I stand beside Henry, both in our best robes as we watch the long procession, each guild headed by a gorgeously embroidered banner and a litter carrying a display to celebrate their work or show their patron saint. Now and then I can see Henry glance sideways at me. He is watching me as the guilds go by. “You smile at someone when he catches your eye,” he says suddenly.

I am surprised. “Just out of courtesy,” I say defensively. “It means nothing.”

“No, I know. It’s just that you look at them as if you wish them well; you smile in a friendly way.”

I cannot understand what he is saying. “Yes, of course, my lord. I’m enjoying the procession.”

“Enjoying it?” he queries as if this explains everything. “You like this?”

I nod, though he makes me feel almost guilty to have a moment of pleasure. “Who would not? It’s so rich and varied, and the tableaux so well made, and the singing! I don’t think I’ve ever heard such music.”

He shakes his head in impatience at himself, and then remembers everyone is watching us and raises a hand to a passing litter with a splendid castle built out of gold-painted wood. “I can’t just enjoy it,” he says. “I keep thinking that these people put on this show, but what are they thinking in their hearts? They might smile and wave at us and doff their hats, but do they truly accept my rule?”

A little child, dressed as a cherub, waves at me from a pillow of white on blue, representing a cloud. I smile and blow him a kiss, which makes him wriggle with delight.

“But you just enjoy it,” Henry says, as if pleasure was a puzzle to him.

I laugh. “Ah well,” I say. “I was raised in a happy court and my father loved nothing better than a joust or a play or a celebration. We were always making music and dancing. I can’t help but enjoy a spectacle, and this is as fine as anything I have ever seen.”

“You forget your worries?” he asks me.

I consider. “For a moment I do. D’you think that makes me very foolish?”

Ruefully, he smiles. “No. I think you were born and raised to be a merry woman. It is a pity that so much sorrow has come into your life.”

There is a roar of cannon, in salute from the castle, and I see Henry flinch at the noise, and then grit his teeth and master himself.

“Are you well, my lord husband?” I ask him quietly. “Clearly you’re not easily amused like me.”

The face he turns to me is pale. “Troubled,” he says shortly, and I remember with a sudden pulse of dread that my mother said that the court was at Norwich because Henry expects an invasion on the east coast, and that I have been smiling and waving like a fool while my husband fears for his life.

We follow the procession into the great cathedral for the solemn mass of Corpus Christi, where My Lady the King’s Mother drops to her knees the moment that we enter, and spends the entire two-hour service bent low. Her more devout ladies-in-waiting kneel behind her, as if they were all part of an order of exceptional devotion. I think of my mother naming My Lady as Madonna Margaret of the Unending Self-Congratulation, and have to compose my face into a serious expression as I sit beside my husband on a pair of great matching chairs and listen to the long service in Latin and watch the service of the Mass.

Today, as it is such an important feast day, we will take communion and Henry and I go side by side up to the altar, my ladies following me, his court following him. At the moment that he is offered the sacred bread I see him hesitate, for one revealing second, before he opens his mouth and takes it, and I realize this is the only time that he does not have a taster to make sure his food is not poisoned. The thought that he might close his lips to the Host, to the sacred bread of the Mass, the body of Christ Himself, makes me shut my eyes in horror. When it is my turn, the wafer is dry in my mouth at that thought. How can Henry be so afraid that he thinks he is in danger before the altar of a cathedral?

The chancel rail is cold beneath my forehead as I kneel to pray and I remember that the church is no longer a place of holy safety. Henry has pulled his enemies out of sanctuary and put them to death; why should he not be poisoned at the altar?

I walk back to my throne, past My Lady the King’s Mother, who is still on her knees, and know that her anguished expression is because she is praying earnestly for her son’s safety in this country that he has won, but cannot trust.

When the service is over we go to a great banquet in the castle, and there are mummers and dancers, a pageant and a choir. Henry sits on his great chair at the head of the hall and smiles, and eats well. But I see his brown gaze raking the room, and the way that his hand is always clenched on the arm of his chair.

We stay on in Norwich after Corpus Christi and the court makes merry in the sunny weather; but I soon realize that Henry is planning something. He has men at every port along the coast appointed to warn him of foreign shipping. He organizes a series of beacons that are to be lit if a fleet is sighted. Every morning he has men brought into his room by a private covered way directly leading from the stable yard to the big plain room he has taken for his councils. Nobody knows who they are, but we all see sweat-stained horses in the stables, and men who will not stop to dine in the great hall, who have no time for singing or drinking but say that they will get their meat on the road. When the stable lads ask them, “Which road?” they won’t say.

Suddenly, Henry announces that he is going on a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, a full day’s ride north. He will go without me to this holy shrine.

“Is there something wrong?” I ask him. “Don’t you want me to come with you?”

“No,” he says shortly. “I’ll go alone.”

Our Lady of Walsingham is famous for helping barren women. I cannot think why Henry would suddenly want to make a pilgrimage there.

“Will you take your mother? I can’t understand why you would want to go.”

“Why shouldn’t I go to a holy shrine?” he asks irritably. “I’m always observing saints’ days. We’re a devout family.”

“I know, I know,” I placate him. “I just thought it was odd. Will you go quite alone?”

“I’ll take only a few men. I’ll ride with the Duke of Suffolk.”

The duke is my uncle, married to my father’s sister Elizabeth, and the father of my missing cousin John de la Pole. This only makes me more uneasy.

“As a companion? You choose the Duke of Suffolk as your principal companion to go on pilgrimage?”

Henry shows me a wolfish smile. “What else but as my companion? He has always been so faithful and loyal to me. Why would I not want to ride with him?”

I have no answer to this question. Henry’s expression is sly.

“Is it to speak to him about his son?” I venture. “Are you going to question him?” I cannot help but be anxious for my uncle. He is a quiet, steady man who fought for Richard at Bosworth but sought and obtained a pardon from Henry. His father was a famous Lancastrian, but he has always been devoted to the House of York, married to a York duchess. “I am certain, I am absolutely certain that he knows nothing about his son John’s running away.”

“And what does John de la Pole’s mother know? And what does your mother know?” Henry demands.

When I am silent he laughs shortly. “You are right to be anxious. I feel that I can trust none of the York cousins. Do you think I am taking your uncle as a hostage for the good behavior of his son? D’you think I’m going to take him away from everyone and remind him that he has another son and that the whole family might easily go on from Walsingham to the Tower? And from there to the block?”

I look at my husband and fear this icy fury of his. “Don’t speak of the Tower and the block,” I say quietly. “Please don’t speak of such things to me.”

“Don’t give me cause.”

ST. MARY’S IN THE FIELDS, NORWICH, SUMMER 1487

Then, one evening, Henry comes to my room, not dressed for bed but in his day clothes, his lean face compressed and dark. “The Irish have run mad,” he says shortly.

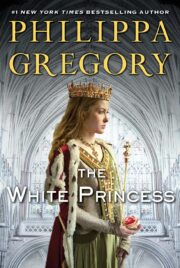

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.