It was a great responsibility.

She guarded her health with the greatest care all during the cold dark autumn days, and early in January she went to St. James’s Palace to await the birth.

On the ninth of that month she knew her time was near; and with relief and apprehension waited for the beginning of her ordeal.

Outside the snow had begun to fall and the bitter wind blew along the river. Her women were bustling round her.

This was the most important birth in the kingdom.

She awoke on a dark Sunday knowing that her time had come; she called to her women.

It seemed to Mary Beatrice that all the world was waiting breathlessly for the child she would have.

She was aware of voices as she emerged from unconsciousness. The room was lighted by many candles and her pains were over.

Someone was bending over her.

“James,” she said.

“My dear.”

“The child?”

“The child is well and healthy. And you must rest now.”

“But I want to see …”

He said: “Bring the child.…”

The child? Why did he continue to say the child? She knew of course. Had it been a boy he would not have said the child.

They brought the little bundle; they laid it in her arms.

“Our little daughter,” said James tenderly.

“A daughter!”

But when she held the child in her arms she ceased to care that it was not a boy.

It was her child. She was a mother. She laughed scornfully at that foolish girl who had believed that the ultimate contentment could only be found within the walls of a convent.

She lay in her bed, drowsily content. My daughter, she thought. There would be others. Next time a son. But she was entirely content that this one should be a daughter.

She thought of the future of the child. Should she be brought up with her half-sisters? But they were much too old. Moreover they were in the care of the Protestant Bishop of London. The Protestant Bishop! Why should her child be brought up as a Protestant? She was a Catholic, James was a Catholic; even though he was not publicly known as one. Why should they not be allowed to bring up their children as they wished?

When James came to see her she told him that she wanted the child baptized as a Catholic.

“My dear,” said James, “that is not possible.”

“But why? I am a Catholic and so are you.”

“Our little daughter is in the line of succession to the throne. The people of England will not accept a Catholic baptism.”

“This is my daughter,” said Mary Beatrice obstinately.

“Alas, my dear, we are servants of the state.”

He did not discuss the matter further, but Mary Beatrice lying back on her pillows continued to brood. Why, because she was young, should she be continually told what she must do? She had been married against her will and nothing could alter that, even though she was now glad that she had been. She was not going to allow anyone to dictate to her where her child was concerned.

She sent for her confessor and when he came she said: “Father Gallis, I want you to make ready to baptize my daughter.”

Father Gallis raised his eyebrows, but she went on: “I want no interference. Indeed I will have no interference. My daughter shall be baptized in accordance with the rights of my Church. I care not what anyone says. That is what I have decided.”

Father Gallis, secretly pleased, obeyed his mistress and the little girl was christened on her mother’s bed, according to Rome.

Charles came to call on his sister-in-law.

He sat by the bed smiling at her.

“I have come to welcome my new subject,” he said genially.

The baby was brought to show him.

“She is charming,” he said, and he smiled from James, who had accompanied him, to the beautiful mother.

“You are very proud of your achievement,” he went on, “and rightly so. Have you decided on her names?”

“Yes, Your Majesty,” answered Mary Beatrice, “she is to be Catherine after Her Majesty.”

“A pretty compliment,” murmured Charles, “and one which will satisfy the Queen.”

“And Laura after my mother.”

“Who, rest assured, will be equally gratified. Now, let us talk about the arrangements for this blessed infant’s baptism.”

Mary Beatrice’s heart began to beat fast. It was one thing to talk defiance to her confessor; another to do so to the King’s face.

“Your Majesty,” she said slowly and she hoped firmly, “my daughter has already been baptized in accordance with my Church.”

Charles was silent for a few seconds then he smiled. “Catherine Laura,” he said. “What charming names!”

Mary Beatrice lay back on her pillows. She had won. She should have known that the easygoing King would let her have her own way.

The Queen came to visit her.

“I am so touched that the baby is to be named after me,” she said.

“I should perhaps have asked Your Majesty’s gracious permission.”

Catherine laughed. “It would have been readily given as you knew. And the King has asked me to discuss the baby’s baptism with you.”

“But …”

“It is His Majesty’s wish that it should take place in the chapel royal where the bishop will perform the ceremony.”

“In accordance with the Church of England?”

“But of course.”

“When did His Majesty request you to come to see me?”

“Only half an hour before I arrived.”

Mary Beatrice lay back on her pillows. He had shown no signs of anger. But then he rarely did. He had merely smiled and then made plans to have it done the way he wished it.

She was afraid then that some punishment would fall on Father Gallis for what he had done, and as soon as the Queen had left she sent for him and told him what had happened.

He said they could only wait for the King’s vengeance.

They waited. Nothing happened. And then the baby was baptized according to the King’s desire and the rites of the Church of England. Her sponsors were the Duke of Monmouth and the baby’s half-sisters, Anne and Mary.

The King did not refer to the matter again. He hated unpleasantness, Mary Beatrice was to learn; but at the same time he liked to have his way with as little fuss as possible.

Mary was in despair. The family of her dear Aurelia were moving from St. James’s Palace to St. James’s Square.

“What will this mean to us?” she demanded. “How can we meet when you are not at the Palace?”

“My dearest,” answered Aurelia, “we must content ourselves with letters when we are apart; my family will often be at St. James’s or Whitehall and you must contrive to be there when I am.”

Mary was a little comforted.

“I shall give you a cornelian ring so that when you look at it you will always remember me,” said Aurelia.

“It will comfort me,” answered Mary.

When she returned to Richmond she was pensive. Frances in St. James’s Square was no longer easily accessible but they would meet and there would be letters; it was a warning that life did not go on indefinitely in the same pleasant pattern.

Change came.

Daily she waited for Gibson to bring her the cornelian ring. Anne, who had wept with Mary when she had heard that Frances was moving from the Palace, declared that she too must have a ring for remembrance; and when the cornelian did not arrive Mary believed that Frances had sent it to Anne instead.

She poured out her jealous anguish in a letter.

“Not but that I think my sister do deserve your love more than I, but you have loved me once and now I do not doubt that my sister has the cornelian ring. Unkind Aurelia, I hope you will not go too soon, for I should be robbed of seeing you, unkind husband, as well as of your love, but she that has it will have your heart too and your letters, and oh, thrice happy she. She is happier than I ever was for she has triumphed over a rival that once was happy in your love, till she with her alluring charms removed unhappy Clorine from your heart …”

But Anne did not have the cornelian ring; and all in good time it came to Mary.

A happy day, which almost made her forget that communication would be more difficult now that Frances was going to St. James’s Square.

In spite of her love for Frances, which was all absorbing, Mary still had an affection for her cousin Monmouth; and now that she was growing up and was a great deal at Court she had many friends among the maids of honor. She was mildly fond of a number of them, but her passion for Frances meant that she had little room in her heart for others.

Eleanor Needham, a beautiful young girl, was a friend of both Mary and Frances; so that when Eleanor was in trouble and she had to confide in someone, she chose the Princess Mary.

But this did not happen until the interfering Sarah Jennings had made it necessary.

Sarah dominated whatever household she found herself in; her passion for management was irresistible to her. She had quarrelled with most of the maids of honor and was continually trying to call attention to herself. She had made the Princess Anne her special charge, but since Mary had become so attached to Frances (and Anne must follow her sister in everything) Anne had become less friendly with Sarah.

Sarah was alert; there was little she missed; and she it was who warned the Duchess of Monmouth to watch her husband and Eleanor Needham, for she was certain something was going on there.

The Duchess told Sarah to mind her own business, to which Sarah retorted that if she could not take a warning she was welcome to the consequences of her blindness. The Duchess accused her husband, mentioning Sarah, at which Monmouth called on Sarah and told her that if she did not keep her sharp nose out of his affairs she might not be in a position to much longer, for that same nose would not reach the Court from the place to which he would have her banished.

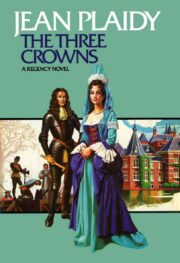

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.