“That isn’t hard to understand. I’ve never felt quite the way I did in Saint Peter’s, so what it must have been like for you I can’t imagine.”

“Oh, I think you can, somewhere inside. If you truly couldn’t, you wouldn’t be such a fine actress. But with you, Jus, it comes from the unconscious; it doesn’t erupt into thought until you need to use it.”

They were sitting on a small couch in a far corner of the room, and no one came to disturb them.

After a while he said, “I’m so pleased Frank came,” looking to where Frank was talking with Rainer, more animation in his face than his niece and nephew had ever seen. “There’s an old Rumanian refugee priest I know,” Dane went on, “who has a way of saying, ‘Oh, the poor one!’ with such compassion in his voice… I don’t know, somehow that’s what I always find myself saying about our Frank. And yet, Jus, why?”

But Justine ignored the gambit, went straight to the crux. “I could kill Mum!” she said through her teeth. “She had no right to do this to you!”

“Oh, Jus! I understand. You’ve got to try, too. If it had been done in malice or to get back at me I might be hurt, but you know her as well as I do, you know it’s neither of those. I’m going down to Drogheda soon. I’ll talk to her then, find out what’s the matter.”

“I suppose daughters are never as patient with their mothers as sons are.” She drew down the corners of her mouth ruefully, shrugged. “Maybe it’s just as well I’m too much of a loner ever to inflict myself on anyone in the mother role.”

The blue eyes were very kind, tender; Justine felt her hackles rising, thinking Dane pitied her.

“Why don’t you marry Rainer?” he asked suddenly.

Her jaw dropped, she gasped. “He’s never asked me,” she said feebly.

“Only because he thinks you’d say no. But it might be arranged.”

Without thinking, she grabbed him by the ear, as she used to do when they were children. “Don’t you dare, you dog-collared prawn! Not one word, do you hear? I don’t love Rain! He’s just a friend, and I want to keep it that way. If you so much as light a candle for it, I swear I’ll sit down, cross my eyes and put a curse on you, and you remember how that used to scare the living daylights out of you, don’t you?”

He threw back his head and laughed. “It wouldn’t work, Justine! My magic is stronger than yours these days. But there’s no need to get so worked up about it, you twit. I was wrong, that’s all. I assumed there was a case between you and Rain.”

“No, there isn’t. After seven years? Break it down, pigs might fly.” Pausing, she seemed to seek for words, then looked at him almost shyly. “Dane, I’m so happy for you. I think if Mum was here she’d feel the same. That’s all it needs, for her to see you now, like this. You wait, she’ll come around.”

Very gently he took her pointed face between his hands, smiling down at her with so much love that her own hands came up to clutch at his wrists, soak it in through every pore. As if all those childhood years were remembered, treasured.

Yet behind what she saw in his eyes on her behalf she sensed a shadowy doubt, only perhaps doubt was too strong a word; more like anxiety. Mostly he was sure Mum would understand eventually, but he was human, though all save he tended to forget the fact.

“Jus, will you do something for me?” he asked as he let her go.

“Anything,” she said, meaning it.

“I’ve got a sort of respite, to think about what I’m going to do. Two months. And I’m going to do the heavy thinking on a Drogheda horse after I’ve talked to Mum—somehow I feel I can’t sort anything out until after I’ve talked to her. But first, well… I’ve got to get up my courage to go home. So if you could manage it, come down to the Peloponnese with me for a couple of weeks, tick me off good and proper about being a coward until I get so sick of your voice I put myself on a plane to get away from it.” He smiled at her. “Besides, Jussy, I don’t want you to think I’m going to exclude you from my life absolutely, any more than I will Mum. You need your old conscience around occasionally.”

“Oh, Dane, of course I’ll go!”

“Good,” he said, then grinned, eyed her mischievously. “I really do need you, Jus. Having you bitching in my ear will be just like old times.”

“Uh-uh-uh! No obscenities, Father O’Neill!”

His arms went behind his head, he leaned back on the couch contentedly. “I am! Isn’t it marvelous? And maybe after I’ve seen Mum, I can concentrate on Our Lord. I think that’s where my inclinations lie, you know. Simply thinking about Our Lord.”

“You ought to have espoused an order, Dane.”

“I still can, and I probably will. I have a whole lifetime; there’s no hurry.”

Justine left the party with Rainer, and after she talked of going to Greece with Dane, he talked of going to his office in Bonn. “About bloody time,” she said. “For a cabinet minister you don’t seem to do much work, do you? All the papers call you a playboy, fooling around with carrot-topped Australian actresses, you old dog, you.”

He shook his big fist at her. “I pay for my few pleasures in more ways than you’ll ever know.”

“Do you mind if we walk, Rain?”

“Not if you keep your shoes on.”

“I have to these days. Miniskirts have their disadvantages; the days of stockings one could peel off easily are over. They’ve invented a sheer version of theatrical tights, and one can’t shed those in public without causing the biggest furor since Lady Godiva. So unless I want to ruin a five-guinea pair of tights, I’m imprisoned in my shoes.”

“At least you improve my education in feminine garb, under as well as over,” he said mildly.

“Go on! I’ll bet you’ve got a dozen mistresses, and undress them all.”

“Only one, and like all good mistresses she waits for me in her negligee.”

“Do you know, I believe we’ve never discussed your sex life before? Fascinating! What’s she like?”

“Fair, fat, forty and flatulent.”

She stopped dead. “Oh, you’re kidding me,” she said slowly. “I can’t see you with a woman like that.”

“Why not?”

“You’ve got too much taste.”

“Chacun à son goût, my dear. I’m nothing much to look at, myself—why should you assume I could charm a young and beautiful woman into being my mistress?”

“Because you could!” she said indignantly. “Oh, of course you could!”

“My money, you mean?”

“Not, not your money! You’re teasing me, you always do! Rainer Moerling Hartheim, you’re very well aware how attractive you are, otherwise you wouldn’t wear gold medallions and netting shirts. Looks aren’t everything—if they were, I’d still be wondering.”

“Your concern for me is touching, Herzchen.”

“Why is it that when I’m with you I feel as if I’m forever running to catch up with you, and I never do?” Her spurt of temper died; she stood looking at him uncertainly. “You’re not serious, are you?”

“Do you think I am?”

“No! You’re not conceited, but you do know how very attractive you are.”

“Whether I do or not isn’t important. The important thing is that you think I’m attractive.”

She was going to say: Of course I do; I was mentally trying you on as a lover not long ago, but then I decided it wouldn’t work, I’d rather keep on having you for my friend. Had he let her say it, he might have concluded his time hadn’t come, and acted differently. As it was, before she could shape the words he had her in his arms, and was kissing her. For at least sixty seconds she stood, dying, split open, smashed, the power in her screaming in wild elation to find a matching power. His mouth—it was beautiful! And his hair, incredibly thick, vital, something to seize in her fingers fiercely. Then he took her face between his hands and looked at her, smiling.

“I love you,” he said.

Her hands had gone up to his wrists, but not to enclose them gently, as with Dane; the nails bit in, scored down to meat savagely. She stepped back two paces and stood rubbing her arm across her mouth, eyes huge with fright, breasts heaving.

“It couldn’t work,” she panted. “It could never work, Rain!”

Off came the shoes; she bent to pick them up, then turned and ran, and within three seconds the soft quick pad of her feet had vanished. Not that he had any intention of following her, though apparently she had thought he might. Both his wrists were bleeding, and they hurt. He pressed his handkerchief first to one and then to the other, shrugged, put the stained cloth away, and stood concentrating on the pain. After a while he unearthed his cigarette case, took out a cigarette, lit it, and began to walk slowly. No one passing by could have told from his face what he felt. Everything he wanted within his grasp, reached for, lost. Idiot girl. When would she grow up? To feel it, respond to it, and deny it.

But he was a gambler, of the win-a-few, lose-a-few kind. He had waited seven long years before trying his luck, feeling the change in her at this ordination time. Yet apparently he had moved too soon. Ah, well. There was always tomorrow—or knowing Justine, next year, the year after that. Certainly he wasn’t about to give up. If he watched her carefully, one day he’d get lucky.

The soundless laugh quivered in him; fair, fat, forty and flatulent. What had brought it to his lips he didn’t know, except that a long time ago his ex-wife had said it to him. The four F’s, describing the typical victim of gallstones. She had been a martyr to them, poor Annelise, even though she was dark, skinny, fifty and as well corked as a genie in a bottle. What am I thinking of Annelise for, now? My patient campaign of years turned into a rout, and I can do no better than poor Annelise. So, Fräulein Justine O’Neill! We shall see.

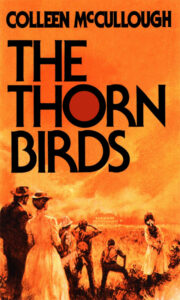

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.