“Mother tells me you need some clothes,” Terry said as I sat down across from her at the table.

I nodded, the cereal scraping the walls of my throat as I swallowed it without chewing very well. “I need to do some laundry, too,” I said.

“I’ve got a few things,” Terry said. “I can’t get into anything but my old maternity clothes, anyway. You might as well take them. After breakfast we’ll go through my closet if you want.”

“Thank you,” I said, setting the empty bowl down.

“Clay and Tonette home yet?” Terry said, turning back to my grandmother.

“Yep, they came in last night.”

Terry made a face and leaned toward me. “Never can be sure with those two. Some nights they come home; some nights they don’t feel like it. Some nights they land their sorry asses in jail.”

“Oh, that’s only happened twice, Terry, don’t be a ninny about it,” my grandmother said, but Terry only raised her eyebrows at me as if to say, See? It’s bad.

It sounded to me like not much had changed with my father. Like he’d remained the same old drunk he’d always been. In a way I was glad he’d abandoned me and Mom.

Grandmother Billie pushed away from the table, turning down the top corner of her page. Terry stood at the same time, so I figured it was best for me to get up, too, though I wasn’t quite sure what to do with myself. I wanted to watch TV but didn’t feel comfortable taking it upon myself to go into the living room and turn it on. Grandmother Billie didn’t make any offers or suggestions, either. Apparently when it came to doing the right thing for family, the right thing didn’t mean you did anything to make family feel welcome.

“Well, the housework ain’t gonna do itself,” Billie said. She placed her coffee cup in the sink and I tensed. Hadn’t these people ever heard of a dishwasher? She turned to me. “After you get some clothes from Terry here, you can get started on your laundry. Machine’s in the basement.”

She left the room, and soon after, the baby started to cry and I found myself standing alone behind the table. I took my bowl to the sink, then went back out to my porch to fold up my blankets and gather my laundry.

I decided to check in with Dani again.

Any news yet?

She responded right away. Doesn’t look good.

Tell your mom I’m sleeping on a couch on a porch. Please. I’m begging.

I’ll keep working on her, Dani promised.

When I dumped the laundry out onto the couch, there was a thump as something hard landed in the middle of it. I rooted through the clothes and found the source of the thump—the little porcelain kitten I’d taken from the rubble. The only thing left of my bedroom. The only remnant of my past life, other than memories. Memories I was terrified I’d forget.

Already, I was having a hard time picturing Mom’s face. I sat on the clothes, clutching the kitten in my palm, and closed my eyes, trying to conjure it up. But it was difficult to do; there were so many parts of her face I hadn’t studied enough. Her eyebrows—I couldn’t remember her eyebrows. I couldn’t remember which side of her mouth had the tooth that stuck out slightly, which side of her jaw had the little mole.

How was it that I was raised by someone, spent every day and every night with that someone, and didn’t know those details about her face? How could it be going murky and fuzzy already? How long would it be before I forgot what everyone looked like?

And then it dawned on me. My phone. I had pictures on my phone. Why hadn’t I thought of it before now? I grabbed it and quickly thumbed to the photo album, nearly crying out when I saw the very first picture—Dani and Jane, arms linked, standing in front of Jane’s locker. They had their eyes crossed and tongues sticking out. I’d taken it just a couple days before the tornado. I flipped to the next one—Jane and me, similar pose—and to the one after that and the one after that. My friends, my theater buddies, kids from my classes, Kolby showing off a new skullcap, all of us looking so happy, like life was one big party. I touched the faces on the screen. I stared at them until my eyes blurred. Afraid to blink, afraid they’d disappear. I scrolled and scrolled, surprised by how many pictures I didn’t remember taking.

And then a picture that made me freeze.

Marin’s birthday dinner at Pizza Pete’s. Ronnie had taken it. There was a humongous pepperoni pizza on a wooden picnic table. Mom and I were smiling for the camera, Marin making her signature funny face, her cheeks puffed with air and her fingers stretching her earlobes out.

I was flooded with a memory of the three of us—Mom, Marin, and me—standing in front of her bathroom mirror, studying our reflections. Mom had been getting ready for a date night with Ronnie, and Marin and I had wandered into the room like we always did when they were getting ready to go out, as if the party were leaving the house and we didn’t know how to have fun without them.

I had lifted Marin up onto the counter so she could see the mirror, and we watched as Mom put on her makeup, occasionally lifting our chins or pooching out our lips or turning our heads appraisingly from side to side.

“You have your father’s eyes,” Mom had said to me out of the blue, holding her mascara brush up in the air in front of her own eye.

“I do?”

She nodded, turning back to her reflection and applying the mascara. “Sometimes when I look at you, I can see him so strongly.”

I widened my eyes and peered at them. “Is that a bad thing?”

“Absolutely not. He’s a very handsome man. His eyes were actually what attracted me to him in the first place.” She capped the mascara and dropped it into her makeup bag, then rummaged around for something else.

“But you hate him now,” I said, thinking, How can you look at me without hating me, too?

Mom stopped rummaging and turned my chin to face her. “I hate what he did to us. But that’s not you. It never was,” she said. “It’s important for you to remember that. You may look like him, but you are your own wonderful person.”

“Who do I look like?” Marin had piped up. She pulled her ears out and puffed air into her cheeks, making a monkey face in the mirror. Mom and I both cracked up. Mom squeezed Marin’s cheeks, and the air came out with a farting sound, which made Marin laugh, too.

“You, girlfriend,” Mom said, playing with the back of Marin’s hair, “are the spitting image of your father. Who, by the way, is waiting on me, so I’d better finish up.”

The memory was so real. It was almost as if the picture on my phone had come to life. Tears clung to my lashes. My nose had started to run and I sniffed. I didn’t want to keep falling apart like this, but it seemed to keep happening without my even knowing it. Mom and Marin and I had fought so many times. That’s what happens when you’re family. We’d been ugly and called names. I’d stopped talking to Mom more times than I could count. I’d even told her I hated her.

But those weren’t the memories that assaulted me. The memories that came to me were worse—they were the ones where we were sweet, understanding, patient, kind. They were the ones that made my heart ache, because I’d never have the chance to build another.

In some ways, those were the cruelest memories of all.

I backed out of the photo album and put my phone away. I couldn’t look at those pictures anymore. I wiped my cheeks on the backs of my hands, thinking I would get up and dig out Marin’s purse. I would draw a picture of her making the monkey face. I would write Marin is the spitting image of her father.

But before I could move, the screen door opened and out came a pair of linty socks, topped with wrinkled blue jeans, the bottom cuffs all muddy, and a bare chest. Clay, clutching a beer can and belching loudly, stepped onto the porch. He let the door slam behind him and made a racket of pulling a folding lawn chair, one-handed, from behind a stack of stuff and clattering it to the floor across from the couch.

“So you’re Jersey,” he said, as nonchalantly as if he were small-talking some stranger in a bar rather than meeting his daughter for the first time in sixteen years.

I sat up straighter, feeling a desire to protect myself but unsure why or how. I was suddenly embarrassed to have my underwear spilled out all over the couch, and hoped I was sitting on most of it. I was also embarrassed to be caught crying and sniffed once more, hoping it wouldn’t show. Or that he’d be too hungover to notice.

“You’ve changed a lot,” he said, and I had to resist shooting back with Well, go figure. I don’t look like an infant anymore! “You look like your mother.”

“She always said I looked like you,” I mumbled, my thumb rubbing the kitten’s porcelain belly.

He laughed out loud, took a swig of his beer. “Did she now?” he said. “Well, go figure. Maybe you was mine after all. Crazy woman.”

“What do you mean?”

He leaned forward with his elbows on his knees. “I wasn’t the only well she was drinkin’ from at the time, if you know what I mean. Let’s just say there have been doubts about your paternity.” He overenunciated the word: “pah-ter-nit-tee.”

I shifted on the couch, uncertain if I understood exactly what he was trying to say. That I wasn’t his daughter? That Mom had been sleeping around? That wasn’t the Mom I knew. She’d always said we’d been a family—Mom and Clay and I—that he’d walked out on a promise.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” I said. “She never said anything about any of that. She was too busy trying to keep her head above water—until she met Ronnie.”

He had been in the middle of taking a drink, then stopped and pointed at me with his can-holding hand, one eye squinting while he swallowed. “Now, that’s one bastard I’d like to kick the shit out of,” he said. “Sending you down here like you was some lost coat I forgot to bring home with me sixteen years ago. Just decides he’s gonna screw with me and mine because he don’t want to deal with you. So what’s the story there? You a pain in the ass or something?”

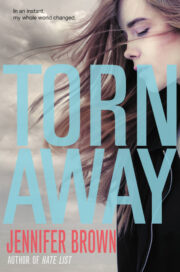

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.