It was only faintly alarming; Helen had just sent word to say that Leopold had slipped and damaged his knee. A trifling matter with most people, but the slightest injury in Leopold’s case could bring on the dreaded bleeding.

The Queen felt depressed. She wondered whether she should go out to Cannes. Helen understood the care that had to be taken and so did Leopold’s servants; but Helen was expecting her second child. The Queen was uncertain what to do. Mr Gladstone was always so peevish when she suggested leaving the country. Oh, how she missed the kind understanding of Lord Beaconsfield!

And the next day came the terrible news. Leopold was dead. He had had a kind of epileptic fit which had been brought on by a haemorrhage of the brain.

So she had lost another child.

‘He was the dearest of my sons,’ she said; but she knew that this was what they had been forced to expect ever since they had discovered his weakness. She should be thankful that he had been spared to her for so long.

His body was brought home and he was buried in St George’s Chapel at Windsor.

Three months later his posthumous son was born.

An anxious time followed Leopold’s death and the Queen’s mind was taken from family concerns to State matters.

She was very dissatisfied with her government; there was anxiety about Egypt, the affairs of which country were now almost completely under British domination. A fanatical leader known as the Mahdi had arisen in the Sudan which was under Egyptian rule and therefore a concern of Britain. The government, to the Queen’s dismay, decided that it would be better to abandon the Sudan and leave it in the control of the Mahdi, agreeing however to rescue the Egyptian forces which still remained there. Their efforts to do this were so dilatory that there was, as the Queen described it, unnecessary massacre; but finally the government agreed to send out General Gordon to Khartoum.

Mr Gladstone’s conception of Empire was, alas, not that of Lord Beaconsfield; and the Queen considered it the height of disaster to the country that that clever, far-sighted man had died to leave matters in the hands of The People’s William.

There was also much with which to concern herself at home. Bertie had been elected as a member of the Royal Commission on the Housing of the Working Classes. Mr Gladstone was constantly deploring the fact that Bertie had too little with which to occupy himself and to give Bertie his due he did enjoy having some task presented to him; it might well have been that had he been given some post he would not have got into such mischief as he did.

Bertie had become far too friendly with Sir Charles Dilke, that dreadful radical, and now the Prince himself was becoming something of a radical.

He was taken round London to see how the poor lived and declared himself to be horrified. First of all a typical working man’s dress had to be found for him and he went incognito in company with others. He came back to her – and told her what he had seen.

Poor Bertie, with all his faults he was very kind-hearted; there were tears in his eyes as he kept reiterating: ‘Something must be done.’

‘There was a room without any furniture, Mama,’ he went on. ‘A heap of rags and a poor skeleton of a woman lying on it, too weak to move; her children had no clothes whatsoever … I wanted to empty my pockets of everything I had but I was told that if I showed so much … so much, Mama, there would be a riot. These people would not believe there was so much money in the world! Something must be done.’

She herself agreed to this. Something must be done. General Booth and his Salvation Army were making people aware of conditions in the poor districts like those of St Giles’.

She read The Bitter Cry of Outcast London and wept.

She discussed it with the Prime Minister and she wondered why men who were so concerned with religion and the vote seemed to think that the distressing housing conditions and starvation of the poor was of less moment. She even felt a little drawn towards Sir Charles Dilke.

‘I begin now,’ she said, ‘to understand his concern for poor people.’

There was worse to follow. General Gordon had reached Khartoum where he was besieged by the Mahdi and his men.

‘He must be relieved at once,’ insisted the Queen.

Mr Gladstone’s Ministry was as usual dilatory; his government, he said, had no desire to be involved in a war in Egypt.

The people were with the Queen and they deplored the government’s neglect of those men fighting the Empire’s battles far away. Then before the relief arrived General Gordon was killed at the storming of Khartoum; she was furious with her government and at the same time very sad. She could not honour his family enough and fell back to her usual method of showing respect by having a bust made and placing it in Windsor Castle.

But in spite of the fact that relieving forces eventually arrived the Sudanese expedition was far from an unqualified success and she brooded on the fact that had Lord Beaconsfield been in command it would have been very different.

Of all her children the Queen had perhaps relied most on Beatrice since Albert’s death. Beatrice had then been ‘Baby’ and her quaint doings and sayings had diverted the Queen in her misery. As the youngest, Beatrice – still sometimes known as Baby – had been more constantly with her mother than any of the others. She was now the only one left; she was twenty-seven and the Queen had told herself that Beatrice would never marry. For one thing she was very shy; she disliked going to dinner-parties unless she was certain who her neighbours at the table would be and they were old friends. So naturally the Queen had imagined that she would always have Beatrice with her.

Her dismay was great when Beatrice came to her and said: ‘Mama, I have fallen in love and want to get married.’

The Queen almost fell off her chair. ‘In love!’ she said. ‘What nonsense, dearest child. How could you fall in love?’

‘It was not very difficult, Mama, and I am sure you will agree with me, when you know it is Henry.’

‘Henry. What Henry is this?’

‘Prince Henry of Battenberg.’

‘It’s quite impossible.’

‘Oh no, Mama, quite possible … if you give your consent.’

‘I should never allow you to be so foolish. My dearest child, you were so desolate when darling Leopold died. And this … Henry came along and you imagined you wished to marry him. Everything will settle down in time. Don’t worry.’

Poor Beatrice! Gone were the days of childhood when her quaintness had made it permissible to disagree with Mama.

She grew pale, wan and listless. She was obedient, but her conversation was dull and confined to ‘Yes, Mama’ and ‘No, Mama’ which was quite boring.

‘What is the matter with you, child?’ demanded the Queen. ‘And don’t talk to me about this foolish matter of Henry of Battenberg.’

‘Then there is nothing to be said, Mama,’ replied Beatrice.

Of course the Queen could not stand by and see poor Baby growing pale and thin. She supposed she would have to give way.

At length she said, ‘I had better see this Henry of Battenberg.’

He came; he was charming; he was devoted to Beatrice and to see the change in that dear child made the Queen weep.

Henry said he did understand her reluctance to part with such a treasure and they would reside in England so that their marriage would make little difference to the Queen.

She embraced them both and wished them well; and referred to herself in a letter to Vicky as ‘Poor shattered me.’

Of course it was not a grand marriage and Vicky would not approve of that; but the Queen wondered whether Vicky’s, which had been grand, had brought her much happiness. Beatrice was radiant; and the Queen reproached herself for ever trying to keep such joy from her dearest child.

She embraced her warmly but when Prince Henry and his new wife left for their honeymoon she shivered a little. She hoped poor Beatrice would not suffer too much from the ‘shadow side’ of marriage.

A great scandal had broken on London. A Mr Donald Crawford M.P. was suing for divorce and whom should he name as co-respondent but Sir Charles Dilke.

The Queen was very interested when she heard. ‘Oh, these radicals!’ she said to Beatrice. ‘They are so concerned for the rights of this and that, so anxious to look into the purses of other people, when all the time they themselves are not beyond reproach.’

But almost immediately she was anxious on account of Bertie. He did seem to have a habit of being mixed up in public scandals. She would never forget that dreadful Mordaunt case; and then there was that horrible Aylesford affair. And he was a friend of Sir Charles Dilke.

Happily Bertie was not involved in this one; and it was a great relief that he was not for it was the most shocking of them all.

The Dilke case was the great cause célèbre of the 1880s. It seemed that everyone from the Queen to her humblest subject was following the details as they emerged. The situation was one which could not fail to appeal. The dignified celebrated politician caught up in a very sordid affair and shown in the worst possible light. It appeared that Mr Crawford had received an anonymous letter advising him to ‘Beware of the Member for Chelsea!’ – the Member for Chelsea being Sir Charles Dilke. He had been inclined to think that this was the work of a practical joker until he received a second unsigned letter:

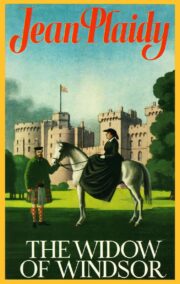

"The Widow of Windsor" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Widow of Windsor". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Widow of Windsor" друзьям в соцсетях.