“You ought to feel the warmth of the real south,” said Justine. “A hundred and fifteen in the shade, if you can find any.”

“No wonder you don’t feel the heat.” He laughed the soundless laugh, as always; a hangover from the old days, when to laugh aloud might have tempted fate. “And the heat would account for the fact that you’re hard-boiled.”

“Your English is colloquial, but American. I would have thought you’d have learned English in some posh British university.”

“No. I began to learn it from Cockney or Scottish or Midlands tommies in a Belgian camp, and didn’t understand a word of it except when I spoke to the man who had taught it to me. One said ‘abaht,’ one said ‘aboot,’ one said ‘about,’ but they all meant ‘about.’ So when I got back to Germany I saw every motion picture I could, and bought the only records available in English, records made by American comedians. But I played them over and over again at home, until I spoke enough English to learn more.”

Her shoes were off, as usual; awed, he had watched her walk barefooted on pavements hot enough to fry an egg, and over stony places.

“Urchin! Put your shoes on.”

“I’m an Aussie; our feet are too broad to be comfortable in shoes. Comes of no really cold weather; we go barefoot whenever we can. I can walk across a paddock of bindy-eye burns and pick them out of my feet without feeling them,” she said proudly. “I could probably walk on hot coals.” Then abruptly she changed the subject. “Did you love your wife, Rain?”

“No.”

“Did she love you?”

“Yes. She had no other reason to marry me.”

“Poor thing! You used her, and you dropped her.”

“Does it disappoint you?”

“No, I don’t think so. I rather admire you for it, actually. But I do feel very sorry for her, and it makes me more determined than ever not to land in the same soup she did.”

“Admire me?” His tone was blank, astonished.

“Why not? I’m not looking for the things in you she undoubtedly did, now am I? I like you, you’re my friend. She loved you, you were her husband.”

“I think, Herzchen,” he said a little sadly, “that ambitious men are not very kind to their women.”

“That’s because they usually fall for utter doormats of women, the ‘Yes, dear, no, dear, three bags full, dear, and where would you like it put?’ sort. Hard cheese all round, I say. If I’d been your wife, I’d have told you to go pee up a rope, but I’ll bet she never did, did she?”

His lips quivered. “No, poor Annelise. She was the martyr kind, so her weapons were not nearly so direct or so deliciously expressed. I wish they made Australian films, so I knew your vernacular. The ‘Yes, dear’ bit I got, but I have no idea what hard cheese is.”

“Tough luck, sort of, but it’s more unsympathetic.” Her broad toes clung like strong fingers to the inside of the fountain wall, she teetered precariously backward and righted herself easily. “Well, you were kind to her in the end. You got rid of her. She’s far better off without you, though she probably doesn’t think so. Whereas I can keep you, because I’ll never let you get under my skin.”

“Hard-boiled. You really are, Justine. And how did you find out these things about me?”

“I asked Dane. Naturally, being Dane he just gave me the bare facts, but I deduced the rest.”

“From your enormous store of past experience, no doubt. What a fraud you are! They say you’re a very good actress, but I find that incredible. How do you manage to counterfeit emotions you can never have experienced? As a person you’re more emotionally backward than most fifteen-year-olds.”

She jumped down, sat on the wall and leaned to put her shoes on, wriggling her toes ruefully. “My feet are swollen, dammit.” There was no indication by a reaction of rage or indignation that she had even heard the last part of what he said. As if when aspersions or criticisms were leveled at her she simply switched off an internal hearing aid. How many there must have been. The miracle was that she didn’t hate Dane.

“That’s a hard question to answer,” she said. “I must be able to do it or I wouldn’t be so good, isn’t that right? But it’s like…a waiting. My life off the stage, I mean. I conserve myself, I can’t spend it offstage. We only have so much to give, don’t we? And up there I’m not myself, or perhaps more correctly I’m a succession of selves. We must all be a profound mixture of selves, don’t you think? To me, acting is first and foremost intellect, and only after that, emotion. The one liberates the other, and polishes it. There’s so much more to it than simply crying or screaming or producing a convincing laugh. It’s wonderful, you know. Thinking myself into another self, someone I might have been, had the circumstances been there. That’s the secret. Not becoming someone else, but incorporating the role into me as if she was myself. And so she becomes me.” As though her excitement was too great to bear in stillness, she jumped to her feet. “Imagine, Rain! In twenty years’ time I’ll be able to say to myself, I’ve committed murders, I’ve suicided, I’ve gone mad, I’ve saved men or ruined them. Oh! The possibilities are endless!”

“And they will all be you.” He rose, took her hand again. “Yes, you’re quite right, Justine. You can’t spend it offstage. In anyone else, I’d say you would in spite of that, but being you, I’m not so sure.”

18

If they applied themselves to it, the Drogheda people could imagine that Rome and London were no farther away than Sydney, and that the grown-up Dane and Justine were still children going to boarding school. Admittedly they couldn’t come home for all the shorter vacations of other days, but once a year they turned up for a month at least. Usually in August or September, and looking much as always. Very young. Did it matter whether they were fifteen and sixteen or twenty-two and twenty-three? And if the Drogheda people lived for that month in early spring, they most definitely never went round saying things like, Well, only a few weeks to go! or, Dear heaven, it’s not a month since they left! But around July everyone’s step became brisker, and permanent smiles settled on every face. From the cookhouse to the paddocks to the drawing room, treats and gifts were planned.

In the meantime there were letters. Mostly these reflected the personalities of their authors, but sometimes they contradicted. One would have thought, for instance, that Dane would be a meticulously regular correspondent and Justine a scrappy one. That Fee would never write at all. That the Cleary men would write twice a year. That Meggie would enrich the postal service with letters every day, at least to Dane. That Mrs. Smith, Minnie and Cat would send birthday and Christmas cards. That Anne Mueller would write often to Justine, never to Dane.

Dane’s intentions were good, and he did indeed write regularly. The only trouble was he forgot to post his efforts, with the result that two or three months would go by without a word, and then Drogheda would receive dozens on the same mail run. The loquacious Justine wrote lengthy missives which were pure stream-of-consciousness, rude enough to evoke blushes and clucks of alarm, and entirely fascinating. Meggie wrote once every two weeks only, to both her children. Though Justine never received letters from her grandmother, Dane did quite often. He also got word regularly from all his uncles, about the land and the sheep and the health of the Drogheda women, for they seemed to think it was their duty to assure him all was truly well at home. However, they didn’t extend this to Justine, who would have been flabbergasted by it anyway. For the rest, Mrs. Smith, Minnie, Cat and Anne Mueller, correspondence went as might be expected.

It was lovely reading letters, and a burden writing them. That is, for all save Justine, who experienced twinges of exasperation because no one ever sent her the kind she desired—fat, wordy and frank. It was from Justine the Drogheda people got most of their information about Dane, for his letters never plunged his readers right into the middle of a scene. Whereas Justine’s did.

Rain flew into London today [she wrote once], and he was telling me he saw Dane in Rome last week. Well, he sees a lot more of Dane than of me, since Rome is at the top of his travel agenda and London is rock bottom. So I must confess Rain is one of the prime reasons why I meet Dane in Rome every year before we come home. Dane likes coming to London, only I won’t let him if Rain is in Rome. Selfish. But you’ve no idea how I enjoy Rain. He’s one of the few people I know who gives me a run for my money, and I wish we met more often.

In one respect Rain’s luckier than I am. He gets to meet Dane’s fellow students where I don’t. I think Dane thinks I’m going to rape them on the spot. Or maybe he thinks they’ll rape me. Hah. Only happen if they saw me in my Charmian costume. It’s a stunner, people, it really is. Sort of up-to-date Theda Bara. Two little round bronze shields for the old tits, lots and lots of chains and what I reckon is a chastity belt—you’d need a pair of tin-cutters to get inside it, anyway. In a long black wig, tan body paint and my few scraps of metal I look a smasher.

…Where was I??? Oh, yes, Rain in Rome last week meeting Dane and his pals. They all went out on the tiles. Rain insists on paying, saves Dane embarrassment. It was some night. No women, natch, but everything else. Can you imagine Dane down on his knees in some seedy Roman bar saying “Fair daffodils, we haste to see thee weep so soon away” to a vase of daffodils? He tried for ten minutes to get the words of the quotation in their right order and couldn’t, then he gave up, put one of the daffodils between his teeth instead and did a dance. Can you ever imagine Dane doing that? Rain says it’s harmless and necessary, all work and no play, etc. Women being out, the next best thing is a skinful of grog. Or so Rain insists. Don’t get the idea it happens often, it doesn’t, and I gather when it does Rain is the ringleader, so he’s along to watch out for them, the naive lot of raw prawns. But I did laugh to think of Dane’s halo slipping during the course of a flamenco dance with a daffodil.

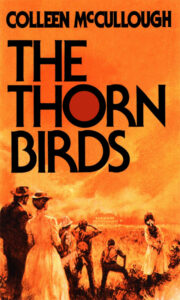

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.