I read every word of every story in the paper. I looked at all the photos, read the captions underneath them. I read the classifieds. Then, not ready to give up the feeling, I rambled through the aisles and ran my fingers along the book spines. Touching the titles, remembering good books I’d read, picking up new ones I hadn’t heard of and studying their covers.

I sat back in an armchair and read through most of a book. I didn’t have the money to buy it, so I forced myself to stop reading, feeling a little like I was stealing, even though I knew I only meant to steal the moment of sanity. When I got up and placed the book back on the shelf, I noticed that the café had closed and it was dark outside. Someone had pulled a safety gate about a quarter of the way down in front of the doors, and a voice over the intercom was telling us the store was about to close.

Reluctantly, I left, making a promise to myself to come back and visit again soon. Maybe scrape together some money and buy the book I’d been reading. Something, anything to make me feel normal again.

I was walking along the sidewalk, taking in the neon lights of business signs and the stars above that, when my phone rang. It was Jane.

“Omigod, Janie!” I squealed. “You’re okay!”

“Yeah, I’m fine,” she said. “I finally got a new cell phone yesterday. My old one got lost in the tornado. I’ve been dying to talk to everyone.”

“Dani said you’re in Kansas City?”

“Yeah. Staying with my uncle. Our house got wiped out. Afterward, we were climbing around trying to find stuff, and this big bunch of bricks fell on me and broke my leg in three places. I’m on stupid crutches for the whole summer. Can you believe that?”

At this point, I could believe almost anything. People think a tornado drops down on a cow pasture or a trailer park and everything is fine. They never think about things like infected cuts and broken legs and old ladies crushed by air conditioners in their bathtubs. They never think about orphans.

“Were you in the school when it happened?”

She chuckled. “Yeah. We didn’t even know anything was going on. We were practicing and never heard the sirens. We didn’t figure it out until the power went off, and then we heard all kinds of horrible noise, crashing and banging, like everything was falling down around us. But everyone was fine. Nobody got hurt or anything. And, thank God, my parents had gone to my brother’s soccer game over in Milton, so nobody was home. Our house is completely gone.”

“Mine, too. I have, like, nothing left.”

“I have my violin, and that’s pretty much it,” she said. “But the funny thing is, I don’t want to play it. At all. The only thing I’ve got left, and it’s still in my dad’s trunk.”

“It’ll come back.”

“I guess. Maybe. It just seems kind of pointless now, is all.”

So many things do, I wanted to say. “So are you going back to Elizabeth?” I asked instead.

“Yeah. My dad’s been down there all week clearing off our lot. I guess right now everybody’s just trying to get the debris moved out of the way. There was a minivan on top of my bed.” She laughed, then sobered. “Oh, hey, I’m really sorry about your mom and sister.”

“Thanks. It’s been pretty hard.”

“Yeah.” She took a breath. “Dani told me you’re staying with your dad in Caster City? I didn’t even know you had a dad. You never talked about one.”

“I didn’t have one. He’s just a jerk who shares my DNA. And he would argue that we don’t even share that much. I’m trying to get Dani to let me stay with her in Elizabeth. I can’t live here.”

“When everyone gets settled, you should come up to KC for a visit,” Jane said, and at last my heart lightened. My friends were coming through. “My cousin Lindy is a trip. You’d like her. I’ll ask my aunt.”

“Yeah,” I said. “I’ll call when I get out of here, and then I’ll come by.”

We talked for a few more minutes about things like where our friends had ended up, what would happen with graduation, given that we didn’t have a school and nobody really knew how many seniors were still in Elizabeth, and whether or not the movie theater was standing. It seemed like so long since I’d talked about anything other than the tornado, I hardly knew how to talk about other things. The conversation ended too quickly, as we both seemed to run out of things to say. When had that happened? When did I stop knowing how to talk to Jane?

I hung up the phone and continued walking but only got a few steps when a blast of a horn a few feet away made me jump.

“Where the hell you been?” Clay yelled, hanging out the car window. “Get in the damn car.”

At first I stood rooted in my spot. I had that “stranger danger” feeling that we were always warned about when we were kids. Don’t ever get into a car with a stranger, we’d been told. Trust your instincts. If your instincts tell you the situation is bad, stay away from it. Never get in the car with a dangerous person; never let him take you to another location.

But nobody ever told you what to do if you got those gut feelings about the man who was supposedly your father.

“What you starin’ at? Get in the car, I said!”

Swallowing nervously, I pulled open the passenger door and slid into the front seat, the ripped vinyl making dull tearing noises on the backs of Terry’s jeans.

He had the car in drive and was squealing away from the curb before I even got the door all the way closed.

“Been looking everywhere for you. My sister must have lost her damn mind,” he muttered, looking more at my hair than at the road in front of him. His tires bumped a curb and he quickly corrected, then overcorrected, the car swerving into the other lane and back again. “Lettin’ you color your hair, paying for it with money she ain’t even got. The two of you look ridiculous. And now my girls are feelin’ left out and Tonette ain’t gonna have ’em goin’ around lookin’ like that, that’s for sure. You keep tellin’ me I’m your dad, but you don’t even ask before you go and color your hair somethin’ stupid.”

I gritted my teeth, willing my mouth not to open, willing my ears not to hear him.

“You just gonna sit there like a loaf a bread?” he pressed.

But I continued to stare straight ahead, ramrod stiff on the torn passenger seat, watching him sway and swerve and knock into things like a pinball, clenching my teeth and my fists and my heart, feeling my resolve to stay silent crumble. If I didn’t speak up for me, who would?

“If you’re gonna leave the house, you need to tell someone you’re goin’,” he ranted.

“Why?” I said, turning on him.

He pulled up to a stop sign, glanced at me. “What do you mean why?”

“I mean why do I need to tell someone?”

He looked at me, incredulous. “So people don’t go worryin’, that’s why.”

I coughed out a laugh. “Who is worried? Tonette? Billie? Harold, who never even speaks to me? You? Give me a break. Nobody here cares about me.”

“That don’t give you the right to disobey the rules.”

I hadn’t wanted to get into it with my father, but I’d opened my mouth, and now there would be no shutting it again. “Lexi and Meg told me you didn’t want me here. Why did you agree to let Ronnie send me?”

He turned hard into a parking lot and screeched into a space. For a second, I got scared that he was going to do something dangerous. “I ask myself that every day,” he said, his nostrils flared. “Maybe ’cause Tonette’s right and I’m some sorta sap. Guess I figured after all these years of your mom keepin’ you from me, I deserved somethin’ outta you.”

We were staring at each other now, each of us with hate in our eyes. “What are you talking about?” I said. “She never kept me from you. You walked out on us. You never came back.”

A slow grin spread across his face and he began nodding as if it all made sense to him now. “Is that what she told you? That I walked out?” He tipped his head back against the seat and laughed, then turned to me again. “I got tossed out. Christine ‘wanted somethin’ better.’ ” He made air quotes with his fingers when he said the last three words, then jammed a stubby thumb at his chest. “I told her I could be somethin’ better, I’d get a job and stop drinkin’ and would take care of you. But she said she deserved more and I’d see you again over her dead body and that was that. And look. She’s dead and now here you are.”

“You lie,” I said through my teeth, but a part of me could tell that he wasn’t lying. A part of me could see it in the slight tremor of his thumb, could see it etched into the lines around his eyes. “You never wanted anything to do with me.”

His eyes hardened and he paused, sizing me up, the muscles of his jaw working. “Damn shame that’s the story she gave you. ’Cause it ain’t the truth.”

“It’s not a story. It is the truth,” I said, but my voice was wavering, getting softer.

He put the car into reverse and began backing out of the parking spot. “When I threatened to get the law involved, she started sayin’ you weren’t even mine.” He put the car into drive and glanced at me one more time. “I believed her at the time. She was some kinda messed up and I wouldn’t a put nothin’ past her at that point. But anyone with eyes can see we got the same DNA.” He pulled out onto the road and started heading toward the house again. “And then she was gone. Moved. Wasn’t the first time she’d disappeared on someone. I gave up. Met Tonette, started over. Forgot I even had a daughter named Jersey. Didn’t seem like there was anything else I could do.”

We drove along for a few minutes in silence, the town giving way to squat cookie-cutter homes. I wanted to get back to the house, to retreat to my couch and pull the blanket over my head, try to disappear from the lies, try to ignore the sinking suspicion that the liar was Mom, not Clay. Just thinking it made me feel like a traitor.

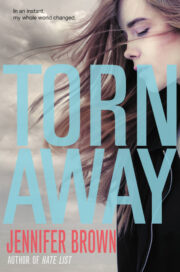

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.