She says nothing, leading the way past the closed doors. I am following her blindly, searching for words that will make her stop, turn, agree, as she opens the double doors of a darkened room.

“He is your ward,” I say. “He should be in your keeping.”

She does not answer me. “Here. Come in. Rest.”

I step inside. “Lady Margaret, I beg of you . . .” I start, and then I see that her ladies have followed us into the shadowy room and one of them has turned the key in the lock of the door and given it quietly to My Lady.

“What are you doing?” I demand.

“This is your confinement chamber,” she answers.

Now, for the first time, I realize where she has led me. It is a long, beautiful room with tall arched windows, blocked with tapestries so that no light creeps in. One of the ladies-in-waiting is lighting the candles, their yellow flickering light illuminating the bare stone walls and the high arched ceiling. The far end of the room is sheltered by a screen, and I can see an altar and the candles burning before a monstrance, a crucifix, a picture of Our Lady. Before the screen are prayer stools and before them the fireplace and a grand chair and lesser stools arranged in a conversational circle. Chillingly, I see that my sewing is on the table by the grand chair, and the book that I was reading before I lay down for my nap has been taken from my bedchamber and is open beside it.

Next is a dining table and six chairs, wine and water in beautiful Venetian glass jugs on the table, gold plates ready for serving dinner, a box with pastries in case of hunger.

Nearest to us is a grand bed, with thick oak posts and rich curtains and tester. On an impulse I open the chest at the foot of the bed and there, neatly folded and interspersed with dried lavender flowers, are my favorite gowns and my best linen, ready for me to wear when they fit me again. There is a day bed, next to the chest, and a beautifully carved and engraved royal cradle, all ready with linen beside the bed.

“What is this?” I ask as if I don’t know. “What is this? What is this?”

“You are in confinement,” Lady Margaret says patiently, as if speaking to an idiot. “For your health and for the health of your child.”

“What about Teddy?”

“He has been taken to the Tower for his own safety. He was in danger here. He needs to be carefully guarded. But I will speak to the king about your cousin. I will tell you what he says. Without question, he will judge rightly.”

“I want to see the king now!”

She pauses. “Now, daughter, you know that you cannot see him, or any man, until you come out of confinement,” she says reasonably. “But I will give him any message or take him any letter you wish to write.”

“When I have given birth you will have to let me out,” I say breathlessly. It is as if the room is airless and I am struggling to breathe. “Then I will see the king and tell him that I have been imprisoned in here.”

She sighs as if I am very foolish. “Really, Your Grace! You must be calm. We all agreed you were entering your confinement this evening, you knew full well that you were doing this today.”

“What about the dinner and bidding farewell to the court?”

“Your health was not strong enough. You said so yourself.”

I am so amazed by her lie that I gape at her. “When did I say that?”

“You said you were distressed. You said you were troubled. Here there is neither distress nor trouble. You will stay here, under my guidance, until you have safely given birth to the child.”

“I will see my mother, I will see her at once!” I say. I am furious to hear my voice tremble. But I am afraid of My Lady in this darkened room, and I feel powerless. My earliest memory is of being confined, in sanctuary, in a damp warren of cold rooms under the chapel at Westminster Abbey. I have a horror of confined spaces and dark places, and now I am trembling with anger and fear. “I will see my mother. The king said that I should see her. The king promised me that she would be with me in here.”

“She will come into confinement with you,” she concedes. “Of course.” She pauses. “And she will stay with you until you come out. When the baby is born. She will share your confinement.”

I just gape at her. She has all the power and I have none. I have been as good as imprisoned by her and by the convention of royal births which she has codified and to which I agreed. Now I am locked in one shadowy room for weeks, and she has the key.

“I am free,” I say boldly. “I’m not a prisoner. I am here to give birth. I chose to come in here. I am not held against my will. I am free. If I want to walk out, I can just walk out. Nobody can stop me, I am the wife of the King of England.”

“Of course you are,” she says, and then she goes out through the door and turns the key in the lock from the outside, and leaves me. I am locked in.

My mother comes in at dinnertime, holding Maggie’s hand. “We’ve come to join you,” she says.

Maggie is white as if she were deathly sick, her eyes red-rimmed from crying.

“What about Teddy?”

My mother shakes her head. “They took him to the Tower.”

“Why would they do that?”

“They shouted À Warwick when they fought Jasper Tudor in the North. They carried the standard of the ragged staff in London,” my mother says, as if this is reason enough.

“They were fighting for Teddy,” Maggie tells me. “Even though he didn’t ask them to—even though he would never ask them to. He knows not to say such things. I’ve taught him. He knows that King Henry is the king. He knows to say nothing about the House of York.”

“There’s no charge against him,” my mother says briefly. “He’s not charged with treason. Not charged with anything. The king says he is only acting to protect Teddy. He says that Teddy might be seized by rebels and used by them as a figurehead. He says that Teddy is safer in the Tower for now.”

My laughter at this extraordinary lie turns into a sob. “Safer in the Tower! Were my brothers safer in the Tower?”

My mother grimaces.

“I’m sorry,” I say at once. “Forgive me, I’m sorry. Did the king say how long he will keep Teddy there?”

Maggie goes quietly to the fireside and sinks down onto a footstool, her head turned away. “Poor child,” my mother says. To me she replies, “He didn’t say. I didn’t ask. They took Teddy’s clothes and his books. I think we have to assume that His Grace will keep him there until he feels safe from rebellion.”

I look at her, the only one of us who may know how many rebels are biding their time, waiting for a call to rise for York, seeing the last skirmish as a stepping-stone to another, and from that to another—not as a defeat. She is a woman who never sees defeat. I wonder if she is their leader, if it is her determined optimism that drives them on. “Is something going to happen?”

She shakes her head. “I don’t know.”

PRIOR’S GREAT HALL, WINCHESTER, 19 SEPTEMBER 1486

When my father came home, won two battles one after the other, saved us, rescued us like a knight in a storybook, we emerged from the crypt, out of the darkness like the risen Lord Himself coming into light. Then I swore to myself a childish oath that I would never be confined again.

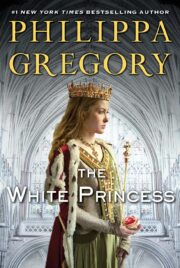

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.