He laughed and I laughed with him, but as always I was near to tears.

The air of Versailles was perhaps not pure enough for him. La Muette would perhaps be better, suggested one of the doctors.

It is unprotected from the cold winds,” said another.

Ah, but those winds sweep the air clear. “

“Monseigneur’s chamber at Versailles is damp,” said Sabatier.

“The windows look on the Swiss Lake, which is stagnant.”

“Nonsense,” replied Lassone.

“The air of Versailles is healthy.”

My husband remembered that when he was a child he had been sent to Meudon and the air there was said to have made him stronger.

Louis had made the decision. The Dauphin was sent to Meudon.

The members of the States-General were to assemble in Versailles. I was afraid of the States-General, because I was aware of an anxiety among those whom I considered to be my true friends. Axel on those occasions when we exchanged a word or two made me aware of his alarm.

I knew that he considered the position very grave and that he was afraid for me.

“Louis,” I said to my husband, ‘would it not be better to hold the Assembly some distance from Paris? “

“They must come to Versailles and the capital,” my husband replied.

“They will rob you of your power and your dignity,” I said. I was certain of it. They were elected from all classes of society. Members of the lower classes would have a say in the affairs of the Government. It was a state of affairs that neither Louis XIV nor Louis XV would have tolerated. But my husband assured me that it was necessary.

There were great preparations for the opening ceremony; hopes had risen in the country; it seemed as though everyone was hoping for a miracle from the States-General.

When I went to Meudon to see my son I forgot all my anxieties about the coming ordeal—for I must take my place in the procession—because the Dauphin was clearly rapidly failing.

His face lit up when he saw me.

“The best times,” he said, ‘are when you are with me. “

I sat by his billiard table holding his hand. What should I wear, he wanted to know.

I told him that my gown was to be of violet, white and silver.

That will be beautiful,”” he said.

“If I were strong and well I should ride in the carriage with you.”

“Yes, my darling. So you must get well quickly.”

“I could not do it in time, Maman,” he said gravely. And then: “Maman, I want to see the procession. Please, please let me see you ride by. I want to see you and dear Papa.”

“It would tire you.”

“It never tires me to see you. It makes me feel better. Please, Maman.”

I knew that I could not deny him this and I told him that it should be arranged.

The bells were ringing and the sun shone brightly. This was the 4th of May in the year 1789—the year of the assembling of the States-General. The streets of Versailles were colourful with decorations and everywhere the fleur-delis was fluttering in the light breeze. I had heard that there was not a single room to be found in Versailles.

There was optimism everywhere. I heard it whispered that the old methods were passing, now that the people were to have a hand in managing the country’s affairs. That was what the States-General was all about. The King was a good man. He had invited the States-General.

Taxes were to be abolished—or equally shared. Bread would be cheap.

France was to be a heaven on earth.

I remember that day clearly. I was so unhappy. I hated the warm sunshine, the faces of the people, their cheering voices (none of the cheers were for me). The bands were playing. There were the French and Swiss Guards. Six hundred men in black with white cravats and slouched hats marched in the procession. They were the Tiers Etai, deputies of the commoners from all over the country; there were three hundred and seventy-four lawyers among them. Following these men were the Princes, and the most notable of these was the Due d’Orieans, who was already well known to the people as their friend. What a contrast the nobles made with those men in black—in lace and gold and enormous plumes waving in their hats. There were the Cardinals and Bishops in their rochets and violet robes— a magnificent sight. No wonder the people had waited for hours to see them pass. In that procession were men whose names were to haunt me in the years ahead—Mirabeau, Robespierre; and the Cardinal de Rohan was there too.

My carriage was next. I sat very still looking neither to right nor left. I was aware of the hostile silence. I caught whispers of “The Austrian Woman!”

“Madame Deficit.”

“She is not wearing the necklace today.” Then someone shouted “Vive d’Orieans.” I knew what that meant.

Long live my enemy. They were shouting for him as I rode by.

I tried not to think of them. I must smile. I must remember that my little son would be watching the procession from the veranda over the stables where I had ordered he should be taken.

I thought of him instead of these people who showed so clearly that they hated me. I said to myself: “What should I care for them? Only let him grow strong and well and I shall care for nothing else.”

I could hear the crowd shouting for my husband as his carriage came along. They did not hate him. I was the foreigner, the author of all their misfortunes. They had chosen me for the scapegoat.

How glad I was to return to my apartments, the ordeal over.

I was sitting at my dressing-table, my women about me. I was tired, but I knew I should not sleep when I retired to bed. Madame Campan had placed four wax tapers on my toilette table and I watched her light them. We talked of the Dauphin and his latest sayings and how he had enjoyed the procession; and suddenly the first of the candles went out of its own accord.

I said: “That is strange. There is no draught And I signed to Madame to relight it.

This she did, and no sooner had she done so than the second candle went out.

There was a shocked silence among the women. I gave a nervous laugh and said: “What candles are these, Madame Campan? Both go out.”

“It is a fault in the wick, Madame,” she said.

“I doubt not.” Yet the manner in which she said it suggested that she did doubt her statement.

A few minutes after she had lighted the second candle the third went out.

Now I felt my hands trembling.

“There is no draught,” I said.

“Yet three of these candles have gone out … one after another.”

“Madame,” said my good Campan, it is surely a fault. “

There have been so many misfortunes,” I said.

“Do you think, Madame Campan, that misfortune makes us superstitious?”

“I believe this could well be so, Madame,” she answered.

“If the fourth taper goes out, nothing can prevent my looking upon it as a fatal omen.”

She was about to say something reassuring when the fourth taper went out.

I felt my heart heavy. I said: “I will go to bed now. I am very tired.”

And I lay in bed, thinking of the hostile faces in the procession, the whispering voices; and of the little face which I had seen from the stable veranda.

And I could not sleep.

We were summoned to Meudon—Louis and I—and we set out with all speed.

I sat by my son’s bed; he did not wish me to go. His hot little hand was in mine and he kept whispering, “Maman, my beautiful Maman.”

I felt the tears running-down my cheeks and I could not stop them.

“You are crying for me, Maman,” he said, ‘because I am dying, but you must not be sad. We all have to die. “

I begged him not to speak. He must save his breath.

“Papa will look after you,” he said.

“He is a good kind man.”

Louis was deeply affected; I felt his hand on my shoulder, kind and tender. It was true he was a good man. I thought of how we had longed for children, how we had suffered because we could not have a son, and now how we suffered because we had one.

Little Louis-Joseph was fighting for his life. I think he was trying to cling to it because he knew I so much warned him to live. He was thinking of me even in those last moments.

I cried to myself: “Oh God, leave me my son. Take anything from me but leave me my son.”

But one does not make bargains with God.

I felt a warm hand in mine and there was my youngest boy. Louis had sent for my daughter and son to remind me that they were left to me.

On one side of me my lovely ten-year-old daughter, and on the other, four-year-old Louis Charles

“You should comfort your mother,” said the King gently.

And I held my children close to me and was, in some measure, comforted.

The Fourteenth of July

2th June 1789: Nothing. The stag was hunted at Saint-Appoline and I was not there. ith July 1789; Nothing.

MADAME CAMPAN MEMOIRS

I have just come from Versailles. Monsieur Necker is dismissed. This is the signal for a St. Bartholomew’s day of the patriots. This evening the Swiss and German battalions will slit our throats. We have but one resource: To Arms.

CAMELLE DES MOULINS AT THE PALAIS ROYALE

Still the people spoke of the King with affection and appeared to think his character favourable to the desire of the nation for the reform of what was called abuses; but they imagined that he was restrained by the opinions and influence of the Comte d’Artois and the Queen; and those two august personages were therefore objects of hatred to the malcontents.

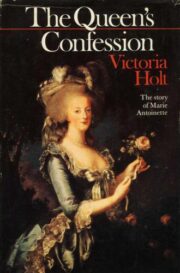

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.