A woman’s wrinkled face peered round the door.

‘Yes?’

‘I’m looking for Maria Myskova. I believe she may live here.’

‘Who wants to know?’

The woman was wrapped in a thick woollen headscarf, despite the heat of the day, and wore a dark brown blanket draped around her shoulders. In the gloomy hallway her head appeared disembodied. Her eyebrows were drawn together above what was clearly a glass eye, but her other brown eye was bright and intensely curious.

‘Who are you, girl?’ she demanded, holding out a hand for identification papers.

Sofia stood her ground without giving her name. ‘Maria used to live here with Comrade Sergei Myskov and his wife and child. On the first floor. Do you know where they are now?’

‘At work.’

‘You mean they still live here? When will they be home?’

‘Who wants to know?’ The woman’s eye gleamed.

‘Are you the dezhurnaya?’

‘Da. Yes, I am.’ She unwrapped the blanket enough to reveal an official red armband.

Everyone knew that caretakers were paid informers of the State Police, keeping a watchful eye on the comings and goings of their building’s inhabitants for OGPU. The last thing Sofia wanted was to rouse those wasps from their nest.

‘I’ll come back later if you’ll tell me when they-’

The crash of a piece of crockery followed by a man’s voice raised in a curse erupted from somewhere at the back of the hallway. The woman swivelled round with a squeal and scurried back into the shadows towards a door that was half open. Sofia didn’t hesitate. She stepped inside and leapt up the stairs two at a time, trying not to inhale the smell of boiled cabbage and unwashed bodies that seemed to breathe out of the fabric of the building. It brought the stink of the barrack hut at Davinsky Camp crashing into her head.

When she reached the first-floor landing she turned to her left, where a boarded window let in a few dim streaks of light. To her surprise, packed tight against the wall of the dingy corridor, were three beds, low and narrow. One was tidily made with a folded quilt, the second was a jumble of stained sheets and the third was occupied by a bald man stinking of vomit whose skin was yellow as butter. This was Sofia’s first experience of the communalka, the shared apartments where several families were crammed into the space that had once belonged to only one.

She squeezed past the first two and spoke in a whisper to the man in the third.

‘Do you need anything…?’

It was a stupid question. Of course the poor wretch needed something – something like a decent bed in a decent hospital with decent food and medicines and clean air to breathe, but he didn’t reply. His eyes were closed. Maybe he was dead. She felt she should tell somebody. But who? On tiptoes, so as not to wake him, she crept to the door at the end of the landing and knocked quickly. The door opened at once. A dark-haired woman stood in front of her, shorter than herself but broad across the bust. Sofia smiled at her.

‘Dobriy vecher,’ she said. ‘Good evening. I am Anna Fedorina.’

‘She’s dead. Maria died two years ago. Another stroke.’

The words were stark, but Irina Myskova spoke them gently.

‘I’m sorry, Anna, I know how much she cared for you. It’s so sad that she didn’t live to see you released.’

‘Tell Sasha that.’

The woman’s face stiffened at the mention of her son. His part in Anna’s arrest seemed to sit uneasily in Irina’s heart and she ran a hand across her large bosom, stilling whatever turmoil simmered there. Her clothes were neat but old, the material of her skirt darned in several places. The apartment was the same, clean and tidy with striped homemade poloviki rugs on the floor. Everything looked old and well used. Only the white plaster bust of Lenin gleamed new, and the bright red posters declaring Forward towards the Victory of Communism and We swear, Comrade Lenin, to honour your command. Sofia ignored them and looked across at the chair by the window. It was Maria’s chair, standing empty now, clearly not used by the family any more.

‘Sasha was only doing his duty,’ Irina insisted loyally.

Sofia hadn’t come here to argue. ‘Those times were hard and…’

‘But you’re looking well, Anna,’ Irina interrupted. She eyed Sofia’s new dress and her shining blonde hair thoughtfully. ‘You were pretty as a child, but now you’ve grown quite beautiful.’

‘Spasibo. Comrade Myskova, is there something of Maria’s I could have? To remind me of her?’

Irina’s face relaxed. ‘Of course. Most of her possessions have gone… Sold,’ she added self-consciously. ‘But Sergei insisted on keeping a few things back.’ She walked over to a cupboard and drew from it a book. ‘It’s Maria’s bible.’ She offered it to Sofia. ‘Maria would have wanted you to have it, Anna.’

‘Thank you.’

Sofia was touched by the gift. The feel of the book under her fingers, its pages so soft and well thumbed, raised a sudden sense of her own childhood and her own father’s devotion to bible study. She handled it with care.

‘Thank you,’ she murmured again and moved towards the door.

‘Wait, Anna.’ Irina came over and stood close.

‘What is it?’ Sofia felt an odd rush of sympathy for this woman, caught between her love for her son and her love for her husband’s dead sister. Gently she said, ‘What’s done is done, Irina. We can change the future but we can’t change the past.’

‘Nyet. And I wouldn’t wish to. But… if I can help you… I know from Maria that you were always fond of the Dyuzheyevs’ boy.’

‘Vasily?’

‘Did Maria tell you he came here once? He’s going under a different name now.’

‘Yes. Mikhail Pashin. She said he came twice.’

‘I wasn’t here, but I believe it was only once. Maria got confused sometimes. The other time it was a different man altogether who came to see her.’

‘Do you know who?’

‘Anna, I think you should know that the man had come trying to find you.’

‘Me?’

‘Da. It seems he was the young Bolshevik soldier, the one who shot your father and Vasily’s mother. He was searching for you.’

Sofia’s heart seemed to hang loose in her chest. ‘Who was he?’

‘That’s the odd thing. He said he’d been sent to work in a village in the Urals.’

‘His name?’

‘Maria wasn’t any good at remembering, but she told Sasha the name and he remembered it.’

‘What was it?’ She held her breath, and a sense of foreboding chilled her, despite the heat in the apartment.

‘Fomenko. Aleksei Fomenko.’

Mikhail didn’t sleep. The journey home was hard with no overnight stops. They slept sitting upright in their seats as the train ploughed its way through the darkness, its lonely whistle startling the wolves as they prowled the forests. Rain fell spasmodically, pattering against the black windows like unseen fingers asking to be let in.

Mikhail quietly smoked one cigarette after another and tried not to move too much in his seat. Sofia’s pale head lay on one shoulder, Alanya’s dark one on the other. He didn’t much care to be used as a pillow by the secretary and knew she would be embarrassed if she realised. Why Boriskin and Alanya had swapped seats he wasn’t sure, but he suspected it had something to do with the dressing down he’d given his foreman for declaring too accurate a picture of the labour problems at the factory.

His foreman had let him down badly. What was the point of bemoaning the lack of a skilled workforce in a peasant community when even a cabbage-head like Boriskin knew that such complaints would lose them important orders? And, more crucially, lose them the vital supply of raw materials. God knows, there was enough friction at the conference without adding to it needlessly. That was the trouble with some of these blasted jumped-up union men, they had no idea how to-

He stopped himself. He’d have to deal with Boriskin’s idiocy – or was it wilful incompetence intended to make Mikhail himself look bad? – back in the office. Not tonight. Tonight he’d had enough. Instead he brushed his cheek across the soft silk of Sofia’s hair and marvelled that even with the stink of his own cigarettes and a fat cigar smouldering with the man in the seat opposite, her hair still smelled fresh and sweet. Its fragrance reminded him of bubbling river water. He listened for her breathing but could hear nothing above the thunder of the wheels beneath him.

His own part in the conference had gone smoothly. The report he’d delivered to the Committee had been well received – it could hardly be otherwise, considering the production figures he was presenting to the hatchet-faced bastards – and his speech to the delegates in the hall had been suitably dull and steeped in boring numbers. No one had listened but everyone had applauded and congratulated him at the end. That’s the way it worked. You protect my back, I’ll protect yours. Mikhail took a long frustrated drag on his cigarette. No, he couldn’t complain about the conference. It was the rest of it that disturbed him on a much deeper level. The way Alanya attached herself to Sofia and stuck tight as a tick to her side so it was impossible for him to make time alone with Sofia. And then there was the small matter of her disappearance.

Damn it. Where did she go?

It was late in the evening before she returned, and to explain her absence he’d made up some claptrap about her attending a dinner with the members of the Party elite. But that had backfired because, when she reappeared, Alanya and bloody Boriskin had both fussed over her like mother hens and asked who had been at the dinner and what they’d had to eat. He chuckled to himself at the memory. Sofia had handled it brilliantly. She’d given Mikhail that slow mischievous smile of hers, then put a finger to her lips as she shook her head at Alanya.

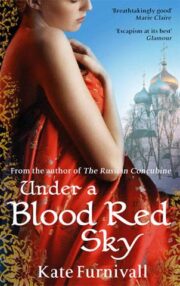

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.