But soon I began to tune out the noises and cuddle up in my blankets so much that I felt somewhat cocooned by them. Eventually, exhaustion took over and I started to drift off.

Before I could get into a deep sleep, though, I was awakened by the crunching of gravel under car tires. I didn’t even fully realize that was what I was hearing until the slams of two car doors split the air.

I sat up on the couch, hearing footsteps coming around the house, hushed voices floating over the sudden silence.

The screen door slammed open, knocking my heart practically out of my chest, and then there was a scent of alcohol, and a booming voice. “Well, I’ll be a sonofabitch,” it said.

I blinked and peered through the darkness, into narrow, brown eyes that matched mine.

Standing in the doorway, swaying crookedly, balanced on a pair of beat-up cowboy boots, was my father, Clay Cameron.

CHAPTER

FIFTEEN

A short woman stood behind Clay, her hands on his back as if to hold him up, a gut hanging over the top of her too-tight jeans.

“Oh, goody,” she slurred, sounding as drunk as he looked. “The sperm donation is here.” She giggled.

“Shut up, Tonette,” he said, his words soggy. He leaned over further, his hands clutching the doorframe tight for balance. He peered at me, his head bobbing up and down and side to side, making me feel seasick. I could smell his breath all the way across the porch. “You Jersey?” he said.

I nodded, even though I wasn’t sure if he could see me. “Yes.”

“Your mom really did die, then, huh?”

“Yes, sir. My sister, Marin, too.”

“I ain’t got no daughter Marin,” he said confusedly, and the woman smacked him between the shoulder blades. “Your mother lies.”

“You better fuckin’ not,” the woman said.

“She was my half sister.”

“ ’S real shame,” he said, then stumbled across the porch, his boots so loud on the boards I wondered how his footsteps weren’t waking everyone in the neighborhood. He disappeared into the house. “Real damn shame.”

The woman staggered after him, swallowed up in the darkness of the kitchen, her whisper escaping before the screen door could swing all the way shut.

“… always said you wanted the bitch dead,” she said, and I heard them both giggle. I sat for a while and stared out into the dark yard, the noises outside no longer even registering with me. I’d seen my father for the first time that I could remember in my entire life, and he’d been drunk. Of course. He hadn’t even asked if I was okay or said he was sorry I’d lost everything. He hadn’t asked one thing about the tornado, and neither had anyone else in the house. Nobody even seemed to care about it. It had devastated our town, killed our families, and they watched their TV shows and drank their booze like it was any other day.

I considered the nasty woman Tonette, talking about my mom without even knowing her. Coming in drunk on a weeknight. Giggling about someone being dead. Her shirt cut low so that her cleavage, even in the dark, was startling. She couldn’t have been any more different from my mom if she’d tried. What could Clay possibly have seen in that woman that he didn’t see in my mom?

I was wide awake. Sleep wasn’t going to come easily, not for me, not now. I got up and walked around to the back of the couch, digging out Marin’s purse. I grabbed a stick of gum, emptying the first pack, a little startled by how quickly it had gone.

I opened up the foil, feeling guilty that I’d called her my half sister to my dad and Tonette. Mom had never allowed us to call each other anything but sisters.

“She’s got a different daddy, but she’s your sister. No half about it,” Mom had told me when Marin was first born, a red, wrinkly squiggle of a thing wrapped up and grunting in a yellow ducky blanket.

“But Dani said that Marin’s not my real sister if we’ve got two different daddies. She said that’s what makes her a half sister.”

Mom’s face had darkened, a frown crinkling her brow as she bounced Marin up and down lightly in her lap. “You tell Dani what makes someone a sister isn’t what’s in your blood. It’s what’s in your heart.”

Since then, I’d never called Marin a half sister, not to her face. I wasn’t even sure if Marin was fully aware that we had two different fathers, though she did sometimes wonder aloud why I didn’t call Ronnie “Daddy” like she did.

I sketched an oval-shaped blanket bundle with a little round head at the top of it. Marin is my sister, I wrote. I felt better.

I tucked the foil in with the others and pulled out the card deck. I shuffled the cards, then scootched back on the couch and began laying them out. I played Black Hole long past when my back started to feel creaky and my eyes became heavy, thinking about summer camp and Noaychjon, who taught me a ton of solitaire games so I could play even when he needed a day off.

A part of me wondered if maybe on some level Noaychjon had known that one day I’d need to know those solitaire games, because one day I would be so utterly alone.

The screen door slammed, jarring me awake. I opened my eyes to see morning sun, and Kyle and Nathan racing down the walk with backpacks on, the whole time kicking at each other and stopping to bend over and pick up rocks and sticks and other things to be used as weapons.

“You poopface!”

“You dog’s butt!”

“You smelly farthole!”

I sat up, realizing when I found a card stuck to my arm that I’d fallen asleep while playing Black Hole. Some of the cards were on the floor. Others were underneath me, bent. I scooped them up, my fingers fumbling sleepily, and straightened them out as best I could, dropping them back into the box.

I stretched, then carefully opened the door and crept into the kitchen.

“I don’t see why she doesn’t have to go to school. Her house blew away, boo-hoo. She ain’t in Elizabeth no more. She’s here and she’s got a house,” Lexi was saying, her hip propped up against the kitchen counter while she shoved something bready into her mouth with her fingers. She made no attempt to hide that she was talking about me when I walked in.

“She ain’t registered here,” Grandmother Billie was saying. “And they told me not to even try it this year because school’s over in a week anyways, so it’s out of my hands.”

I walked on through, as if I didn’t hear anything, and carried my backpack to the bathroom. What business was it of theirs if I went to school or not?

I took a shower, trying to take as much time as possible, hoping the girls would be gone by the time I got out. It almost worked. They were standing by the front door waiting on my grandfather to take them to school, their things all gathered at their feet.

“It’s probably good you’re not going with us,” Meg said, pulling a red lollipop out of her mouth and waving it at me. Her lips and tongue were candy stained. “You’d probably embarrass us anyway. Hey, Lex, ain’t it perfect that her name’s a cow’s name?” She tapped Lexi on the forearm with her lollipop-wielding hand.

“Ew, gross, don’t touch me with that thing,” Lexi said, wiping her arm dramatically. “You’re such a child.”

“That’s enough now,” Grandfather Harold said, coming into the room, keys jangling in one hand. “Get yourselves to school and never mind this one.”

The girls glared at me and then pushed through the front door. While I was grateful that Grandfather Harold had made them leave, I couldn’t help noticing he’d called me “this one.”

I hurried into the kitchen, where Grandmother Billie was sitting at the table, drinking a cup of coffee and reading a paperback novel with a picture of a half-naked man on the front, wrapped around the torso of a woman in a gauzy white gown.

“There’s some dishes,” she said, without looking up. And even though my stomach was rumbling and I really didn’t think it was fair for me to have to do everyone else’s dishes when I hadn’t even eaten yet, I was afraid to say anything, so I went to the sink and started the hot water. “You get a chance to talk to my granddaughters yet?” Grandmother Billie said.

“Yes, ma’am,” I said. I didn’t mention them asking for money or calling me an orphan.

Her granddaughters. Clay was their dad. Grandmother Billie was their grandmother. And even though I shared the same blood, even though he was my father and she was my grandmother, too, nobody saw it that way. I was a stranger, pawned off on their family. I guessed Mom was right—family had nothing to do with blood. It had everything to do with what was in your heart. And there was nothing for me in any of the hearts in this house. The hearts that beat for me were long gone.

Just as I finished, Terry came into the kitchen and immediately began dirtying more dishes. A house this crammed with people seemed like it would never be free of dirty dishes, and I wondered if I would find myself permanently rooted to the spot in front of the sink, scrubbing and scrubbing until I wasted away to nothing. I wondered if they’d even notice that I was gone, and figured they would when the dirty dishes piled up, but that was about it.

“She don’t go to school?” Terry asked on a yawn.

Grandmother Billie grunted a negative, turning the page on her bodice-ripper.

I opened a few cabinets until I found some cereal and a bowl. Ordinarily, I wasn’t much of a cereal person, but today I was so ravenous I would have eaten anything, and I was too timid to search for something else. Too afraid that I’d break a rule I didn’t know about.

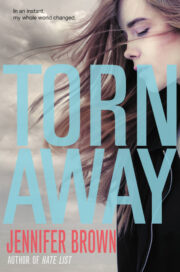

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.