When I remember the letters I wrote to Mercy I know how great the change was.

“The more unfortunate I am,” I wrote, ‘the stronger grows my affection for my true friends. I am looking forward so much to the moment when I shall be able to see you freely and to assure you of the feelings which you have every right to expect from me feelings which will last to the end of my life. “

At last I realised the worth of Mercy, for now I saw how different everything might have been if I had paid attention to his warnings and those of my mother.

But I took courage from the fact that now I could see that I was wrong a fact of which I had been ignorant until great suffering opened my eyes.

During that dreary winter the days seemed long and monotonous. My great comforts were my children and Axel, who was able to visit me frequently. I would sit in the schoolroom white the Abbe Davout was teaching nay son, and I saw how difficult he found it to concentrate, which reminded me so much of my own childhood that I warned him against this.

“But, Maman,” he said gravely, ‘there are so many soldiers here, and they are so much more interesting than lessons. “

Great soldiers, I reminded him, had to learn their lessons too.

We all attended Mass each day and took our meals together We were more intimate than we had ever been before, for we lived like a bourgeois family, sitting at table with the children, who joined in the conversation. Poor Adelaide and Victoire had changed very much.

Sophie had died and they were always saying: “Lucky Sophie. To have been spared this.”

But they were no longer my enemies; this misfortune had changed them too. They had enough sense to realise that the scandals they had spread about me in the past had played a strong part in bringing us all to the state in which we now found ourselves, and they were contrite. I think they were astonished too that I bore them no malice.

I had no time to be vindictive; I could take no pleasure in reminding them of all the harm they had done me. I could only be sorry for them who had lived so long in a state of society which was now cracking under their feet and leaving them defenceless.

Their attitude towards me had taken a complete turnabout;

they were affectionate and devoted perhaps even adoring, for Adelaide could never do anything by halves, and Vktoire, of course, followed her sister.

Elisabeth’s natural saintliness was increased. She was always with me and the children. Together we set about making a tapestry rug, which filled long hours of that winter as pleasantly as could be expected.

After dinner the King would slump in his chair and sleep, or go to his apartment to do so. He was gentle with the whole family and could always soothe the hysterical outbursts of the aunts which they could not help letting escape from time to time. They longed so much for a return of the old days;

they, more than any of us, found it hard to adjust them selves to the new regime.

I lived for Axel’s visits. We could not be alone together but we held many whispered conversations. He told me he could not rest while I was here in Paris. He thought continually of that terrible drive from Versailles to Paris.

“Those canaille how I loathe them! How I despise them! God knows what harm they might have done you. How can I tell you of the agonies I suffered when I knew you were in their midst? I tell you I will never rest until you are out of this city. I want you right away … where I know you shall be safe.”

I smiled and listened. His love for me, my children’s affection for me and my husband’s tenderness were all I cared to live for.

And during that long winter the theme of my lover’s discourse was Escape.

After a while my fears were lulled a little. We; were in a sense prisoners, but at least at the Tuileries we had a semblance of a Court. La Fayette was a constant visitor and he assured the King that he was his servant. La Fayette was a man of good intentions, and in this respect he was not unlike Louis. He failed to be on the spot at the important moment; he was always too late when the decision should be made promptly and too quick when it needed a great deal of consideration. But we were glad of his friendship.

He had evidence that Orleans had helped to arrange the march on Versailles and was certain that those people who swore they bad seen the Due disguised in a slouch hat had not been mistaken, and for this reason he believed that Orleans should be sent where he could do no more harm.

The King could not believe that his own cousin could be such a traitor. But La Fayette cried: “Sire, his plan is to dethrone you and be Regent of France. The very fact of his birth makes this possible.”

“What proof have you?” asked the King dismayed.

“Plenty, Sire. And I can get more. The rabble which marched on Versailles was strongly augmented by men in women’s clothes. They were not the women of Paris as we were meant to believe. They were paid agitators, many of them, and one of those who organised the march was Monsieur d’Orleans.”

“It is incredible,” insisted the King; but I pointed out to him that it was not incredible at all. Orleans had been my enemy from the days when I had first come to France; and I could well believe this of him.

The King looked at me helplessly, but La Fayette, sure now of my support, went on: “Sire, some heard the cry ” Vive Orleans, notre roi d’orleans I think that makes it clear. He plans to destroy you and the Queen and set himself up in your place. He should be sent out of the country. “

“Let him go to England,” said the King.

“But I think it should be said that he goes on a mission for me. I would not wish publicly to accuse my cousin of treachery.”

So to London went Orleans; and there he met Madame de la Motte and together they planned what further calumnies they could pile upon me.

Those long winter days! Those draughty corridors ! Those smoking lamps! And our privacy continually disturbed by the guards!

I do not think I could have endured that winter but for Axel’s presence. I missed Gabrielle sadly. The Princesse de Lamballe was a good friend and I loved her dearly, but she had never had the place in my feelings which I-gave to Gabrielle. Elisabeth was a constant consolation—and of course the children. My daughter was growing into a sweet-natured girl. She was resigned and accepted hardship without complaint. She was greatly influenced by the attitude of her Aunt Elisabeth, and the two were always together. Sometimes when I was particularly sad I would send for my little Chou d’Amour and he would enliven me with his precocious sayings. Like the child he was, he had quickly adapted himself to the life at the Tuileries, and I sometimes thought that he had forgotten the splendours of the Trianon and Versailles.

We must be careful not to spoil him,” I told Madame de Tourzel, ” but he is such a darling, it is difficult. We must remember, though, that we should bring him up to be a King. “

She agreed with me, and I often thought how fortunate I was to be surrounded by so many true friends; and that it could only be in times of misfortune that we could discover them.

The King was relying more and more on my judgment. He seemed aware of the change in me and I remembered how in the beginning he had declared he would never allow a woman to advise him. We had both changed.

But there was one quality in him which never altered—that unnatural calm. It almost seemed that he lacked interest in his own affairs.

I heard (me of his ministers say that to discuss affairs with him made him feel that be was discussing matters concerning the Emperor of China instead of the King of France.

For this reason I found myself being drawn more and more into affairs.

I had tried to keep out of them, but Mercy had warned me that if I did not play a part in them no one would. Someone must be at the helm of a ship which was being buffeted by a fierce storm. This was said by Mirabeau, who, now that Orleans was no longer in France, was the one man who could hold back the revolution.

That man was right. He was brilliant, I knew. Mercy wrote of him often; Axel spoke of him. He was a rascal, said Axel, and-we should not trust him; but at this time he was the most important man in France and we should not ignore him.

It was noticed that I was taking a part in affairs. The King would never agree to anything without, as he openly said, ‘consulting the Queen. ” The new person I had become, although ignorant of much, at least had a firm opinion on what should be done, and this was better than the attitude of the King, which was never the same for two days running. I was for standing firm against the revolutionaries. We had conceded enough, I declared. We should concede no more. Axel confirmed me in my opinions. Perhaps I drew on him for them. He was not only my lover; he was my adviser; and the fact that he and Mercy were in agreement on so many points pleased me.

Mirabeau began to change his mind. He now remarked:

“The King has only one man with him—his wife.”

And this meant that Mirabeau considered me a greater power in France than the King.

“When one undertakes to direct a revolution,” Mirabeau was reported to me as having said, “the difficulty is not to spur it on but restrain it.”

I gathered from that remark that he wished to restrain it.

In February my brother Joseph died. I felt numbed when I read the letter from Leopold, who had succeeded him. There had been a bond between Joseph and myself, although his criticism had irritated me; but I realised now that he had meant to help me, and how much wisdom there had been behind his comments.

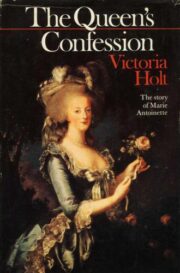

"The Queen`s Confession" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen`s Confession". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen`s Confession" друзьям в соцсетях.