‘Zenia,’ she said, ‘you look lovely. Who was your friend?’

Zenia blushed deeper. ‘His name is Vanya.’

‘He works for OGPU, I see. The Security Police.’

Zenia’s black eyes darted defensively to Sofia’s face. ‘I haven’t told him anything. About you, I mean.’

Sofia stepped nearer and could smell the musky scent of sex on her. ‘Zenia,’ she whispered, ‘the Security Police are clever. You will tell him things without even knowing you’re doing it.’

Zenia tossed her head scornfully. ‘I’m not a fool. I don’t say…’ but she paused as though remembering something and her eyes clouded. ‘I don’t say anything I shouldn’t,’ she finished defiantly.

‘I’m glad. Guard your tongue, for Rafik’s sake.’

Zenia looked away again.

‘It’s all right, Zenia, I won’t say anything.’

The dark eyes narrowed suspiciously.

‘I won’t say anything about Vanya. To Rafik, I mean,’ Sofia added.

Zenia smiled, a sweet, grateful smile that made Sofia lean forward and brush her cheek against the girl’s. ‘But be careful. They will be stalking Tivil village after what happened with the Procurement Officer and you may be their way in.’

‘He loves me,’ Zenia said simply and flounced away, young hips swaying and head held high, attracting glances from passing men.

‘He loves me,’ Sofia echoed, as if trying the words for size in her own mouth. Then she turned and retraced her steps through the shabby streets back towards the river.

26

Mikhail’s office was dark. Its small window let in a square patch of sunlight that was now sliding across the floorboards towards the door, as if trying to escape. He was often tempted to relocate to an office in the bright new extension he’d had built alongside the old factory, but always changed his mind at the last moment because he knew he needed to be here, overlooking the factory floor, visible to his workers each time they raised their heads from their machines. It discouraged malingering.

His office was up a flight of stairs that led off the vast expanse of the factory floor, so the incessant rattle and clatter of the bobbing needles were as much a part of his worklife as breathing. Nothing more than a wall of glass divided him from his workforce, which meant he could look down on the rows of hundreds of sewing machines and check the smooth running of his production line at a glance. He’d installed modern cutting machines in the extension but in here the machines were so old and temperamental that they needed constant attention, damn them. He had to watch them like a hawk because spare parts were like gold dust and the girls at the machines weren’t always as careful as they should be.

He stood looking out at them now, hands in his pockets, feeling restless and unable to concentrate. On his desk a stack of forms, permissions, orders and import licences awaited his signature but this morning he could summon up no interest in them. He loosened his tie and rolled up the white sleeves of his shirt. She’d unsettled him with her lies. With the challenge in her eyes, as though daring him to do something but refusing to say what it was.

He laughed out loud. At himself and at her. Whatever it was that Sofia Morozova was up to, he was glad she’d arrived in Tivil like a creature from the forest, wild and unpredictable. She made his blood flow faster. In some indefinable way she had altered the balance in his mind, so that he was left with the feeling that he was flying high in the air once more. He gave another laugh but then frowned and lit himself a cigarette, trying to breathe her in with the smoke. All kinds of memories were stirring, ones he’d thought were dead and buried but now were coming to life. They picked and prodded and chipped away at him so that he ached all over. What was it about Sofia that had set this off? Just because she was fair-haired and blue-eyed and had a fiery spirit like…?

No. He slammed the door shut on it all and firmly turned the key. What good did looking back do? None at all. He drew hard on his cigarette and exhaled over the glass, fogging it with smoke so that the women and their machines became an indistinct blur. He tried to imagine Sofia down there, working all day at one of the benches, but he couldn’t. It twisted his brain into shapes it refused to settle in. Sofia was a skylark, like himself. Too much of an individual in a country where individuality and initiative were stamped on by the relentless boot of the State. Conform or die. Simple.

A knock on the door distracted him.

‘Come in,’ he said but didn’t turn. It would be his assistant, Sukov, with yet another pile of endless paperwork for his attention.

‘Comrade Direktor, you have a visitor.’

Mikhail sighed. The last thing he wanted right now was an ignorant official from Raikom breathing down his neck, or a union inspector looking for trouble.

‘Tell the bastard I’m out.’

An awkward pause.

‘Tell the Comrade Direktor this bastard can see he’s in.’

It was Sofia. Slowly, savouring the moment, he turned to face her. She was standing just behind his assistant, eyes amused, breathing fast as though she’d been running and, even in her drab clothes, she made the office instantly brighter.

‘Comrade Morozova, my apologies,’ he said courteously. ‘Please take a seat. Sukov, bring some tea for my visitor.’

Sukov rolled his eyes suggestively, the impertinent wretch, but remembered to close the door after him. Instead of sitting, Sofia walked over to stand beside Mikhail at the glass wall and stared with interest at the machinists at work below. Her shoulder was only a finger’s width away from his arm. A faint layer of brick dust lay down the side of her skirt and on the angular bone of her elbow where she’d nudged against something. It made her look vulnerable and he had to stop himself from brushing it off.

‘A pleasure to see you again so soon – and so unexpectedly.’ He smiled and gave her a formal little nod. ‘To what do I owe this treat?’

She gave him a sideways glance, raising an eyebrow at his ironic tone, but instead of answering she tapped the glass with one finger.

‘The worker ants,’ she murmured.

‘They work hard, if that’s what you mean.’ He paused, studying the way her skin whitened under the curve of her jaw. ‘Would you really want to be one of them?’

She nodded. ‘It’s money.’ Abruptly she swung round to face him. ‘It’s very noisy in here.’

‘Is it?’

‘You mean you don’t notice?’

He shook his head. ‘I’m used to it. It’s quieter here than down there in the sewing room. I issue earplugs but half the women don’t bother to wear them.’

She looked out at the hundreds of heads bent over the machines. ‘What nimble fingers they have.’

‘They have to work fast to meet their quotas.’

‘Of course, the quotas.’

‘The curse of Russia,’ he said and touched her shoulder, just on the spot where a tear in her blouse was mended with tiny neat stitches.

She didn’t draw away. ‘It looks to me,’ she said thoughtfully, ‘as though the machines are working the women rather than the other way round.’

‘That is Stalin’s intention. No people, just machines that do what they’re told.’

‘Mikhail!’ Sofia hissed sharply and glanced towards the door. In a low whisper she warned, ‘Don’t talk so.’ Her eyes met his. ‘Please.’

The door opened and they stepped apart. Sukov entered with a tray that he set down on the desk with a show of attention that made Mikhail want to laugh. He was a pale-skinned young man with tight blond curls, who usually made a point of resenting any menial task now that Mikhail had elevated him from the tedium of quality control to Direktor’s Assistant. But he was well in with the Union Leaders and knew how to keep them off Mikhail’s back, so Mikhail tolerated his idiosyncrasies. He was astonished to see two pechenki on a china plate. Where on earth had Sukov found biscuits? A backhander from somewhere, no doubt. Mikhail would remember that.

‘Spasibo,’ Mikhail said pointedly.

Sukov rolled his eyes once more and tiptoed out of the room.

‘I apologise,’ Mikhail laughed as they settled down opposite each other at the desk, ‘for my assistant’s excessive discretion.’

‘Well, he must think it’s your lucky day. First one female visitor and now another.’

She said it with eyes sparkling, deliberately provoking him, but he wasn’t blind.

‘If you mean Lilya, she walked with me to the factory gates, that’s all.’ He picked up one of the glasses of tea in its podstakanik, a metal holder, noticed it had a picture of the Kremlin on it, swapped it for the other one with a picture of Lake Baikal and presented it to her. ‘She’s in need of a job.’

‘Like me.’

He offered her the plate with the two biscuits. She took one.

‘No,’ he said, ‘she’s not like you. Not at all like you.’

She bit into her biscuit, a crisp sharp snap.

‘Shall I tell you a joke?’ she asked.

Her words made him almost choke on his tea in surprise. ‘Go ahead.’

She leaned forward, eyes bright. ‘Two men meet in the street and one says to the other, “How are you?” “Oh, like Lenin in his mausoleum,” comes the reply. The first man cannot work it out. “What do you mean? Why like Lenin?” The second man shrugs. “Because they neither feed us nor bury us.”’

Mikhail threw his head back and roared with laughter. ‘That is very black. I like it.’

She was grinning at him. ‘I knew you would. But don’t tell it to anyone else because they may not see it quite the way we do. Promise me.’

‘Is that what we Russians are reduced to? Neither dead nor alive?’

‘I’m alive,’ she said. ‘Look.’ She put down her tea on the desk, raised her arms above her head and performed a strange kind of snake dance with them in the air. ‘See? I move, I drink.’ She sipped her tea. ‘I eat.’ She popped the rest of the biscuit into her mouth. ‘I’m alive.’ But her blue eyes slowly darkened as she looked at him across the desk and said softly, ‘I’m not dead.’

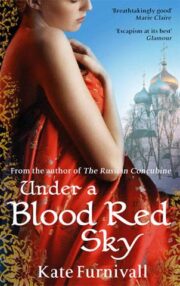

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.