They were almost to the last family present Catholic, and few sported Anglo-Saxon names; there was about an equal distribution of Irish, Scottish and Welsh. No, they could not hope for home rule in the old country, nor, if Catholic in Scotland or Wales, for much sympathy from the Protestant indigenes. But here in the thousands of square miles around Gillanbone they were lords to thumb their noses at British lords, masters of all they surveyed; Drogheda, the biggest property, was greater in area than several European principalities. Monegasque princelings, Liechtensteinian dukes, beware! Mary Carson was greater. So they whirled in waltzes to the sleek Sydney band and stood back indulgently to watch their children dance the Charleston, ate the lobster patties and the chilled raw oysters, drank the fifteen-year-old French champagne and the twelve-year-old single-malt Scotch. If the truth were known, they would rather have eaten roast leg of lamb or corned beef, and much preferred to drink cheap, very potent Bundaberg rum or Grafton bitter from the barrel. But it was nice to know the better things of life were theirs for the asking.

Yes, there were lean years, many of them. The wool checks were carefully hoarded in the good years to guard against the depredations of the bad, for no one could predict the rain. But it was a good period, had been for some time, and there was little to spend the money on in Gilly. Oh, once born to the black soil plains of the Great Northwest there was no place on earth like it. They made no nostalgic pilgrimages back to the old country; it had done nothing for them save discriminate against them for their religious convictions, where Australia was too Catholic a country to discriminate. And the Great Northwest was home.

Besides, Mary Carson was footing the bill tonight. She could well afford it. Rumor said she was able to buy and sell the King of England. She had money in steel, money in silver-lead-zinc, money in copper and gold, money in a hundred different things, mostly the sort of things that literally and metaphorically made money. Drogheda had long since ceased to be the main source of her income; it was no more than a profitable hobby.

Father Ralph didn’t speak directly to Meggie during dinner, nor did he afterward; throughout the evening he studiously ignored her. Hurt, her eyes sought him wherever he was in the reception room. Aware of it, he ached to stop by her chair and explain to her that it would not do her reputation (or his) any good if he paid her more attention than he did, say, Miss Carmichael, Miss Gordon or Miss O’Mara. Like Meggie he didn’t dance, and like Meggie there were many eyes on him; they were easily the two most beautiful people in the room.

Half of him hated her appearance tonight, the short hair, the lovely dress, the dainty ashes-of-roses silk slippers with their two-inch heels; she was growing taller, developing a very feminine figure. And half of him was busy being terrifically proud of the fact that she shone all the other young ladies down. Miss Carmichael had the patrician features, but lacked the special glory of that red-gold hair; Miss King had exquisite blond tresses, but lacked the lissome body; Miss Mackail was stunning of body, but in the face very like a horse eating an apple through a wire-netting fence. Yet his overall reaction was one of disappointment, and an anguished wish to turn back the calendar. He didn’t want Meggie to grow up, he wanted the little girl he could treat as his treasured babe. On Paddy’s face he glimpsed an expression which mirrored his own thoughts, and smiled faintly. What bliss it would be if just once in his life he could show his feelings! But habit, training and discretion were too ingrained.

As the evening wore on the dancing grew more and more uninhibited, the liquor changed from champagne and whiskey to rum and beer, and proceedings settled down to something more like a woolshed ball. By two in the morning only a total absence of station hands and working girls could distinguish it from the usual entertainments of the Gilly district, which were strictly democratic.

Paddy and Fee were still in attendance, but promptly at midnight Bob and Jack left with Meggie. Neither Fee nor Paddy noticed; they were enjoying themselves. If their children couldn’t dance, they could, and did; with each other mostly, seeming to the watching Father Ralph suddenly much more attuned to each other, perhaps because the times they had an opportunity to relax and enjoy each other were rare. He never remembered seeing them without at least one child somewhere around, and thought it must be hard on the parents of large families, never able to snatch moments alone save in the bedroom, where they might excusably have other things than conversation on their minds. Paddy was always cheerful and jolly, but Fee tonight almost literally shone, and when Paddy went to beg a duty dance of some squatter’s wife, she didn’t lack eager partners; there were many much younger women wilting on chairs around the room who were not so sought after.

However, Father Ralph’s moments to observe the Cleary parents were limited. Feeling ten years younger once he saw Meggie leave the room, he became a great deal more animated and flabbergasted the Misses Hopeton, Mackail, Gordon and O’Mara by dancing—and extremely well—the Black Bottom with Miss Carmichael. But after that he gave every unattached girl in the room her turn, even poor homely Miss Pugh, and since by this time everyone was thoroughly relaxed and oozing goodwill, no one condemned the priest one bit. In fact, his zeal and kindness were much admired and commented upon. No one could say their daughter had not had an opportunity to dance with Father de Bricassart. Of course, had it not been a private party he could not have made a move toward the dance floor, but it was so nice to see such a fine man really enjoy himself for once.

At three o’clock Mary Carson rose to her feet and yawned. “No, don’t stop the festivities! If I’m tired—which I am—I can go to bed, which is what I’m going to do. But there’s plenty of food and drink, the band has been engaged to play as long as someone wants to dance, and a little noise will only speed me into my dreams. Father, would you help me up the stairs, please?”

Once outside the reception room she did not turn to the majestic staircase, but guided the priest to her drawing room, leaning heavily on his arm. Its door had been locked; she waited while he used the key she handed him, then preceded him inside.

“It was a good party, Mary,” he said.

“My last.”

“Don’t say that, my dear.”

“Why not? I’m tired of living, Ralph, and I’m going to stop.” Her hard eyes mocked. “Do you doubt me? For over seventy years I’ve done precisely what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it, so if Death thinks he’s the one to choose the time of my going, he’s very much mistaken. I’ll die when I choose the time, and no suicide, either. It’s our will to live keeps us kicking, Ralph; it isn’t hard to stop if we really want to. I’m tired, and I want to stop. Very simple.”

He was tired, too; not of living, exactly, but of the endless façade, the climate, the lack of friends with common interests, himself. The room was only faintly lit by a tall kerosene lamp of priceless ruby glass, and it cast transparent crimson shadows on Mary Carson’s face, conjuring out of her intractable bones something more diabolical. His feet and back ached; it was a long time since he had danced so much, though he prided himself on keeping up with whatever was the latest fad. Thirty-five years of age, a country monsignor, and as a power in the Church? Finished before he had begun. Oh, the dreams of youth! And the carelessness of youth’s tongue, the hotness of youth’s temper. He had not been strong enough to meet the test. But he would never make that mistake again. Never, never…

He moved restlessly, sighed; what was the use? The chance would not come again. Time he faced that fact squarely, time he stopped hoping and dreaming.

“Do you remember my saying, Ralph, that I’d beat you, that I’d hoist you with your own petard?”

The dry old voice snapped him out of the reverie his weariness had induced. He looked across at Mary Carson and smiled.

“Dear Mary, I never forget anything you say. What I would have done without you these past seven years I don’t know. Your wit, your malice, your perception…”

“If I’d been younger I’d have got you in a different way, Ralph. You’ll never know how I’ve longed to throw thirty years of my life out the window. If the Devil had come to me and offered to buy my soul for the chance to be young again, I’d have sold it in a second, and not stupidly regretted the bargain like that old idiot Faust. But no Devil. I really can’t bring myself to believe in God or the Devil, you know. I’ve never seen a scrap of evidence to the effect they exist. Have you?”

“No. But belief doesn’t rest on proof of existence, Mary. It rests on faith, and faith is the touchstone of the Church. Without faith, there is nothing.”

“A very ephemeral tenet.”

“Perhaps. Faith’s born in a man or a woman, I think. For me it’s a constant struggle, I admit that, but I’ll never give up.”

“I would like to destroy you.”

His blue eyes laughed, greyed in the light. “Oh, my dear Mary! I know that.”

“But do you know why?”

A terrifying tenderness crept against him, almost inside him, except that he fought it fiercely. “I know why, Mary, and believe me, I’m sorry.”

“Besides your mother, how many women have loved you?”

“Did my mother love me, I wonder? She ended in hating me, anyway. Most women do. My name ought to have been Hippolytos.”

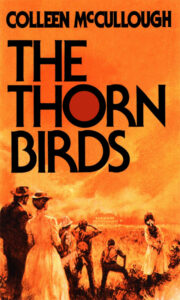

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.