What a thrill to enter that great gleaming edifice! Bertie held her hand and Vicky clung to her father’s. It was magical! The flowers and the fountains were beautiful. The organ was playing triumphant music and there was an orchestra with two hundred instruments and six hundred singers. When the music stopped the cheers broke out. Cheers for Albert. This was far more magnificent even than the coronation, and Victoria was deeply moved because it was Albert’s creation.

The orchestra began to play God Save the Queen and the tears were in Victoria’s eyes as she listened to those loyal voices. She then declared the Exhibition open. The trumpets sounded and the cheering was deafening.

How much happier was such a peace festival than these foolish riots which had been tormenting the country for some time, and worse still the fearful revolutions of Europe.

Everyone was loud in their praises of the exhibits and the wonderful Crystal Palace with its flowers and statues. The Queen had a word with Paxton, whose genius, guided by Albert, was responsible for the brilliant array. It was particularly wonderful that he had begun his career as a common garden boy.

The old Duke of Wellington put in an appearance. He was eighty-seven on that day and because Arthur had been born on his birthday the Duke had been one of his godparents. He asked permission to call at the palace later as he had some toys and a gold cup for Arthur and the Queen told him that he would be most welcome – not only by the fortunate Arthur who was to be the recipient of such gifts but by them all.

Oh, that was a happy day! To see Albert vindicated gave the Queen the greatest pleasure. She could even be charming to Lord Palmerston when he visited the Exhibition.

‘Is it not a wonderful conception, Lord Palmerston?’ she asked; and even he could find no fault with anything.

What a pleasure to return tired but happy to the palace to receive the Duke of Wellington when he called; and little Arthur, his namesake, was ready with a nosegay of flowers to present to his godfather.

And then to Covent Garden to see The Huguenots and be cheered by the audience.

When at last the day was over and the Queen and Albert were alone she said to him, ‘This is the proudest and happiest day of my happy life.’

Hardly a day passed without the Queen’s visiting the Exhibition. She greatly admired every section and made a great effort to understand the exhibits of machinery when they were explained to her. She drank in all the praise – and now everyone was praising. Royal relations came from overseas to see the wonders of which they had heard so much and among them the Prince and Princess of Prussia, with their son Frederick, who was known as Fritz – a charming young man. Albert was very interested in him because he would one day be the King of Prussia and Albert had set his heart on Vicky’s mounting that throne. If Vicky could not be Queen of England – and that throne must go to Bertie – then Prussia was the next best thing.

Prince Fritz found the Exhibition fascinating and, like the Queen, visited it frequently. He was ten years older than eleven-year-old Vicky so put himself in charge of her, Bertie, Alice and Alfred when they walked round the stands. He was most impressed by the intelligent questions Vicky asked; the others would often stroll off and leave them talking together.

It was the same in the gardens of the palace, Fritz and Vicky often walked together. Victoria and Fritz’s mother were fully aware of this. ‘Of course,’ said the Queen fondly, ‘Vicky is old for her age.’

‘And there is no doubt that Fritz is taken with her.’

‘If he should continue to be …’ The mothers smiled at each other knowingly. The Queen had no qualms; she knew it was just what Albert was hoping for.

At the end of July the family went to Osborne for the heat of the summer, and this, as summer always did, passed too quickly. The Exhibition was to be closed on the 15th of October. The Queen had chosen this date because it was the anniversary of the day she and Albert had become betrothed.

On the 14th she paid her last visit to the Exhibition. It was so moving, particularly when the music played on the Sommerophone, an enormous brass instrument named after the man who had invented it, but of course sad to see the workmen already dismantling Albert’s wonderful creations.

The next day it poured with rain and was, as the Queen said, appropriately wretched. She did not attend the closing ceremony as Albert had said that would not be fitting, so he went alone.

She was delighted to receive a letter from the Prime Minister in which he said:

The grandeur of the conception, the zeal, invention and talent displayed in the execution, and the perfect order maintained from the first day to the last, have contributed together to give imperishable fame to Prince Albert.

The Queen wept with joy when she read those words. Nothing, she declared, could have given her greater pleasure.

Chapter XXI

DEATHS AND BIRTH

The arrival of the Hungarian General Kossuth in October gave the Queen an opportunity for which she had long waited. Kossuth had endeavoured to free his country from the Austrian yoke and failing to do so had been obliged to escape to Turkey. While there he had decided that he would settle in America and the Americans had sent a frigate to convey him to his future home. On the way he called at Southampton where he was given a great welcome. He decided that he would like to see a little of England and did so, and because of his notorious bravery he was acclaimed wherever he went.

Victoria was uneasy. She admitted that Kossuth was brave; but he was a rebel who had been in revolt against his rulers. How could the Monarchy smile on that sort of behaviour? It would be an encouragement to the troublemakers in places like Ireland to rise up against their sovereign.

When she heard that Lord Palmerston admired Kossuth and was going to receive him she was furious and sent for Lord John Russell.

‘I hear that Lord Palmerston is planning to receive Kossuth in his house,’ she said.

Lord Russell said that that was unfortunately so.

‘I have told him that it is unwise,’ said the Prime Minister, ‘but he replies that he will not be told whom he shall invite as guests to his own house.’

‘I will dismiss him if he receives Kossuth,’ replied Victoria. ‘I shall bring such pressure to bear that this is done.’

Lord Russell reported to Palmerston who, with his usual nonchalance, decided that after all he would not receive Kossuth.

The Queen laughed with Albert. ‘He becomes more and more despicable,’ she declared.

Another opportunity followed almost immediately, through relations with France. Louis Napoleon, the nephew of the great Napoleon, President of the Republic, arrested several members of the government and dissolving the Council of State and the National Assembly set himself up as Emperor Napoleon III.

The Queen was horrified. Members of the French royal family were in exile in England and hoping that the Monarchy would be restored; this would be a blow to all their hopes.

She was delighted when Lord John called to tell her that the Cabinet had decided at a meeting called to discuss these matters that a policy of non-interference had been decided on. But Lord Palmerston was a law unto himself. Calling on the French Ambassador in London he told him that he did not see how Louis Napoleon could have acted otherwise and this, coming from the Foreign Secretary, could only mean that the new Emperor could hope for British recognition.

This was too much, not only for the Queen but for the Cabinet. The Queen declared that Palmerston must be dismissed without preamble, but Lord John Russell advised caution.

Lord John Russell presents his humble duty to Your Majesty. Since writing to Your Majesty this morning it has occurred to him that it would be best that Your Majesty should not give any commands to Lord Palmerston on his sole advice. With this view he has summoned the Cabinet for Monday and he humbly proposes that Your Majesty should await their advice.

Lord Palmerston when called to task tried to bluff his way out of the situation but he did not succeed in his usual manner. He answered that he was entitled to personal opinions and his attitude to the new Emperor was a matter of his own private feelings.

This was unacceptable and Palmerston was asked to resign.

In the midst of all this came news from Hanover that the King – Uncle Cumberland – had died. Strangely enough the Queen was shocked by the news. All her life this man had been the wicked uncle. In her childhood many had believed that he had tried to have her removed to make his way clear to the throne; and afterwards he had caused a great deal of trouble. Now he was dead and his poor blind son George was succeeding him. She could not help being saddened. Death was relentless. So recently they had lost poor dear Aunt Louise and she knew that Uncle Leopold mourned her deeply, as she did herself.

She was fortunate, she reminded herself. Her children were all healthy and so many of her family lost their babies or were unable to produce them like poor Aunt Adelaide, who had died recently.

But to return to Palmerston; this was great good fortune. Lord John and his colleagues decided that the Foreign Secretary had violated the confidence of his colleagues and was unsuitable for his office. To the Queen’s delight even he could find no alternative to resignation and Lord Granville was appointed Foreign Secretary.

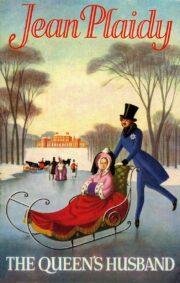

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.