Albert could always handle her. She saw his point. While she had him, she said, she had everything to live for.

She became gay again. The period of mourning was over.

But, alas, Albert’s health did not improve.

Trouble came from an expected quarter.

Stockmar wrote to break news which, he said, perhaps not strictly truthfully, he would rather have kept to himself.

It was well known on the Continent that while he was at Curragh Camp the Prince of Wales had formed a liaison with an actress. This affair had gone as far as it was possible for such an affair to go. It seemed as though the Prince of Wales was fulfilling their doleful prophecies.

When Albert read the letter his first thought was: The Queen must not know.

She would be horribly shocked; this might bring on that dangerous mood of depression. He must if possible keep this from her.

What could he do to a young man of nineteen? He thought of his brother Ernest and the evil which had befallen him. Bertie, it seemed, was going to be such another.

He must go to Cambridge and see Bertie. He must discover the truth of this matter. He had a streaming cold and he could feel the fever in his body; his frequent shivering was a warning, but it was his duty to go to Cambridge and when had he ever shirked his duty?

The weather was bleak, cold and damp, and although the symptoms which were affecting him warned him that he should stay in bed, he went off to Cambridge.

When Bertie saw how ill his father looked he was immediately contrite. He spoke naturally and without the embarrassment he usually felt in his father’s presence.

‘Oh, Papa, you shouldn’t have come in this weather.’

Albert looked at him sadly. ‘My son,’ he said, ‘it was my duty to come. You will know why, when I tell you I am aware of your conduct at the Curragh Camp.’

Bertie flushed scarlet.

‘You may well be ashamed,’ said his father. ‘I confess I could scarcely believe it even of you. How could you behave in such a way?’

Bertie stammered that it was not really such an unusual way to behave. Other fellows …

‘Other fellows! You are not other fellows. You are the heir to the throne.’

Bertie cast down his eyes. He wanted to shout at his father that he was tired of being treated like a child; they couldn’t go on robbing him of his freedom all his life. When he was twenty-one, he would show them.

But his father looked so ill. He had never seen him quite like this. His face was such a strange colour and the shadows under his eyes so deep; his eyes were unnaturally bright too.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Bertie.

Albert nodded. ‘I believe you are,’ he replied with a faint smile. Some of the reforming fire had gone out of him. He felt utterly weary and longed for his bed.

‘Bertie,’ he said, ‘I want you to realise your responsibilities.’

‘I do,’ said Bertie.

‘I want you to act in a way that will show that you do.’

Bertie’s kind heart was touched by the pitiful looks of his father. He wanted to end this interview as quickly as possible so that his father could get back home and to bed where he obviously should be.

‘I will try to in future,’ he said. ‘Papa, you are not well. You should be in bed.’

Albert held up a hand that was not quite steady.

‘If you would mend your ways, try not to make your mother so anxious, remember that one day you will be King of England …’

‘I will, Papa.’

Albert nodded. He did not love his son; he could never do that; but he did not feel that mild resentment and faint dislike which he had felt before.

‘Bertie,’ he said, ‘I shall say nothing to your mother of this affair.’

‘Thank you, Papa.’

Albert rose.

‘You are going home now, Papa?’ asked Bertie.

Albert nodded.

‘You should be in bed.’

Albert smiled. It was the first time his son had ever told him what he should do. In the circumstances it touched him.

When he returned to the palace it was clear that he was ill. The Queen was worried and scolded him for going out in such awful weather.

‘I had to go,’ he said wearily.

‘What on earth could be so important as to make you?’ she demanded.

He said nothing and seeing how weary he was she stopped scolding and helped him to bed. She sat beside it watching him, holding his hand.

‘You’ll soon be well, Albert,’ she said. ‘I am going to insist on your taking greater care.’

He was a little better next morning and would not stay in bed; he sat in the bedroom in his padded dressing-gown with its scarlet velvet collar and went through state papers; but he could eat very little and the Queen was growing very anxious.

Sir James Clark was a little concerned. His colleague Dr Baly, the other royal physician, had been killed only a short while before in a railway accident. Sir James, never very sure of himself, now wished to call in further advice and suggested Dr Jenner, who was an expert on typhoid fever.

When Dr Jenner came and examined Albert it was his opinion that, although Albert was not a victim of the fever, there were signs that he might be affected by the germs. They must therefore prepare themselves for an attack of this dreaded disease.

When the Queen heard this she was terrified. People died of typhoid fever.

‘The Prince would have every possible care,’ said Sir James. ‘And so far he does not have typhoid fever.’

Albert insisted on sleeping in a small bed at the foot of their big bed.

‘I toss and turn so much that I should disturb you,’ he said.

‘Disturb me!’ cried the Queen. ‘Do you think I shall have any sleep? I would be afraid to sleep in any case. You might need me.’

She was up and down all night giving him cooling drinks.

‘If I get this fever,’ he said, ‘I shall die.’

‘You will not die!’ she commanded. And he smiled at her. ‘Dearest little wife,’ he said, ‘I do not fear death. I only think of how you will miss me and how sad you will be.’

‘Oh, Albert, don’t. I can’t bear it. You are my life. How could I go on if you were not here?’

‘You must, dearest, you must.’

‘I’ll not have this talk,’ she cried. ‘You are here with me, and here you are going to stay. You haven’t got the fever. You’re not going to have it.’

‘No,’ he said, to soothe her, ‘no.’ And he thought: Poor Victoria. Poor little Queen.

For five nights he tossed and turned in his little bed. She had scarcely slept at all. The Queen was desperate because he would not eat. When she tried to tempt him with a little soup, he only shook his head.

One day he seemed a little better and the Queen asked if he would like Alice to read to him. Vicky used to and when she had gone Alice took on the duty. He brightened a little. But when she came and started Silas Marner he shook his head. He didn’t like it. She tried others but he did not want to listen to anything.

The Queen said brightly: ‘We’ll try Sir Walter Scott tomorrow, Papa dear.’

Albert smiled at her wanly.

Then he became irritable.

‘I believe it’s a good sign,’ cried the Queen jubilantly.

His complaints were peevish, which was not like him. The Albert Victoria had known seemed to be replaced by a wild-eyed man.

Alice read to him again and he seemed to enjoy that for a little while.

‘That’s a good sign,’ said the Queen. ‘More like dear good blessed Papa.’

But a few hours later when she was sitting by his bed he said suddenly: ‘Can you hear the birds singing?’

She could not and he added: ‘When I heard them I thought I was at Rosenau.’

She went out of the room because she could not control her sobbing. She knew that he was very ill.

Dr Jenner wanted to talk to her. She looked at him anxiously.

‘Your Majesty knows that all along we have feared … gastric fever.’

Gastric fever! Bowel fever! She knew that these were kinder names for the dreaded typhoid.

‘I know it,’ she said. ‘And now …?’

‘I am afraid that this is what His Highness is now suffering from.’

She felt dazed. Typhoid! The dreaded killer!

‘Vicky,’ he said, ‘Vicky.’

For a moment she thought that he was speaking to her, then she realised that he thought she was their daughter.

‘Vicky is well, my darling,’ she said. ‘Vicky is in Berlin with her husband.’

He nodded. Alice sat on the other side of the bed.

He looked at her and was suddenly lucid. He remembered that Vicky was pregnant again and that he was worried about her.

‘Did you write to Vicky?’

‘Yes, dear Papa.’

‘Did you tell her how I was?’

‘I told her that you were ill, Papa.’

He shook his head.

‘You should have told her that I am dying,’ he said.

All the children were there. Bertie oddly enough was her greatest comfort.

‘Oh, Bertie, what am I going to do?’

‘I will care for you, Mama.’

‘But he will get better. The doctors have been telling me. They never despair with fever. People get over it … often.’

‘Yes, Mama. He has every care. You must take care of yourself.’

‘I tried to take care of him. He would go off. That awful November day he went off because he felt it was his duty. I never quite knew where he went. He was in such a hurry. He said it was so important and when he came back he was too ill to say anything. We could only think of getting him to bed. I’ll never forgive those people who asked him to go wherever he went …’

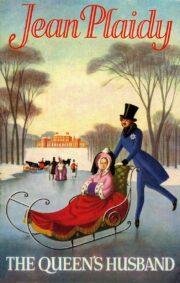

"The Queen’s Husband" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Queen’s Husband". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Queen’s Husband" друзьям в соцсетях.