“I’m not giving up acting!” she said aggressively.

“Verfluchte Kiste, did I ask you to? Grow up, Justine! Anyone would think I was condemning you to a life sentence over a sink and stove! We’re not exactly on the breadline, you know. You can have as many servants as you want, nannies for the children, whatever else is necessary.”

“Erk!” said Justine, who hadn’t thought of children.

He threw back his head and laughed. “Oh, Herzchen, this is what’s known as the morning after with a vengeance! I’m a fool to bring up realities so soon, I know, but all you have to do at this stage is think about them. Though I give you fair warning—while you’re making your decision, remember that if I can’t have you for my wife, I don’t want you at all.”

She threw her arms around him, clinging fiercely. “Oh, Rain, don’t make it so hard!” she cried.

Alone, Dane drove his Lagonda up the Italian boot, past Perugia, Firenze, Bologna, Ferrara, Padova, better by-pass Venezia, spend the night in Trieste. It was one of his favorite cities, so he stayed on the Adriatic coast a further two days before heading up the mountain road to Ljubljana, another night in Zagreb. Down the great Sava River valley amid fields blue with chicory flowers to Beograd, thence to Nis, another night. Macedonia and Skopje, still in crumbling ruins from the earthquake two years before; and Tito-Veles the vacation city, quaintly Turkish with its mosques and minarets. All the way down Yugoslavia he had eaten frugally, too ashamed to sit with a great plate of meat in front of him when the people of the country contented themselves with bread.

The Greek border at Evzone, beyond it Thessalonika. The Italian papers had been full of the revolution brewing in Greece; standing in his hotel bedroom window watching the bobbing thousands of flaming torches moving restlessly in the darkness of a Thessalonika night, he was glad Justine had not come.

“Pap-an-dre-ou! Pap-an-dre-ou! Pap-an-dre-ou!” the crowds roared, chanting, milling among the torches until after midnight.

But revolution was a phenomenon of cities, of dense concentrations of people and poverty; the scarred countryside of Thessaly must still look as it had looked to Caesar’s legions, marching across the stubble-burned fields to Pompey at Pharsala. Shepherds slept in the shade of skin tents, storks stood one-legged in nests atop little old white buildings, and everywhere was a terrifying aridity. It reminded him, with its high clear sky, its brown treeless wastes, of Australia. And he breathed of it deeply, began to smile at the thought of going home. Mum would understand, when he talked to her.

Above Larisa he came onto the sea, stopped the car and got out. Homer’s wine-dark sea, a delicate clear aquamarine near the beaches, purple-stained like grapes as it stretched to the curving horizon. On a greensward far below him stood a tiny round pillared temple, very white in the sun, and on the rise of the hill behind him a frowning Crusader fortress endured. Greece, you are very beautiful, more beautiful than Italy, for all that I love Italy. But here is the cradle, forever.

Panting to be in Athens, he pushed on, gunned the red sports car up the switchbacks of the Domokos Pass and descended its other side into Boeotia, a stunning panorama of olive groves, rusty hillsides, mountains. Yet in spite of his haste he stopped to look at the oddly Hollywoodish monument to Leonidas and his Spartans at Thermopylae. The stone said: “Stranger, go tell the Spartans that here we lie, in obedience to their command.” It struck a chord in him, almost seemed to be words he might have heard in a different context; he shivered and went on quickly.

In melted sun he paused for a while above Kamena Voura, swam in the clear water looking across the narrow strait to Euboea; there must the thousand ships have sailed from Aulis, on their way to Troy. It was a strong current, swirling seaward; they must not have had to ply their oars very hard. The ecstatic cooings and strokings of the ancient black-garbed crone in the bathhouse embarrassed him; he couldn’t get away from her fast enough. People never referred to his beauty to his face anymore, so most of the time he was able to forget it. Delaying only to buy a couple of huge, custard-filled cakes in the shop, he went on down the Attic coast and finally came to Athens as the sun was setting, gilding the great rock and its precious crown of pillars.

But Athens was tense and vicious, and the open admiration of the women mortified him; Roman women were more sophisticated, subtle. There was a feeling in the crowds, pockets of rioting, grim determination on the part of the people to have Papandreou. No, Athens wasn’t herself; better to be elsewhere. He put the Lagonda in a garage and took the ferry to Crete.

And there at last, amid the olive groves, the wild thyme and the mountains, he found his peace. After a long bus ride with trussed chickens screeching and the all-pervasive reek of garlic in his nostrils, he found a tiny white-painted inn with an arched colonnade and three umbrellaed tables outside on the flagstones, gay Greek bags hanging festooned like lanterns. Pepper trees and Australian gum trees, planted from the new South Land in soil too arid for European trees. The gut roar of cicadas. Dust, swirling in red clouds.

At night he slept in a tiny cell-like room with shutters wide open, in the hush of dawn he celebrated a solitary Mass, during the day he walked. No one bothered him, he bothered no one. But as he passed the dark eyes of the peasants would follow him in slow amazement, and every face would crease deeper in a smile. It was hot, and so quiet, and very sleepy. Perfect peace. Day followed day, like beads slipping through a leathery Cretan hand.

Voicelessly he prayed, a feeling, an extension of what lay all through him, thoughts like beads, days like beads. Lord, I am truly Thine. For Thy many blessings I thank Thee. For the great Cardinal, his help, his deep friendship, his unfailing love. For Rome and the chance to be at Thy heart, to have lain prostrate before Thee in Thine own basilica, to have felt the rock of Thy Church within me. Thou hast blessed me above my worth; what can I do for Thee, to show my appreciation? I have not suffered enough. My life has been one long, absolute joy since I began in Thy service. I must suffer, and Thou Who suffered will know that. It is only through suffering that I may rise above myself, understand Thee better. For that is what this life is: the passage toward understanding Thy mystery. Plunge Thy spear into my breast, bury it there so deeply I am never able to withdraw it! Make me suffer… For Thee I forsake all others, even my mother and my sister and the Cardinal. Thou alone art my pain, my joy. Abase me and I shall sing Thy beloved Name. Destroy me, and I shall rejoice. I love Thee. Only Thee…

He had come to the little beach where he liked to swim, a yellow crescent between beetling cliffs, and stood for a moment looking across the Mediterranean to what must be Libya, far below the dark horizon. Then he leaped lightly down the steps to the sand, kicked off his sneakers, picked them up, and trod through the softly yielding contours to the spot where he usually dropped shoes, shirt, outer shorts. Two young Englishmen talking in drawling Oxford accents lay like broiling lobsters not far away, and beyond them two women drowsily speaking in German. Dane glanced at the women and self-consciously hitched his swimsuit, aware they had stopped conversing and had sat up to pat their hair, smile at him.

“How goes it?” he asked the Englishmen, though in his mind he called them what all Australians call the English, Pommies. They seemed to be fixtures, since they were on the beach every day.

“Splendidly, old boy. Watch the current—it’s too strong for us. Storm out there somewhere.”

“Thanks.” Dane grinned, ran down to the innocently curling wavelets and dived cleanly into shallow water like the expert surfer he was.

Amazing, how deceptive calm water could be. The current was vicious, he could feel it tugging at his legs to draw him under, but he was too strong a swimmer to be worried by it. Head down, he slid smoothly through the water, reveling in the coolness, the freedom. When he paused and scanned the beach he saw the two German women pulling on their caps, running down laughing to the waves.

Cupping his hands around his mouth, he called to them in German to stay in shallow water because of the current. Laughing, they waved acknowledgment. He put his head down then, swam again, and thought he heard a cry. But he swam a little farther, then stopped to tread water in a spot where the undertow wasn’t so bad. There were cries; as he turned he saw the women struggling, their twisted faces screaming, one with her hands up, sinking. On the beach the two Englishmen had risen to their feet and were reluctantly approaching the water.

He flipped over onto his belly and flashed through the water, closer and closer. Panicked arms reached for him, clung to him, dragged him under; he managed to grip one woman around the waist long enough to stun her with a swift clip on the chin, then grabbed the other by the strap of her swimsuit, shoved his knee hard into her spine and winded her. Coughing, for he had swallowed water when he went under, he turned on his back and began towing his helpless burdens in.

The two Pommies were standing shoulder-deep, too frightened to venture any farther, for which Dane didn’t blame them in the least. His toes just touched the sand; he sighed in relief. Exhausted, he exerted a last superhuman effort and thrust the women to safety. Fast regaining their senses, they began screaming again, thrashing about wildly. Gasping, Dane managed a grin. He had done his bit; the Poms could take over now. While he rested, chest heaving, the current had sucked him out again, his feet no longer brushed the bottom even when he stretched them downward. It had been a close call. If he hadn’t been present they would certainly have drowned; the Poms hadn’t the strength or skill to save them. But, said a voice, they only wanted to swim so they could be near you; until they saw you they hadn’t any intention of going in. It was your fault they were in danger, your fault.

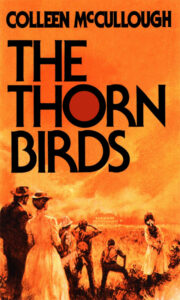

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.