And then Cagliostro, in green silk embroidered with gold.

“Who are you and whence do you come?” he was asked.

“I am an illustrious traveller,” he cried in loud tones which provoked laughter; but he soon silenced that with his colourful invective, and I believe that there were many who though they laughed in the courtroom by day were in truth afraid of what such a notorious sorcerer might do to them.

And so they stood before the judges—the handsome Cardinal, the wild, beautiful and scheming Comtesse, the charming young courtesan with her baby at her breast, the adventurer Villette, and the fantastic magician, sorcerer or wise man. Everyone was awaiting the verdict of the judges which was of the utmost importance to all these people on trial—and perhaps equally so to me.

The judgment was given on Wednesday 31st May and the court opened at six o’clock in the morning. From five o’clock the streets had been filling and crowds had gathered in front of the Palais de Justice.

Guards, mounted and on foot, kept the crowds in order from the Font Neuf to the Rue de la Barillerie.

In the entrance of the Grande Chambre members of Rohan’s family had assembled; they were all dressed in mourning and had doubtless placed themselves there as a warning to the judges who must pass by them. They wished to imply that to do anything but acquit the Cardinal would be an outrage against the nobility.

It became quite clear that the Rohans were determined to bring their relative out of that court acquitted of all guilt. For this reason, as Madame de la Motte was judged first and judged guilty for how could it be otherwise in view of the evidence two of the judges declared their intention to press for the death penalty. This was a ruse on the part of these men because if a case was being judged which might incur the death penalty no cleric must sit in judgment. Of the thirteen clerics among the judges only two were favour able to Rohan, therefore by removing them from the seat of judgment, although the Rohans lost two votes in their favour, they rid themselves of eleven against. Such was the power of the Rohans.

Madame de la Motte was not sentenced to death but she was condemned to be whipped naked by the executioner, marked with the letter V for volense on her shoulder, and imprisoned in the Salpetriere for the rest of her life. Her husband though not present to pay the penalty of his crimes was sentenced to the galleys for life; Retaux de Villette was exiled and Oliva was acquitted, but not without blame, for she had actually taken part in the scheme to impersonate me.

Cagliostro was dismissed from every charge.

There remained the chief figure in the drama the one whose presence in it was responsible for the great interest throughout the country.

An absolute acquittal was demanded. The Cardinal had been the dupe of scoundrels but his good faith was un deniable. He was absolutely innocent.

“It is innocence, gentlemen,” declared his counsel, ‘that I am defending, as a man and as a judge; and I am so thoroughly penetrated with my belief that I would allow myself to be hacked to pieces in maintaining it. “

The battle was over. After sixteen hours of deliberation the Car d inal was acquitted without a stain on his character.

In the streets they were shouting. The women of the fish-market had assembled outside the Bastille with roses and jasmine. The Parisian crowds—the most easily excited in the world—were roaring their approval.

“Long live the Parlement. Long live the Cardinal.*

When I heard the verdict I suddenly realised its implicaon.

This was the biggest defeat I had ever suffered. In giving their verdict the Parlement had implied that it was not unnatural for the Cardinal de Rohan to expect that I would make arrangements to meet him in the park at Versailles; it was not unnatural to think that I could be bought by a diamond necklace!

I was overcome with honor. I threw myself on to my bed and wept. When Madame Campan found me there she was alarmed by my wild grief and sent for Gabrielle to come and comfort me.

When I saw them there in my bedchamber, those two dear women whom I trusted and knew to be my friends, I cried:

“Come and lament for your Queen, insulted and sacrificed by cabals and injustice.” Then I was angry suddenly. The French hated me. In that moment I hated them.

“But rather let me pity you as Frenchwomen,” I went on.

“If I have not met with equitable judges in a matter which affected my reputation, what could you’ hope for in a suit in which your fortune and your character were at stake?”

The King came in and shook his head sadly.

He said: “You find the Queen much afflicted. She has great reason to be so. They were determined throughout the affair to see only an ecclesiastical Prince—a Prince de Rohan; while he is in fact a needy fellow. And all this was but a scheme to put money in his pockets, in endeavouring to do which he found himself the party cheated instead of the cheat. Nothing is easier to see through; and it is not necessary to be an Alexander to cut this Gordian knot’

I looked at him, this kind but most ineffectual man; and I thought then of that day when they had brought us news that we were King and Queen of France and how we had cried: “We are too young to govern.”

How right we were! We were more than too young; we were unequal to this great task—he through his inability to make a decision even when he knew the right one, and I . I was the foolish featherhead my brother Joseph had said I was—the silly child my mother had known me to be and feared so much because of it.

But at least now I knew this; and it was something I had not fully realised before.

The sentence was carried out on Madame de la Motte on the steps of the Palais de Justice. As was expected, she did not submit lightly. She struggled and bit her jailers, and when the V was about to be branded on her shoulder she writhed so violently that she received it on her bare breast instead. Afterwards she was carried off fainting to the Salpetriere clad in sackcloth with only sabots for her feet, to live on black bread and lentils for the rest of her life. No sooner had her punishment been carried out than the people of Paris declared her to be a heroine. The Due and Duchesse d’Orleans collected on her behalf; good things were senr to the Salpetriere. My foolish Lamballe was caught up in the general enthusiasm and took some delicacies to the prison which immediately gave rise to the rumour that I had sent her because my conscience troubled me. Then came the rumour that the story told by Madame de la Motte was true; that she had indeed acted on my behalf. It seemed, although I did not know it then, that the diamond necklace would never be forgotten.

A few weeks after her incarceration in her prison Madame de la Motte was allowed to escape and it was whispered that I had arranged it.

But when the libels began to pour in from England, for Madame de la Motte took to her pen when she reached that country, people still repeated this ridiculous story. The self-styled Comtesse was received in various English houses where she told lurid stories of life at the French Court, and I was always a prominent feature in them.

Having wronged me once it seemed she was impelled to go on doing so.

This was a turning-point in our lives and we knew it, both Louis and I. He was so good to me. He believed in my virtue, and I was grateful to him. He was tender and kind; but he did not understand how the earth was opening before us.

Now I know that had he stood firm then he might have saved us. Had he shown himself resolute in the face of the Parlement he might have kept some of that long-standing respect for the Monarchy which was fast crumbling away.

He should have been strong with me in the first place. He should never have allowed the affair of the necklace to be publicly known. It should have been investigated in private and settled in private.

“No one is more pleased than I am that the innocence of the Cardinal has been established,” he declared.

But because I was so unhappy, so upset sensing the great disaster of this affair, he sent a lettre de cachet to the Cardinal exiling him to his Abbey of Chaise-Dieu.

He exiled Cagliostro and his wife. This was his weakness.

If he disagreed with the Parlement he should have shown that disagreement: instead of which he accepted it, and then agreed to the exile.

I could not rid myself of the terrible depression which had come to me.

Mercy wrote to my brother:

“The Queen’s distress is greater than seems reasonably justified by the cause.”

It was true. But some intuition warned me that what had happened to me was the greatest disaster I had ever faced. I did not understand fully. I merely knew that it was so.

I had lost my light-heanedness. I felt I would never be gay and carefree again.

Madame Deficit

When waste and unthrift deplete the royal treasury there arises a cry of despair and terror. Thereupon the finance minister has recourse to disastrous measures, such as, in the last resort, that of debasing the gold currency or the imposition of new taxes. It is certain that the present government is worse than that of the late King in respect of disorderliness and extortion. Such a condition cannot possibly continue much longer without catastrophe resulting.

I am worried about the health of my eldest boy. His growth is somewhat awry, for he has one leg shorter than the other and his spine is a little twisted and unduly prominent. For some time now he has been inclined to attacks of fever and he is thin and frail.

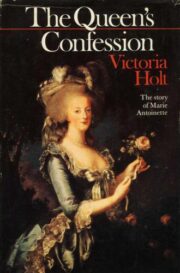

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.