The school year was drawing to a close, December and her birthday just beginning to threaten full summer, when Meggie learned how dearly one could buy the desire of one’s heart. She was sitting on a high stool near the stove while Fee did her hair as usual for school; it was an intricate business. Meggie’s hair had a natural tendency to curl, which her mother considered to be a great piece of good luck. Girls with straight hair had a hard time of it when they grew up and tried to produce glorious wavy masses out of limp, thin strands. At night Meggie slept with her almost knee-length locks twisted painfully around bits of old white sheet torn into long strips, and each morning she had to clamber up on the stool while Fee undid the rags and brushed her curls in.

Fee used an old Mason Pearson hairbrush, taking one long, scraggly curl in her left hand and expertly brushing the hair around her index finger until the entire length of it was rolled into a shining thick sausage; then she carefully withdrew her finger from the center of the roll and shook it out into a long, enviably thick curl. This maneuver was repeated some twelve times, the front curls were then drawn together on Meggie’s crown with a freshly ironed white taffeta bow, and she was ready for the day. All the other little girls wore braids to school, saving curls for special occasions, but on this one point Fee was adamant; Meggie should have curls all the time, no matter how hard it was to spare the minutes each morning. Had Fee realized it, her charity was misguided, for her daughter’s hair was far and away the most beautiful in the entire school. To rub the fact in with daily curls earned Meggie much envy and loathing.

The process hurt, but Meggie was too used to it to notice, never remembering a time when it had not been done. Fee’s muscular arm yanked the brush ruthlessly through knots and tangles until Meggie’s eyes watered and she had to hang on to the stool with both hands to keep from falling off. It was the Monday of the last week at school, and her birthday was only two days away; she clung to the stool and dreamed about the willow pattern tea set, knowing it for a dream. There was one in the Wahine general store, and she knew enough of prices to realize that its cost put it far beyond her father’s slender means.

Suddenly Fee made a sound, so peculiar it jerked Meggie out of her musing and made the menfolk still seated at the breakfast table turn their heads curiously.

“Holy Jesus Christ!” said Fee.

Paddy jumped to his feet, his face stupefied; he had never heard Fee take the name of the Lord in vain before. She was standing with one of Meggie’s curls in her hand, the brush poised, her features twisted into an expression of horror and revulsion. Paddy and the boys crowded round; Meggie tried to see what was going on and earned a backhanded slap with the bristle side of the brush which made her eyes water.

“Look!” Fee whispered, holding the curl in a ray of sunlight so Paddy could see.

The hair was a mass of brilliant, glittering gold in the sun, and Paddy saw nothing at first. Then he became aware that a creature was marching down the back of Fee’s hand. He took a curl for himself, and in among the leaping lights of it he discerned more creatures, going about their business busily. Little white things were stuck in clumps all along the separate strands, and the creatures were energetically producing more clumps of little white things. Meggie’s hair was a hive of industry.

“She’s got lice!” Paddy said.

Bob, Jack, Hughie and Stu had a look, and like their father removed themselves to a safe distance; only Frank and Fee remained gazing at Meggie’s hair, mesmerized, while Meggie sat miserably hunched over, wondering what she had done. Paddy sat down in his Windsor chair heavily, staring into the fire and blinking hard.

“It’s that bloody Dago girl!” he said at last, and turned to glare at Fee. “Bloody bastards, filthy lot of flaming pigs!”

“Paddy!” Fee gasped, scandalized.

“I’m sorry for swearing, Mum, but when I think of that blasted Dago giving her lice to Meggie, I could go into Wahine this minute and tear the whole filthy greasy café down!” he exploded, pounding his fist on his knee fiercely.

“Mum, what is it?” Meggie finally managed to say.

“Look, you dirty little grub!” her mother answered, thrusting her hand down in front of Meggie’s eyes. “You have these things everywhere in your hair, from that Eyetie girl you’re so thick with! Now what am I going to do with you?”

Meggie gaped at the tiny thing roaming blindly round Fee’s bare skin in search of more hirsute territory, then she began to weep.

Without needing to be told, Frank got the copper going while Paddy paced up and down the kitchen roaring, his rage increasing every time he looked at Meggie. Finally he went to the row of hooks on the wall inside the back door, jammed his hat on his head and took the long horsewhip from its nail.

“I’m going into Wahine, Fee, and I’m going to tell that blasted Dago what he can do with his slimy fish and chips! Then I’m going to see Sister Agatha and tell her what I think of her, allowing lousy children in her school!”

“Paddy, be careful!” Fee pleaded. “What if it isn’t the Eyetie girl? Even if she has lice, it’s possible she might have got them from someone else along with Meggie.”

“Rot!” said Paddy scornfully. He pounded down the back steps, and a few minutes later they heard his roan’s hoofs beating down the road. Fee sighed, looking at Frank hopelessly.

“Well, I suppose we’ll be lucky if he doesn’t land in jail. Frank, you’d better bring the boys inside. No school today.”

One by one Fee went through her sons’ hair minutely, then checked Frank’s head and made him do the same for her. There was no evidence that anyone else had acquired poor Meggie’s malady, but Fee did not intend to take chances. When the water in the huge laundry copper was boiling, Frank got the dish tub down from its hanging and filled it half with hot water and half with cold. Then he went out to the shed and fetched in an unopened five-gallon can of kerosene, took a bar of lye soap from the laundry and started work on Bob. Each head was briefly damped in the tub, several cups of raw kerosene poured over it, and the whole draggled, greasy mess lathered with soap. The kerosene and lye burned; the boys howled and rubbed their eyes raw, scratching at their reddened, tingling scalps and threatening ghastly vengeance on all Dagos.

Fee went to her sewing basket and took out her big shears. She came back to Meggie, who had not dared to move from the stool though an hour and more had elapsed, and stood with the shears in her hand, staring at the beautiful fall of hair. Then she began to cut it—snip! snip!—untill all the long curls were huddled in glistening heaps on the floor and Meggie’s white skin was beginning to show in irregular patches all over her head. Doubt in her eyes, she turned then to Frank.

“Ought I to shave it?” she asked, tight-lipped.

Frank put out his hand, revolted. “Oh, Mum, no! Surely not! If she gets a good douse of kerosene it ought to be enough. Please don’t shave it!”

So Meggie was marched to the worktable and held over the tub while they poured cup after cup of kerosene over her head and scrubbed the corrosive soap through what was left of her hair. When they were finally satisfied, she was almost blind from screwing up her eyes against the bite of the caustic, and little rows of blisters had risen all over her face and scalp. Frank swept the fallen curls into a sheet of paper and thrust it into the copper fire, then took the broom and stood it in a panful of kerosene. He and Fee both washed their hair, gasping as the lye seared their skins, then Frank got out a bucket and scrubbed the kitchen floor with sheep-dip.

When the kitchen was as sterile as a hospital they went through to the bedrooms, stripped every sheet and blanket from every bed, and spent the rest of the day boiling, wringing and pegging out the family linen. The mattresses and pillows were draped over the back fence and sprayed with kerosene, the parlor rugs were beaten within an inch of their lives. All the boys were put to helping, only Meggie exempted because she was in absolute disgrace. She crawled away behind the barn and cried. Her head throbbed with pain from the scrubbing, the burns and the blisters; and she was so bitterly ashamed that she would not even look at Frank when he came to find her, nor could he persuade her to come inside.

In the end he had to drag her into the house by brute force, kicking and fighting, and she had pushed herself into a corner when Paddy came back from Wahine in the late afternoon. He took one look at Meggie’s shorn head and burst into tears, sitting rocking himself in the Windsor chair with his hands over his face, while the family stood shuffling their feet and wishing they were anywhere but where they were. Fee made a pot of tea and poured Paddy a cup as he began to recover.

“What happened in Wahine?” she asked. “You were gone an awful long time.”

“I took the horsewhip to that blasted Dago and threw him into the horse trough, for one thing. Then I noticed MacLeod standing outside his shop watching, so I told him what had happened. MacLeod mustered some of the chaps at the pub and we threw the whole lot of those Dagos into the horse trough, women too, and tipped a few gallons of sheep-dip into it. Then I went down to the school and saw Sister Agatha, and I tell you, she was fit to be tied that she hadn’t noticed anything. She hauled the Dago girl out of her desk to look in her hair, and sure enough, lice all over the place. So she sent the girl home and told her not to come back until her head was clean. I left her and Sister Declan and Sister Catherine looking through every head in the school, and there turned out to be a lot of lousy ones. Those three nuns were scratching themselves like mad when they thought no one was watching.” He grinned at the memory, then he saw Meggie’s head again and sobered. He stared at her grimly. “As for you, young lady, no more Dagos or anyone except your brothers. If they aren’t good enough for you, too bad. Bob, I’m telling you that Meggie’s to have nothing to do with anyone except you and the boys while she’s at school, do you hear?”

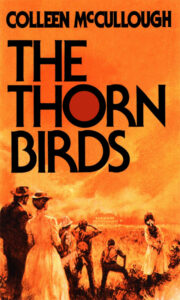

"The Thorn Birds" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Thorn Birds". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Thorn Birds" друзьям в соцсетях.