I thought strangely enough of the little clock which my son so loved and which played a tune.

I beard the tinkling sound quite clearly.

“II pleut, il pleut berg ere Presse tes blancs moutons …”

Listen,” I said.

“What is that?”

It was the sound of blows on the door of the Oeil de Boeuf.

We waited. I think even Louis believed then that our last hour had come.

Then . the blows ceased. One of the pages came running in to tell us that the Guards were driving the mob out of the chateau.

I sat down and covered my face with my hands.

My son was pulling at my skirt.

“Maman, what are they all doing?”

I just held him against me. I could not speak. My daughter took her brother’s hand and said: “You must not worry Maman now.”

“Why?” he wanted to know.

“Because there are so many things to think of I thought: They will kill my son. He smiled at me and whispered: ” It’s all right, Maman, Moufflet is here. “

“Then,” I whispered back, ‘it is all right. “

He nodded.

In the Cour Royale and the Cour de Marbre they were shouting for Orleans. I shivered. How deeply was the Due d’Orieans involved in this?

Elisabeth had taken the Dauphin on to her knee; I felt comforted to have Elisabeth with us.

“Maman,” said my son, “Chou d’Amour is hungry I kissed him.

“In a little while you shall eat.”

He nodded.

“Moufflet too,” he reminded me, and we all smiled.

The crowds outside the chateau were shouting for the King.

“The King on the balcony I looked at Louis. He stepped out. They must admire him, surely. He showed not a vestige of fear. They were not to know that he felt none.

La Fayette had arrived to the apartment. He was clearly amazed that the mob had broken into the Palace. He had had their word.

I was not surprised that he was nicknamed General Morphee; he would have been fast asleep in his bed while the assassins were breaking into the chateau.

Provence arrived with the Due d’Orieans, both well-shaven and powdered. Provence looked cold as usual and Orleans sly. Madame Campan told me afterwards that there were many who swore they had seen him disguised among the rioters in the early morning and that he was the one who had shown the mob the way to my apartments.

La Fayette made his way to the balcony.

“The King,” roared the crowd.

La Fayette, bowing, presented the King. The General lifted his hand and told them that the King had now consented to the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Much had been achieved and now he knew they would wish to go home. He, the Commander of the National Guard,”re quested them to.

Did he expect them to obey him? He could not have been such a fool. He was a man playing a part the part of hero of the hour.

Of course the crowd did not move. They were going to have what they had come for.

Then a voice shouted: “The Queen. The Queen on the balcony.”

The cry was taken up. Now it was a deafening roar.

No,” said the King. You must not …”

Axel was there. He made a step towards me but I ordered him with my eyes to keep away. He must not betray our love before all these people. That could only add to our troubles.

I stepped towards the balcony.

My daughter began to cry and I said: “It’s all right, darling. Don’t be frightened, little Mousseline. The people only want to see me.”

It was Axel who thrust my daughter’s hand in mine and, lifting my son, put him in my arms.

No! “I cried.

But he was pushing me on to the balcony. He believed the people would not harm the children.

There was silence as I stood there. Then they cried:

“No children. Send the children back.”

I was sure then that they were going to kill me. I turned and handed the Dauphin to Madame de Tourzel. My daughter tried to cling to my robe but I pushed her back.

Then alone I stepped on to the balcony. There was buzzing in my head but perhaps it was the whispering below me. It seemed to take me minutes to make that one short step. It was as though time itself had stopped and the whole world was waiting for me to cross the threshold between life and death.

I was alone and defenceless facing those people who had come to Versailles to kill me. I had folded my hands across my gold-and-white striped robe into which I had been hastily put when I was aroused from my bed, my hair fell about my shoulders.

I beard a voice cry: Now, there she is. The Austrian Woman. Shoot her. “

I bowed my head as though to greet them; and the silence went on and on.

What happened in those seconds I do not know except that the French are the most emotional people in the world. They love and hate with more vehemence than others. All their feelings are intense, and the more so, perhaps, for being transient.

My apparent lack of fear, my extreme femininity perhaps, my cool indifference to death, touched them momentarily.

Someone shouted: “Vive la Heine’ And others took it up. I looked down on that sea of faces on those disreputable people with their knives and cudgels and their cruel faces. And I was not afraid.

I bowed once more and stepped into the room.

There I was received by a few seconds of bewildered silence. Then the King was embracing me with tears in his eyes and my children clinging to my skirts were crying with him.

But this was a momentary respite.

The crowd was shouting again: “To Paris. The King to Paris.”

The King said this matter must be discussed with the National Assembly. They should be invited to come to the Palace.

But the people outside were growing restive.

“To Paris,” they chanted.

“The King to Paris.”

Saint-Priest was gloomy. So was Axel.

“They will break into the chateau,” he said.

“It is clear. Monsieur de La Payette, that you have no power to restrain them,” La Fayette could not deny this.

“I must save further bloodshed,” said the King.

“I will go peaceably to Paris.” He turned to me and said quickly: “We must be together … all of us.”

Then he stepped on to the balcony and said: “My friends, I shall go to Paris with my wife and children. I shall mist what is most precious to me to the love of my good and faithful subjects.”

There were shouts of joy. The journey had been a success, the mission carried out.

La Fayette stepped from the balcony into the room.

“Madame,” he said gravely, ‘you must consider this. “

“I have considered,” I answered.

“I know that those people hate me. I know they are intent on murdering me. But if that is my fate I must accept it. My place is with my husband.”

It was one o’clock when we left Versailles. Yesterday’s rain had given place to sunshine and it was a lovely autumn day, but the weather could not lift our spirits.

In the carriage in which I rode with the King were my children and Madame de Tourzel, with the Comte and Comtesse de Provence and Elisabeth.

I shall never forget that drive, and although I was to experience greater humiliations, greater tragedies, it stands out in my mind. The smell of the people; their leering faces beside our carriage; the murderous looks which came my way; the long slow drive which took six hours. I could smell blood in the air. Some of these savages had murdered guards and carried their heads before us on pikes—a grim warning, I suppose, of what they would do with us. They had even forced a hairdresser to dress the hair on these heads; the poor man, revolted and nauseated, had been obliged to do so at the point of a knife.

Astride the cannon were drunken women who shrieked obscenities to each other. My name was mentioned often;

I was too sickened to care very much what they said of me. Some of the women, half-naked, for they had not bothered to replace their skirts, went arm in arm with the soldiers. They had robbed the royal granaries, and carriages had been loaded with sacks of flour which were well guarded by the soldiers. The poissardes danced about the carriage crying:

“We shall no longer lack bread. We are bringing the baker, the baker’s wife and the baker’s boy to Paris.”

My little son was whimpering: “I’m so hungry, Maman. Chou d’Amour has had no breakfast, no dinner….”

I comforted him as best I could.

And at last we came to Paris. Bailly the Mayor welcomed us by the light of torches.

“What a splendid day,” said the Mayor, ‘when Parisians are at last able to have His Majesty and his family in their city. “

“I hope,” replied Louis with dignity, ‘that my stay in Paris will bring peace, harmony and obedience to the laws. “

Tired out as we were we must drive to the Hotel de Ville.

There we sat on the throne where the Kings and Queens of France had sat before us. The King told Bailly that he should tell the people that it was always with pleasure and confidence that he found himself among the inhabitants of his good city of Paris.

Bailly when repeating this left out the word ‘confidence’ and I noticed this at once and reminded Bailly of his omission.

‘you hear, gentlemen,” said Bailly.

“This is even better than if my memory had not betrayed me.”

They were mocking us. They were pretending to treat us as King and Queen when we were merely their prisoners.

And then we were offered a brief respite. We were allowed to drive from the Hotel de Ville to the Tuileries—that gloomy, deserted palace which they had chosen for us.

Tuileries and Saint-Cloud

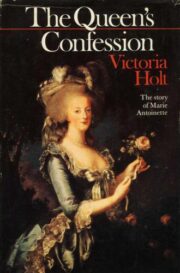

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.