He shakes his head. “No, because they weren’t all beside me at Stoke. Some of them found an excuse to stay away. Some of them said they would come but delayed and were not there in time. Some of them promised their love and loyalty but flatly refused to come. Some of them pretended to illness, or could not leave their homes. Some were even there, but on the other side, and begged for my forgiveness afterwards. And anyway, even of those who were there—they won’t stand by me again, not again and again. They won’t stand by me against a boy under the white rose, not one who they believe is a true prince.”

He goes back to the table where his letters and his secret ciphers and his seals are carefully laid out. He never writes a letter now, he always composes code. He hardly ever writes so much as a note, it is always a secret instruction. It is not the writing table of a king but of a spymaster. “I won’t detain you,” he says shortly. “But if someone says so much as one word to you—I expect you to tell me. I want to hear anything, everything—the slightest whisper. I expect this of you.”

I am about to say of course I would tell him, what else does he think I would do? I am his wife, his heirs are my beloved sons, there are no beings in the world that I love more tenderly than his own daughters—how can he doubt that I would come to him at once? But then I see his dark scowl and I realize that he is not asking for my help; he is threatening me. He is not asking for reassurance but warning me of his expectation that must not be disappointed. He does not trust me, and, worse than that, he wants me to know that he does not trust me.

“I am your wife,” I say quietly. “I promised to love you on our wedding day and since then I have come to love you. Once we were glad that such love had come to us; I am still glad of it. I am your wife and I love you, Henry.”

“But before that, you were his sister,” he says.

KENILWORTH CASTLE, WARWICKSHIRE, SUMMER 1493

Jasper Tudor, grim-faced, rides out to the West Country and Wales to uncover the dozens of local conspiracies that are joining together to welcome an invasion. None of the people of the west is for Tudor, they are all looking for the prince over the water. Henry himself opens other inquiries, riding from one place to another, chasing whispers, trying to find those who are behind the constant flow of men and funds to Flanders. Everywhere from Yorkshire to Oxfordshire, from the east to the central counties, Henry’s appointed men hold inquiries trying to root out rebels. And still the reports of treasonous groups, hidden meetings, and musters after dark come in every day.

Henry closes the ports. No one shall set sail to any destination for fear that they are going to join the boy; even merchants have to apply for a license before they can send out their ships. Not even trade is trusted. Then Henry passes another law: no one is to travel any great distance inland either. People may go to their market towns and back home again, but there is to be no mustering and marching. There are to be no summer gatherings, no haymaking parties, no shearing days, no dancing or beating of the parish bounds, no midsummer revels. The people are not to come together for fear that they make a crowd and raise an army, they are not to raise a glass for fear that they drink a toast to the prince whose family’s court was a byword for merrymaking.

My Lady the King’s Mother is bleached with fear. When she whispers the prayers of the rosary her lips are as pale as the starched wimple around her face. She spends all her time with me, leaving the best rooms, the queen’s apartments, empty all day. She brings her ladies and the members of her immediate family as the only people that she can trust, and she brings her books and her studies, and she sits in my rooms as if she is seeking warmth or comfort or some sort of safety.

I can offer her nothing. Cecily, Anne, and I barely speak to one another, we are so conscious that everything we say is being noted, that everyone is wondering if our brother will come to rescue us from this Tudor court. Maggie, my cousin, goes everywhere with her head down and her eyes on her feet, desperate that no one will say if one York boy is on the loose, then at least the other one could be put to death and so secure the Tudor line from his threat. The guards on Teddy have been doubled and doubled again, and Maggie is sure that he does not get his letters from her. She never hears from him and now she is too afraid to ask after him. We all fear that one day they will get the order to go into his room while he is asleep and strangle him in his bed. Who would countermand the order? Who would stop them?

The ladies in my rooms read and sew, play music and games, but everything is muted and nobody speaks quickly or laughs or makes a joke. Everyone examines everything they say before they let one word out of their mouths. Everyone is watching their own words for fear of saying something that could be reported against them, everyone is listening to everyone else, in case there is something that they should report. Everyone is silently attentive to me, and whenever there is a loud knock at my door, there is an indrawn breath of terror.

I hide from these terrible afternoons in the children’s nursery, taking Elizabeth onto my lap and stretching out her little hands and feet, singing softly to her, trying to persuade her to show me her faint, enchanting smile.

Arthur, who has to stay with us until we can be certain of the safety of Wales, is torn between his studies and the view from the high window, where he can see his father’s army growing in numbers, drilling every day. Every day too he sees messengers coming from the west, bringing news from Ireland or from Wales, or from the south—from London, where the streets are buzzing with gossip and the apprentices are openly wearing white roses.

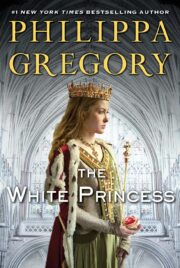

"The White Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.