Ignoring muffled sniggers from the lined-up children, Bob and his brothers stood perfectly still while the pupils marched inside to the sound of Sister Catherine plunking “Faith of Our Fathers” on the tinny school piano. Only when the last child had disappeared did Sister Agatha break her rigid pose; heavy serge skirts swishing the gravel aside imperiously, she strode to where the Clearys waited.

Meggie gaped at her, never having seen a nun before. The sight was truly extraordinary; three dabs of person, which were Sister Agatha’s face and hands, the rest white starched wimple and bib glaring against layers of blackest black, with a massive rope of wooden rosary beads dangling from an iron ring that joined the ends of a wide leather belt around Sister Agatha’s stout middle. Sister Agatha’s skin was permanently red, from too much cleanliness and the pressure of the knifelike edges of the wimple framing the front center of her head into something too disembodied to be called a face; little hairs sprouted in tufts all over her chin, which the wimple ruthlessly squashed double. Her lips were quite invisible, compressed into a single line of concentration on the hard business of being the Bride of Christ in a colonial backwater with topsy-turvy seasons when she had taken her vows in the sweet softness of a Killarney abbey over fifty years before. Two small crimson marks were etched into the sides of her nose from the remorseless grip of her round, steel-framed spectacles, and behind them her eyes peered out suspiciously, pale-blue and bitter.

“Well, Robert Cleary, why are you late?” Sister Agatha barked in her dry, once Irish voice.

“I’m sorry, Sister,” Bob replied woodenly, his blue-green eyes still riveted on the tip of the quivering cane as it waved back and forth.

“Why are you late?” she repeated.

“I’m sorry, Sister.”

“This is the first morning of the new school year, Robert Cleary, and I would have thought that on this morning if not on others you might have made an effort to be on time.”

Meggie shivered, but plucked up her courage. “Oh, please, Sister, it was my fault!” she squeaked.

The pale-blue eyes deviated from Bob and seemed to go through and through Meggie’s very soul as she stood there gazing up in genuine innocence, not aware she was breaking the first rule of conduct in a deadly duel which went on between teachers and pupils ad infinitum: never volunteer information. Bob kicked her swiftly on the leg and Meggie looked at him sideways, bewildered.

“Why was it your fault?” the nun demanded in the coldest tones Meggie had ever heard.

“Well, I was sick all over the table and it went right through to my drawers, so Mum had to wash me and change my dress, and I made us all late,” Meggie explained artlessly.

Sister Agatha’s features remained expressionless, but her mouth tightened like an overwound spring, and the tip of the cane lowered itself an inch or two. “Who is this?” she snapped to Bob, as if the object of her inquiry were a new and particularly obnoxious species of insect.

“Please, Sister, she’s my sister Meghann.”

“Then in future you will make her understand that there are certain subjects we do not ever mention, Robert, if we are true ladies and gentlemen. On no account do we ever, ever mention by name any item of our underclothing, as children from a decent household would automatically know. Hold out your hands, all of you.”

“But, Sister, it was my fault!” Meggie wailed as she extended her hands palms up, for she had seen her brothers do it in pantomime at home a thousand times.

“Silence!” Sister Agatha hissed, turning on her. “It is a matter of complete indifference to me which one of you was responsible. You are all late, therefore you must all be punished. Six cuts.” She pronounced the sentence with monotonous relish.

Terrified, Meggie watched Bob’s steady hands, saw the long cane whistle down almost faster than her eyes could follow, and crack sharply against the center of his palms, where the flesh was soft and tender. A purple welt flared up immediately; the next cut came at the junction of fingers and palm, more sensitive still, and the final one across the tips of the fingers, where the brain has loaded the skin down with more sensation than anywhere else save the lips. Sister Agatha’s aim was perfect. Three more cuts followed on Bob’s other hand before she turned her attention to Jack, next in line. Bob’s face was pale but he made no outcry or movement, nor did his brothers as their turns came; even quiet and tender Stu.

As they followed the upward rise of the cane above her own hands Meggie’s eyes closed involuntarily, so she did not see the descent. But the pain was like a vast explosion, a scorching, searing invasion of her flesh right down to the bone; even as the ache spread tingling up her forearm the next cut came, and by the time it had reached her shoulder the final cut across her fingertips was screaming along the same path, all the way through to her heart. She fastened her teeth in her lower lip and bit down on it, too ashamed and too proud to cry, too angry and indignant at the injustice of it to dare open her eyes and look at Sister Agatha; the lesson was sinking in, even if the crux of it was not what Sister Agatha intended to teach.

It was lunchtime before the last of the pain died out of her hands. Meggie had passed the morning in a haze of fright and bewilderment, not understanding anything that was said or done. Pushed into a double desk in the back row of the youngest children’s classroom, she did not even notice who was sharing the desk until after a miserable lunch hour spent huddled behind Bob and Jack in a secluded corner of the playground. Only Bob’s stern command persuaded her to eat Fee’s gooseberry jam sandwiches. When the bell rang for afternoon classes and Meggie found a place on line, her eyes finally began to clear enough to take in what was going on around her. The disgrace of the caning rankled as sharply as ever, but she held her head high and affected not to notice the nudges and whispers of the little girls near her.

Sister Agatha was standing in front with her cane; Sister Declan prowled up and down behind the lines; Sister Catherine seated herself at the piano just inside the youngest children’s classroom door and began to play “Onward, Christian Soldiers” with a heavy emphasis on two-four time. It was, properly speaking, a Protestant hymn, but the war had rendered it interdenominational. The dear children marched to it just like wee soldiers, Sister Catherine thought proudly.

Of the three nuns, Sister Declan was a replica of Sister Agatha minus fifteen years of life, where Sister Catherine was still remotely human. She was only in her thirties, Irish of course, and the bloom of her ardor had not yet entirely faded; she still found joy in teaching, still saw Christ’s imperishable Image in the little faces turned up to hers so adoringly. But she taught the oldest children, whom Sister Agatha deemed beaten enough to behave in spite of a young and soft supervisor. Sister Agatha herself took the youngest children to form minds and hearts out of infantile clay, leaving those in the middle grades to Sister Declan.

Safely hidden in the last row of desks, Meggie dared to glance sideways at the little girl sitting next to her. A gap-toothed grin met her frightened gaze, huge black eyes staring roundly out of a dark, slightly shiny face. She fascinated Meggie, used to fairness and freckles, for even Frank with his dark eyes and hair had a fair white skin; so Meggie ended in thinking her deskmate the most beautiful creature she had ever seen.

“What’s your name?” the dark beauty muttered out of the side of her mouth, chewing on the end of her pencil and spitting the frayed bits into her empty ink-well hole.

“Meggie Cleary,” she whispered back.

“You there!” came a dry, harsh voice from the front of the classroom.

Meggie jumped, looking around in bewilderment. There was a hollow clatter as twenty children all put their pencils down together, a muted rustling as precious sheets of paper were shuffled to one side so elbows could be surreptitiously placed on desks. With a heart that seemed to crumple down toward her boots, Meggie realized everyone was staring at her. Sister Agatha was coming down the aisle rapidly; Meggie’s terror was so acute that had there only been somewhere to flee, she would have run for her life. But behind her was the partition shutting off the middle grade’s room, on either side desks crowded her in, and in front was Sister Agatha. Her eyes nearly filled her pinched little face as she stared up at the nun in suffocated fear, her hands clenching and unclenching on the desktop.

“You spoke, Meghann Cleary.”

“Yes, Sister.”

“And what did you say?”

“My name, Sister.”

“Your name!” Sister Agatha sneered, looking around at the other children as if they, too, surely must share her contempt. “Well, children, are we not honored? Another Cleary in our school, and she cannot wait to broadcast her name!” She turned back to Meggie. “Stand up when I address you, you ignorant little savage! And hold out your hands, please.”

Meggie scrambled out of her seat, her long curls swinging across her face and bouncing away. Gripping her hands together, she wrung them desperately, but Sister Agatha did not move, only waited, waited, waited… Then somehow Meggie managed to force her hands out, but as the cane descended she snatched them away, gasping in terror. Sister Agatha locked her fingers in the bunched hair on top of Meggie’s head and hauled her closer, bringing her face up to within inches of those dreadful spectacles.

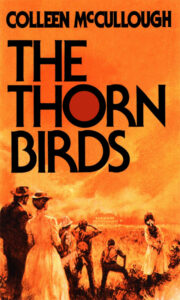

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.