Chapter XXVI

BERTIE’S PROGRESS

With Vicky married the pressing problem was the future of the Prince of Wales.

‘Ah,’ sighed Albert, ‘if only Bertie had half the brains of his sister!’

‘The trouble with Bertie is that he refuses to work,’ replied the Queen.

There were continual complaints from Mr Gibbs. Bertie would not ‘concentrate’. He seemed to ‘set up a resistance to work’. ‘Could do so much better,’ was the continual report.

Baron Stockmar, who was back in England, was consulted. People who would not work must be made to work, was his verdict, but it was not easy to whip a young man of almost seventeen into submission.

Perhaps it was time to change Bertie’s mode of education. He should no longer have a tutor but a Governor. A stern disciplinarian would be the best choice; someone who would stamp out the inherent frivolity of Bertie’s nature. A course of study should be planned for him which would give him no opportunity of wasting time.

Having mapped out a stringent course for the Prince to follow, Stockmar declared that he must return to Coburg. His health, which had always been one of his major concerns, and the care of which had given him great enjoyment, was failing fast and he felt he must go back to his family to be nursed.

When Bertie heard that the old man was going, he was wild with joy. His immediate reaction was to seize Alice and dance round the room with her.

‘You had better not let Papa see you do that,’ she warned.

‘What does it matter? Everything I do is wrong in Papa’s eyes, so this can’t be much worse than anything else.’

He would no longer have those cold eyes on him criticising everything he did, planning great working programmes (to complete which satisfactorily he would have to be a mathematician, theologian, historian and goodness knows what else), commenting on the way he did everything, discovering that he had a violent temper (what about Mama’s?) and that he was in every way an unsatisfactory person.

It was all really a waste of time because his parents knew that already. But lots of people did not think so. His sisters and brothers for instance; some of the members of the household too, and old Lord Palmerston had winked at him once when his mother was telling him how her eldest son had failed to do this or that; and he had heard the Prime Minister say that he was of the opinion that the Prince of Wales was a very intelligent young man.

But of course it was those in authority over him who counted and it was very pleasant to contemplate that the disagreeable old Baron was about to depart.

Bertie watched him go with great glee while his parents wept and embraced the old fellow and told him how they would miss him. He must write regularly, said Albert; which made Bertie groan inwardly for he realised that Stockmar could be a menace from afar. Still he could do less harm in Coburg than in Buckingham Palace and Bertie had learned to be grateful for small mercies.

His seventeenth birthday arrived. Surely a day for celebrations. But not for him, it seemed; there on the table was a long account of the changes which would be taking place in his life. Mr Gibbs was going and Colonel Bruce was replacing him. The Colonel was known as a martinet and Bertie would have to report to him before he even left the palace; it would be like being under military command without any of the fun of being in the Army.

The long list of requirements ended with the words: ‘Life is composed of duties. You will have to be taught what you may and may not do.’

Bertie was experienced enough to see that he was jumping out of an irritatingly restricting frying-pan into fire which was planned to envelope him like a straitjacket.

As if they had not enough to worry them without Bertie’s intransigence there was trouble as ever at home and abroad. When Orsini had attempted to assassinate the French Emperor and Empress and it was discovered that the grenades had been manufactured and the plot hatched in England, a great wave of hostility swept across France towards their new ally. To placate them Palmerston introduced a bill making it a felony to conspire to murder and on this the government was defeated and Lord Derby, with his henchman Mr Disraeli, returned to office. Orsini was executed in Paris but one of his confederates, tried in London, was acquitted. An uneasy situation prevailed between England and France which was so disappointing after the great friendship the Queen had felt for the charming little Emperor and his beautiful wife.

The Derby Ministry was of short duration. When they tried to introduce an amendment to the Reform Bill they were defeated. A new difficulty presented itself when both Lord John Russell and Lord Palmerston were contending for the premiership and the Queen had no alternative but to send for Lord Granville. Fortunately he was unable to form a ministry and very soon Lord Palmerston, having suceeded in doing so, was back at the helm.

‘It is comforting to know that we have a strong man at the head of affairs,’ said the Queen.

But there was no real comfort.

Almost immediately after her marriage Vicky had become pregnant.

In the midst of all this political activity the Queen’s mind was constantly with her daughter. No sooner had she discovered that she was pregnant than she was writing long letters of advice. She commiserated with Vicky, saying that now that Vicky had actually experienced marriage they could talk frankly as two women. Vicky was very quick to experience the ‘shadow side’ of the relationship between the sexes. It was wonderful to have children, and although they were quite ugly at birth they quickly grew charming (she must tell Vicky the latest sayings of Baby Beatrice who was a great comfort to them just now) but at the actual birth human dignity was lost and women were more like cows or dogs and their poor nature became quite animal.

Stockmar wrote protesting that the Queen’s spate of letters was worrying the Princess. It was true that Vicky had a great deal to contend with. The schloss to which Fritz had taken her was very ancient, said to be haunted and bitterly cold; hot water had to be carried in buckets through draughty corridors to the bedrooms and was tepid by the time it reached them; there was some suspicion of the foreigner within their midst and although Fritz was kind and easy-going, Vicky missed home, particularly her father.

There was bickering between Victoria and Albert because of Stockmar’s criticisms and Victoria retaliated by saying that Stockmar was an interfering old man.

Three months after Vicky had left England Albert decided that he must see her and paid a visit to Berlin. He spent only three days with his daughter but it was comforting to see that she was well and as happy as she could be in the circumstances.

When he returned Victoria said that while she had been waiting for his return she had decided that next time she would accompany him. She was longing to see Vicky and she thought they might go again together in August.

This they did and it was wonderful to see the beloved child again. The Queen wanted to carry her daughter off for cosy chats about how she should look after herself and discussions on the baby’s arrival which were far from cosy.

‘How I wish I could be here when the baby is born!’ she cried. ‘It is a mother’s privilege to be with her daughter at such a time. Alas, I have to remember that I am the Queen.’

Vicky smiled in the old mischievous way and retorted: ‘Well, Mama, as Papa says, you are the last one to forget that.’

But it was different talking with a young married woman from talking with a daughter whom one felt one had always to correct.

Vicky confessed to her that she had always loved her dearly, but she had been very naughty at times and disobedient, she knew. She had been thinking since the parting that because of this her mother might not think she loved her as much as she did.

‘All children can be naughty,’ said the Queen fondly.

‘Then you understand, Mama?’

‘Perfectly!’ declared the Queen happily. ‘Perhaps I didn’t behave always as I should. That temper of mine would burst out. And I always felt that you children came between me and your father, and the greatest joy in my life was to be alone with him. You must understand that now that you have Fritz.’

Vicky said she could understand her mother’s feeling for dearest Papa. ‘Papa is an angel,’ she added.

Victoria wept with pleasure. It was wonderful to think that her daughter had such understanding.

She was eagerly looking forward to the birth of her grandchild, she said, but Vicky must do everything her mother said. She would send a list of instructions.

‘Oh, my darling,’ she cried, ‘how willingly would I bear your suffering for you.’

In January – a year after Vicky’s wedding – her child was born. The birth was protracted and Vicky suffered far more than her mother ever had. At one time her life and that of the child were in danger. Fortunately the Queen and Albert did not know of this until the danger had passed.

Then they heard that Vicky had a son; he was to be called Wilhelm.

Bertie’s worst fears were realised. He was practically Colonel Bruce’s prisoner. He could not leave his apartments without his Governor’s wanting to know where he was going and any sharp retort or the slightest protest would be reported to his parents. He must conform to the diet prepared for him; he was to have three meals a day at precisely the time laid down for them in the rules; and as Prince Albert did not believe in self-indulgence in any form, these meals must be light. Pudding might be served but it would be wiser not to take it or if the Prince of Wales did take it, it must be a small helping.

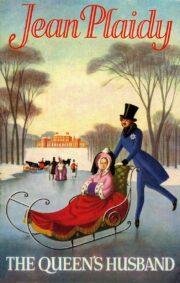

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.