‘No, that’s not the case. Every garment is routinely checked before it leaves the factory because any of the girls can make a mistake with her stitches.’

‘Saboteurs hide behind such platitudes.’

‘She is not a saboteur.’

‘But you are.’

Mikhail caught his breath. The room seemed to be closing in on him and his testicles throbbed in a steady sickening pulse from the beating in the cell. He spoke his next words clearly, ‘No, I am no saboteur.’

‘Don’t lie to me, you piece of dog shit. Can you deny that you spoiled three sewing machines last week, delaying production, on orders from your masters in Berlin?’

‘Yes, I do deny it.’

‘But the machines broke.’

‘Yes.’

‘You broke them. You are a filthy spoiler.’

‘No. They broke because they’re old.’

‘Just like you broke a turbine when you worked at the Tupolev aircraft factory.’

That caught him off guard. It was always the same, the questions twisted and turned, the accusations sliding under his carefully constructed defences.

‘No, the turbine broke because a part needed replacing, but-’

‘Were you well paid for that?’

‘I’ve already told you my salary at Tupolev’s.’

‘Well paid by your foreign paymasters for that treachery?’

‘That is insane. There were no foreign paymasters. I produced-’

‘Is that why you let the German firms palm off defective machinery on you?’ The mole eyes narrowed to slits.

‘The machines are-’

‘To sabotage quotas.’

‘We exceeded quotas last-’

‘Wrecker.’

‘No.’

‘Spoiler.’

‘No.’

‘Traitor.’

‘No! ’ He shouted it. To make it enter this man’s thick skull.

‘You try to deprive the Army of uniforms.’

‘I told you, I exceeded the set quotas.’

‘You lie.’

‘Look at the production figures of the Levitsky factory.’

‘You falsify the figures, you muddle up the numbers, you are a saboteur, a spoiler, a traitor.’ The man’s voice rose abruptly to a shrill command. ‘Confess.’

The room swayed. Or was it him? A fog seemed to thicken the air and a buzzing sound scraped his nerve ends as the electric light bulb spluttered and flickered briefly. His mind was trying to shut down. He closed his eyes. Somewhere inside the fog he heard a soft voice that whispered in his ear. You should take more care. It was Sofia, warm against his back on the horse, the feel of her breasts so close and her fingers tickling his ribs.

‘You bastards,’ he growled.

But again her solemn voice in his ear, You are too free with your insults.

Her words were real. This room could be nothing but a nightmare, a dismal wretched one. He opened his eyes, but the nightmare was still there in front of him, the interrogator leaning forward, his thumbs pressed together, his gaze full of distaste.

‘Confess.’

‘I am a loyal Communist.’

‘Spit that word out of your mouth, you filthy bourgeois capitalist. You are not fit even to speak of Communism. You don’t know the meaning of the word, you lie and you cheat and you take a traitor’s gold.’

‘No.’

‘You expanded the Levitsky factory, tying up a portion of the State’s investment finances that could have been used elsewhere. You were trying to undermine the Russian economy.’

This twist of logic finally dislodged Mikhail’s precarious temper. ‘You stupid bastard,’ he snapped, raising his hands as though to seize the man’s throat, ‘I expanded the factory in order to boost production and help the Russian economy. If you throw everyone who comes up with new and productive ideas into prison, this country will fall to its knees and weep.’

A silence settled and the room seemed to vibrate with it. Mikhail could hear his own laboured breathing. The interrogator opened the file in front of him, but his pale lips were working in anger and his eyes barely scanned the page.

‘You took in a kulak’s son,’ he stated. ‘The child of a Class Enemy. You don’t deny it because you can’t. The kulak was a Class Enemy who sabotaged the village mill. You all work together, you wreckers, in a conspiracy. Admit it. Confess. Sign this statement.’

‘No. I refute the charge.’

‘You are a Class Enemy. You steal from the State.’

‘No.’

‘You stole sacks of grain.’

‘No.’

‘I have a witness.’

‘They’re lying. It’s not true. Who is this false accuser?’

‘Your son.’

42

She wasn’t coming.

Pyotr leaned his forehead against the bleached wood of the meeting hall door, as if its warmth could still the chills inside him. He was alone and his heart ached for his father. He kept his back turned to the road because he refused to watch yet another villager pass by and turn their face away from him, as though he were invisible. Sofia wasn’t coming. He was an outcast even to her, a leper. Untouchable for the second time in his life – but what had he done? He kicked angrily at the door, rattling it on its ancient hinges.

‘Pyotr.’

She was here. He turned, relief filling his throat with that strange sort of honey taste that always came when he was near her.

‘Did you get it?’ she asked.

He nodded and held out his hand. Across his palm lay the heavy iron key to the meeting hall. It had grown warm from contact with his flesh.

‘Molodyets. Good boy.’ She snatched it from him. ‘Did they believe you? That you wanted to contribute to the kolkhoz by cleaning up the hall for them?’

He nodded again, but with the handle of the hazel-twig broom in his hand he pointed at one of the sheets of paper pinned on the door, the lists of that week’s individual achievements for each worker. His own name was on it. Time spent at the forge. Already someone had drawn a heavy black line through Pyotr’s name to show he no longer existed. He heard Sofia draw in breath sharply.

‘Shall I tear it down?’ she asked, as casually as if she were asking him if she should sew on a button.

‘No,’ he said, shocked.

‘Why not?’

‘No, don’t.’

Her hand lightly touched the hair on the back of his head. ‘Why not, Pyotr?’

‘It’s not… not…’ he struggled for the right word, ‘not wise.’

‘Why? Because Chairman Aleksei Fomenko put it up?’

‘There are soldiers,’ he told her in a whisper, ‘here in Tivil. I saw them.’

‘So did I.’

‘It’ll just make… more trouble,’ he muttered.

She took her hand away from his hair. No one had touched him like that since the night his mother went off with her soldier. Not even Papa.

‘Pyotr,’ she said, and her voice was so quiet he had to listen hard. ‘If everyone is frightened of making trouble, how will we ever make the world better? Even Lenin was a great one for making trouble.’

Pyotr hunched his shoulders.

‘The people of Russia will rot in their misery,’ she breathed, ‘like your father will in his cell. Like I did. Like Priest Logvinov will if he’s not more careful than he was today. Like all the other stinking prisoners will if we don’t make trouble, you and I.’

‘You were a prisoner?’ he whispered.

‘Yes. I escaped.’

It was like a gift. She was trusting him. He wasn’t invisible.

‘Open the door,’ he said. ‘I’ll help you.’

They searched the hall together, taking half each. Pyotr was quick as a ferret, darting from one likely spot to another, exploring it, moving on, eager to be the one to find the hiding place. She was slower, more methodical, but he could feel her frustration. His fingers wormed their way into cracks and scrabbled under benches seeking hidden compartments, but nothing yielded to his touch. Only the grey metal table with the two pencils and the two chairs he left alone because it was Chairman Fomenko’s territory. Pyotr felt like an intruder there. His cheeks were flushed but he didn’t want to stop, not now.

‘Do you know,’ Sofia’s voice came to him from across the body of the building, ‘that in the Russian Orthodox church, worshippers always stood? No benches to sit on and services could go on for hours.’

Pyotr wasn’t interested. Most of the church buildings had been blown up anyway. He pulled at a strip of plasterwork in the shape of an angel’s wing and it came away in his hand, but nothing lay behind it.

‘It was to prove their devotion, you see,’ she explained.

Why was she telling him this? She had her cheek against the opposite wall, eyeing the line of it, her fingers feeling for false fronts to the bricks.

‘Do you know why they had to do that?’ she asked.

‘No.’

‘It’s not that they had to prove it to God. They had to prove it to each other.’

Pyotr thought for a long moment and scratched at his head. ‘Like when we have meetings here and workers denounce each other for slacking in the fields that day. Is that what you mean?’

‘Exactly. It’s to prove to others what a true believer you are. To avoid damnation, in hell or in a forced labour camp. Both the same.’

He squatted down on his haunches and trailed a finger along the edge of a floorboard. He knew she was wrong, of course. Stalin warned against saboteurs of ideas as well as of factories, but he didn’t want to tell her that, not right now anyway.

His finger snagged.

‘Sofia.’

‘What is it?’

‘I’ve found something.’

She hurried across the hall. ‘What?’

‘This. Look.’

He lifted a filthy piece of string, no more than the length of a man’s hand. It was attached to one of the planks.

Sofia crouched at his side. ‘Pull.’

He yanked and a metre-long section of floorboard flipped up. Pyotr let out a shout and fell back on his bottom, but scrambled to his knees to peer into the gap. He’d found the hiding place. Now he would have the means to free Papa, that’s what she’d promised him. He didn’t know quite what it was they were searching for, except that it was in a box and it was definitely going to be something good. Sofia was tugging at the next section of flooring to widen the gap but it wouldn’t move, and for the first time he noticed the scars on her fingers.

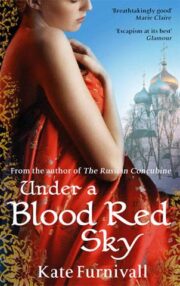

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.