She stayed, propped up by the door, for what seemed far too long, then finally sighed.

“Well, here, will this help, anyway?”

Curiosity kicked in and despite myself, I turned to see what “this” was. She reached around the doorframe and held out a phone.

“I thought you might want to call your friends. I’m sure you’re wondering what’s happening back at home.” She waggled the phone in the air. “You can talk as long as you need to. We don’t mind.”

I did want to call my friends, actually. Even though I had already talked to everyone that morning—everyone except Kolby, that was—and even though Dani’s mom had sold me out to Ronnie, I still wanted to talk to someone familiar. But if I took that phone from my grandmother, if I made that concession, she would think I wanted to be here. So I went back to staring at the photo silently and refused to look again until she had backed out of the doorway and shut the door behind her.

I’d purposely missed dinner. Had even crawled into bed and closed my eyes when she knocked, knowing she’d leave me alone if she thought I was asleep.

But I was starving, so when I stopped hearing the voices of the TV and the strip of living room light blinked out under my doorway, I crept to the kitchen. I froze when I found my grandfather sitting at the kitchen table, with only the light fixture above the table illuminating him. I noticed a traditional solitaire game laid out in front of him. He was missing an obvious black seven, red six.

“Patty left you a plate in the refrigerator,” he said when I walked in. “Pot roast. She makes the best in the world.”

I didn’t answer. I contemplated going back to my room. But I was so hungry, and pot roast sounded too good to be true.

I padded over to the refrigerator and found the plate, ripped off the plastic wrap, and heated the food in the microwave.

“We ask that you don’t eat outside of the kitchen,” he said, still not looking up from his game. He’d found the red six but had gotten stuck again.

The microwave beeped and I sheepishly took my plate to the table, after first pulling open every drawer in the kitchen to find silverware. He didn’t try to help me find it, and I was oddly grateful for his lack of effort. I sat on the end opposite my grandfather, keeping my eyes straight down on the plate.

He softly cursed and I heard him gather up the cards and shuffle them.

“She’s grieving, too,” he said, breaking the silence between us. I paused, then resumed chewing, still facing the pot roast, which was so tender it melted in my mouth. I hadn’t had anything this good to eat since the tornado. “Even though we hadn’t heard from Chrissy in sixteen years, your grandmother still hoped every day your mom would come around. So she’s grieving. She feels like it’s been sixteen years wasted.” He paused, the slapping sound of cards on the Formica telling me he was laying out a new hand of solitaire for himself. “We both do,” he added. “We didn’t even know about your half sister.”

“Sister,” I said, before I could stop myself. I felt my face flush with heat over having spoken.

“I stand corrected,” he said in a very matter-of-fact voice. Slap. Slap. “Your sister.”

I scraped the last bit of mashed potatoes onto my fork and licked it off, wishing I had another plateful. I got up and took my plate to the sink, rinsed it, placed it in the dishwasher, and poked through cabinets until I found one with drinking glasses. I filled a glass with tap water and took a big swallow. Everything felt too normal, too much like home. But this house wasn’t home for me. I wouldn’t let it be. Maybe this was what Mom meant by the oppression being contagious here. Maybe I’d already caught it.

“Anyway,” my grandfather said, as if he’d never stopped talking, though it had been several minutes since he’d last spoken, “you might find that you can help each other out, your grandma and you.”

I blinked at him, trying to convey my doubt with silence. He got stuck again and started flipping through the deck. He hadn’t moved the ace of hearts up to the top, which would have freed up a whole slot of cards. But I didn’t tell him that.

I walked to my bedroom and crawled back into bed, my stomach full, my eyes heavy.

I was asleep seconds after my head hit the pillow.

CHAPTER

TWENTY-TWO

When I got back to the bedroom after my shower the next morning, I found that my cell service had been turned off. I held the phone in my hand for a long moment and stared at it. I had expected it would be shut off at some point, but there was something so depressing and final about it. Like my last grasp on my old life had let go.

My grandmother had left a plate of Pop-Tarts on the dresser, along with a glass of apple juice. I wolfed it all down and sat on my bed, wondering what to do next.

I was well rested and my stomach was full. I didn’t want to watch TV, mostly because there was no TV in my bedroom, and I didn’t want to risk running into my grandparents in the living room. But I was getting bored and lonely with no entertainment, and though I wanted to make the statement that these people were to be loathed by me, I knew eventually I would have to come out and talk. I had nowhere else to go. Even I could admit, it wasn’t reasonable to believe I could live with my grandparents for the next year or more and not ever talk to them.

I grabbed the phone my grandmother had left on the dresser the day before and headed outside, where a striped patio swing looked out over an eager garden. I sat down, sinking my bare toes into the thick grass. I called Dani first.

“Do you hate me?” she asked.

“No. I wish you would have warned me, but I don’t hate you.”

She whispered into the phone. “It’s my mom. She thinks you’re going to have a mental breakdown or something, and she doesn’t want to have to be the one to handle it. Are you?”

“Am I what?”

“Are you going to have a mental breakdown? I mean, your mom died.”

“I know she died, Dani,” I said, trying to shake the irritation. Why on earth would her mom pull away from me if she thought I needed help? My mom had been right—Dani’s parents thought like lawyers. “And I don’t think so. I mean, I’m not sure. What does a mental breakdown feel like?”

“I don’t know. Like you’re going to lose it? I think I would be losing it if I were you.”

I pinched the bridge of my nose between my thumb and forefinger. I was feeling a too-familiar anger welling up inside me. I’d never been an angry kind of person, and it didn’t make sense why it kept coming back. I was sad, not angry. I was scared and lonely, but I didn’t understand why I felt so mad. Being mad all the time did sort of make me feel like I was losing it. “I guess,” I said. “It doesn’t matter.”

“Of course it matters.”

“Not to your mom.”

“Come on, Jersey. That’s not fair. My mom’s got a lot going on right now, too.”

Really? I wanted to scream into the phone. Like what? Did some shingles get damaged? Did she have to go without her blow-dryer for a whole week? Did the poor baby break a nail picking up a board in her driveway? How on earth did she possibly manage? Instead, I concentrated on my breathing, trying to will away the fury.

“Hello?” Dani said.

“I’m here.”

“Hey, um, not to change the subject, but I heard something about Kolby.”

I let go of the bridge of my nose and sat up straighter. “What?”

“It’s probably just a rumor, but someone said he got this weird infection in his arm.”

“Yeah. He did. I tried to call him a couple times. He was in the hospital over in Milton.”

There was a pause. “I heard it was pretty serious is all.”

“How serious?”

“I don’t know.”

But something in her voice told me she did know; she just didn’t want to say. I needed to talk to Kolby myself.

“Listen, I’ve got to go. I’ll call you back,” I said.

“Okay, but about my mom? Don’t be mad.”

Just let it go, my brain seethed. Let it go. “Yeah, it’s all right. I’m not,” I said. “I’m going to try to call Kolby again.”

“Call me back when you know what’s up,” she said. “Everybody’s wondering.”

“Okay,” I said.

I hung up and immediately dialed Kolby’s cell, pacing back and forth through the grass, kicking up swarms of tiny flying bugs.

“Hello?” Still not Kolby.

“Tracy? It’s Jersey. Is Kolby there?”

“Um. Jersey? Yeah, he’s here, but um… hang on.”

It seemed like it took a long time, but when the phone was finally picked up again, it was Kolby on the other end.

“Hey,” he said. He sounded bleary. “Are you back in Elizabeth?”

“No. I’m in Waverly with my grandparents. But what’s going on with you? Is it serious?”

“It’s fine. I got an infection in the cut on my arm. It’s some fungus spelled with about a thousand letters. The doctor said something about it being common after natural disasters.”

“Are you going to be okay?”

He cleared his throat, his voice craggy and clotted. “I guess it damaged a lot of tissue. Real gross-out stuff. Looked like something out of a comic book. I half expected a bionic arm to pop out.” He laughed weakly.

“But it’s healed now, right?”

“Sort of. They had to do a skin graft.” He chuckled. “They took skin off my butt and put it on my arm.”

I stopped pacing. “Wait. You had surgery?”

“Yeah. But I’m getting out of here soon. I have to relax for a while, make sure it heals up and stuff. Not a big deal.”

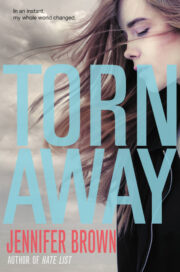

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.