own dignity as Queen of Prance to have him proved guilty of all the sins which I was certain he had committed.

I laughed when I considered what I was sure his family expected. They would imagine that the King would exercise his right to inflict a mild punishment on the Cardinal, perhaps send him a lettre de cachet which would mean a brief exile; then he could return to Court and the incident be for gotten.

I was determined that this should not be.

Louis, as usual, wavered. His good sense told him that he should listen to wise counsellors and obey his own instincts in the matter, which were that the less universally known about the matter the better for us all; but his sentiments towards me and he loved me truly insisted that he listen to my outbursts of fury against a man who had dared presume that I would enter into an underhand negotiation with him. Whenever Rohan’s name was mentioned, I would burst into an angry tirade which often ended in tears.

“The Cardinal must be punished.”

Louis pointed out that the Cardinal belonged to one of the oldest families in France; he was related to the Condes, the Soubises and the Marsans; they believed that they had been personally insulted since a member of their family had been arrested publicly like a common felon.

“Which be isl’ I declared.

“And the whole world should know it.”

“Yes, yes,” replied my husband, ‘you are right, of course. Yet not only his family but Rome itself is displeased that a Cardinal of Holy Church should have been submitted to insult. “

“And why not,” I demanded, ‘when he deserves his fate more than some man who steals bread because he is hungry. “

“You are right,” said my husband.

I embraced him warmly.

“You will never allow a man who has insulted me to go free, I know.”

“He shall have his just rewards.”

All the same Louis allowed the Cardinal to decide whether he would be judged by the King or the Pariement.

He quickly made his choice and wrote to the King, and it struck me at the time that the man who had written that letter to my husband had changed a great deal from the frightened creature who had been summoned to the King’s cabinet on the day he was arrested. He had written:

“Sire, I had hoped through confrontation to obtain proofs that would have convinced Your Majesty beyond doubt of the fraud of which I have been the plaything and I should then have desired no judges except your justice and your kindness. Refused confrontation and deprived of this hope, I accept with most respectful gratitude the permission which Your Majesty gives me to prove my innocence through judicial forms; and consequently I beg Your Majesty to give the necessary orders for my affair to be sent and assigned to the Pariement of Paris, to the assembled chambers.

“Nevertheless if I could hope that the inquiries which have been made, and which are unknown to me, could have led Your Majesty to decide that I am only guilty of having been deceived, I should then beg you.

Sire, to decide according to your justice and your kindness. My relations, penetrated with the same sentiments as myself, have signed.

“I am, with the deepest respect, Cardinal de Rohan De Rohan, Prince de Montbazon Prince de Rohan, Archbishop of Cambrai L.M. Prince de Soubise’ When my husband read this letter he was disturbed. He too was struck by the change in Rohan. His imprisonment in the Bastille had changed him from a very frightened man to an arrogant one.

I could see the speculation in his eyes. He said to me: “If I admitted that the Cardinal is merely a man who has been deceived into taking part in this fraud, he would not wish to be tried by the Parlement.”

I laughed aloud.

“I dare say not. He would rather have your leniency than a judicial sentence when he is proved guilty.”

“What if he is not proved guilty?”

‘you are joking. Of course he will be proved guilty. He is guilty.”

My husband looked at the letter; he was staring at those names at the foot of it—some of the most influential in the country.

I knew that he was hoping that the matter might be hushed up in some way, which I told myself was just what Rohan’s noble family wanted.

But I was determined to bring this affair into the open.

My folly makes me shudder even now.

The most important affair in France was the trial. Information was leaking out daily. The Comtesse de la Motte Valois had been arrested; so had Cagliostro, the notorious magician, and his wife; and so had another creature, a girl of light morals who was known as the Baroness d’Oliva and who was said to have impersonated me. The story was growing more and more fantastic every day. There had been nothing compared with this since the ascent of the balloon which had amazed everyone. But this was even more exciting; this was a trial of a great Cardinal; it was the story of a great fraud, a fabulous diamond necklace which had disappeared from the scene; it was a story of scandal and intrigue, and at the very heart of it was the Queen of France.

I was unaware then of all the twists and turns of this incredible story; but I have since heard many versions of it. In fact I have never ceased to hear of it. It was not really so much the Cardinal de Rohan who stood on trial; it was the Queen of France.

How could I have prevented what was to happen? By being a different woman. By never having entered on a life of selfish pleasure. I was not guilty of all of which I was accused in this nightmare story of a diamond necklace. My tragedy was that my reputation was such that I could have been.

I must set down the story of the Diamond Necklace, which gradually came to my knowledge while the tension was growing over that trial—and during it.

As I learned it I lost my carelessness. I believe this was the first time I really began to understand the mood of Prance, that I first became aware of that crumbling pedestal which supported the Monarchy.

The Prince de Rohan was at the very centre of the drama; he was the dupe, it seemed; but bow a man of his education and culture could have been so easily duped it is difficult to understand; perhaps it had something to do with the strange Cagliostro who was arrested with Rohan and who remains a vague and shadowy figure, the mystery man. Magician or charlatan? That is something I shall never know.

Perhaps the most important figure in the whole unsavoury affair was the Comtesse de la Motte-Valois, that woman who, from afar, since this unfortunate affair occurred, has been writing her sensational lying and pornographic stories of my life—my enemy whom I have never met, to whom I have done no harm except to have ascended the throne of France. Hers was an unusual story. She claims descent from the royal Valois, that branch of the family of France which ruled before the Bourbons. She was the daughter of a certain Jacques Saint-Remy, who claimed descent from King Henri II. This appeared to be the truth, for Henri II had had an illegitimate son by a certain Nicole de Savigny, and this child, christened Henri after him, was legitimised by him and created Baron de Luz and de Valois.

Jeanne suffered great poverty in her childhood, but she had heard that she was descended from the Valois and never forgot it. In the days when she was living on the proceeds of her great fraud she bore the arms of her family—Sargent a une fasce d’azur, char gee de trois fleurs de Us for—on her carriage, in her house, anywhere where she could put it.

The child Jeanne was brought up in a state of abject poverty, and this, added to the knowledge that she was of royal blood, may well have been

at the root of her hatred for me and her desire to gain, at any cost, the status which she believed belonged to her.

No doubt when Henri de Saint-Remy, son of Henri II, lived in the chateau it had been a beautiful place, but during the years which followed, the Saint-Remys found it impossible to keep up their standard of living; the ditches about the chateau became filled with stagnant water; the roof had fallen in and the upper part was exposed to the weather. By the time Jeanne’s father was born, it was a ruin.

He was a man of great physical strength but had not desire to regain his family’s fortunes if it meant work. He was only interested in drink and debauchery, and gradually sold little by little, all that remained of the chateau.

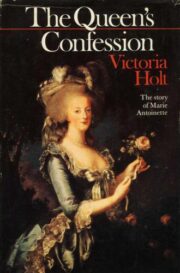

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.