“But he has no father, Mrs. Tanner,” said one of the women.

“Well, there’s no need to greet the baby with that knowledge. ’Tis something the little mite should come to know in time. And don’t call the child ‘he’ before you know the sex. That’s another bad omen.”

“The Princess is praying for a boy.”

“That’s tempting fate. Show as you’ll be pleased with what you get, and like as not you’ll get what you want.”

The women looked with respect at Mrs. Tanner, for she had attended so many births that they felt she knew what she was talking about.

“Then ’tis to be hoped the Princess gets what she wants—for if this little one’s a boy he’ll be the Stadtholder. They’ll call him William after his father and …”

“Hush I say. Hush. The air is full of omens tonight. I sense them.”

The women looked at each other in awe; and Mrs. Tanner left them. “For,” she said, “the child will be with us soon. I know it.”

She was right. Almost immediately the Princess’s pains had begun.

The welcome cry of a child! How often was that waited for in the palaces of kings? The words: “It is a boy.” How welcome and how rarely they came! It seemed that boys could be born in humble cottages but royal palaces were less favored. This was one of those occasions when wishes were granted.

William Henry, Prince of Orange, was born.

Mrs. Tanner, gossiping afterward to the women, assured them that it was no ordinary birth. Her little William—he was already hers—was destined for a great future. This day was one which was going to be remembered in the history of Orange.

“She was crying out in her anguish, our poor sad Princess; and I knew that the birth was near. Poor soul, she had forgotten the tragedy of her loss; there was nothing for her but the pain and the agony. And then … there he was … the blessed boy. And at that moment all the candles went out. So he came into a world of darkness. Poor blessed royal mite! He yelled; and I took him in my arms and shouted for light. I said: ‘This is a boy.’ And they all took up the cry and I had to remind them that I must have light. And then … while I was waiting for the lights to be brought … I saw it clearly. The darkness helped; and afterward I asked myself did the lights go out that I could see the symbol?”

“What symbol, Mrs. Tanner?”

Mrs. Tanner’s eyes were narrowed. “Three haloes of light … right about the baby’s head.”

“Does it mean he is going to be a monk and holy man, Mrs. Tanner?”

“Monk and holy man indeed! They were crowns. He’ll have three crowns, that blessed infant. I saw, I tell you.”

For a few days everyone talked about Mrs. Tanner’s vision. Then it was forgotten. After all, Mrs. Tanner was a romancer, several of them believed, for all that she posed as being such a wise woman. And of course this was an important little boy. He was the heir of Holland; more than that, the tragic death of his father made his birth the more joyous event. The Princess of Orange had a reason for living. The people of Holland had their new Stadtholder.

YOUNG WILLIAM

To young William the Palace in the Wood was home. This was a very beautiful house which his grandmother had had built within a mile or so of the state palace. Here he lived with Lady Stanhope, the governess chosen for him by his English mother—a serious little boy whom none were very sure of because he prided himself on keeping his opinions to himself. The fact that he was not strong was a great anxiety to his mother and those whose duty it was to care for him. William in his grave and serious way decided to make the utmost advantage of everything; therefore his weakness seemed an asset rather than a fact to be deplored. Because he was inclined to be asthmatical, his governess was in perpetual terror on his account. He was delicate and because his father was dead and there could be no other of the same line, he was very precious indeed.

William was aware of this, but in his cool judicial manner he knew exactly the reason why. He was small of stature and this hurt his pride; he could not compete with boys of his own age in sport; for one reason he had not the physique, for another his governors and governesses were always in fear of his overtaxing his strength.

“Oh,” he would say, “they will not allow me to do this or that.… It is because I have no father and am the Prince of Orange.”

That was well enough to say to others; but he accepted the true state of affairs. He had been born a Prince but of such weak body that he could not enjoy rough games. One could not have everything in life; therefore he would try to make up for physical imperfections by cultivating wisdom.

He was alert and missed little; he had heard an account of what Mrs. Tanner had seen at his birth. Three crowns! That sounded wonderful; when he stood beside tall strong boys he reminded himself of what Mrs. Tanner had seen at his birth. He would be ready to take the crowns when they came to him as he was sure they would. It would not matter then that he was not very tall and that he sometimes found breathing difficult.

He quickly learned that a country was not happy when its hereditary ruler was a minor. He was descended from great William the Silent who had won the gratitude of the Dutch because of what he had done for them in their struggle against Spain and the Inquisition, but his father was dead, he himself was a child, and de Witte with his Republicans was ruling Holland at this time. The office of Stadtholder had been abolished by the de Witte government soon after young William was born; and although he was the Prince of Orange and the son of rulers, while de Witte was supreme he could not be regarded as the future ruler.

His mother was a Princess of England; but alas, what help could be expected from a country which had executed its King and was now ruled by a commonwealth under a man such as Oliver Cromwell?

William was serious; William was determined; he realized at a very early age all that was expected of him, all that would be required of him. He had to win back the Stadtholder and make the House of Orange supreme again.

This he was certain he would do.

He was never driven to work at his lessons because it was feared that too much study might be bad for his health. He worked when he thought he would; and this was not infrequently. His mother’s maids of honor would often play games with him which were always sedate.

He would never forget the day when he was summoned to his mother’s apartments and told to expect an important visitor.

“Your cousin,” she told him, “is coming to stay with you for a while. I trust you will like her. She is Elizabeth Charlotte, and I want you to make her welcome.”

He expressed his willingness to do so, and wanted to hear more of this cousin.

“Her great-grandfather was James I of England and he was, as you know, also your great-grandfather, so you are cousins. She is a very gay little girl and I am sure you will enjoy her company. Sometimes, my dear boy, I think you are a little too serious.”

“Should I try to be more gay then, Mother?”

“Oh no, no, William. You must not over-excite yourself. But I think the company of Elizabeth Charlotte will be good for you.”

William was inclined to distrust that which was supposed to be good for him and was already thinking of his cousin with suspicion.

When she arrived, however, he could not help but be excited by her. She was a tomboy; she was pretty and she was determined on mischief.

“Of course,” she told him, when they were alone together, “you know why I am here?”

It was because they believed he should have a companion who would be “good” for him, he answered.

Elizabeth Charlotte laughed aloud and gave him a push which made him stagger. “They are planning to marry us. Depend upon it.”

“But they have said nothing to me.”

Elizabeth Charlotte put her hands on her hips. “And tell me, do you expect them to? No, we are children. We do as we’re told. And now they are putting us together that we may become accustomed to each other. Sooner or later it will be announced. The betrothal between William Prince of Orange, and his cousin Elizabeth Charlotte.”

“How can you know this?”

The little girl put her fingers to the tips of each ear, which she pulled out as far as it would go. “Oh,” she said lightly, “I use these. It’s what they’re meant for, Cousin William.”

William studied her intently, asking himself whether he wanted her for a wife. It would depend, of course, on what she had to bring him; but he supposed his mother would have thought of that.

“Have you seen my mother?” he asked.

She shook her head. “I am only a child, cousin. I am not presented to the Princess of Orange. I am in the care of my aunt Sophia who must do as she is told. She has brought me here to present me to the Princess of Orange.”

“Why must your aunt do as she is told?”

“William, how little you know! I can see I shall have a great deal to do if I am going to prepare you to be my husband. Aunt Sophia married for love—which it seems is a very silly thing to do. They have little money or position—her husband being one of the young princes of the House of Hanover. Poor Aunt Sophia! She is poor, and grandmamma, who is Queen of Bohemia, tells her what she must do. This is her latest duty to bring me here and to present me to the Princess of Orange.”

“And to see that you and I become good friends.”

“That is not important. Whether we are friends or not, they will marry us … unless you or I get a better offer before we reach the right age. But in case we do have to marry, we may as well get to like each other, do you not agree? After all, no harm will be done. We can always be good friends and then if I am somebody else’s Queen and you are Prince of Holland, we can help each other. Send men and arms to help fight our enemies. Do you not think that is an excellent idea, William?”

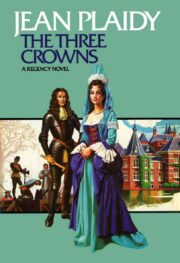

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.