‘Tell me what happened.’

‘I stood shoulder to shoulder with my father that day and mowed down the idle bourgeoisie like rats in a barrel.’ He turned his back on Sofia. ‘Why torment ourselves? You cannot despise me more than I despise myself for what I did. And the ultimate irony is…’ he gave a bitter laugh, ‘that all this time the boy who cut my own father’s throat that day has been living right here beside me in Tivil. Aleksei Fomenko turns out to be Vasily Dyuzheyev under another name.’

He slumped down in a chair at the table. ‘Neither he nor I recognised each other after all these years, but I hated him anyway for being the kind of person I used to be. And he hated me for having lost my faith. I was a threat. It didn’t matter how many quotas I exceeded at the factory, my mind wasn’t a Bolshevik mind and Fomenko wanted me to relearn the faith. He is a blind idealist.’

‘Don’t,’ Sofia said.

Mikhail looked at her and something wrenched in his chest. She was perched forward on the edge of his big armchair, her hair bright in a splash of sunlight, her eyes huge and sunken in her skull as though they could only look inward.

‘Sofia,’ he said gently, ‘until you came into my life I was incapable of loving anyone. I didn’t trust anyone. I despised myself and believed that others would despise me too, so I was wary in relationships. I went through the motions but nothing more. Instead I gave my love to an aircraft or a well-turned piece of machinery or…’ he gestured at the mess of wooden struts on the floor.

‘And to Pyotr.’

‘Yes, and to Pyotr.’ The hard muscles round his mouth softened. ‘When I came to this village six years ago, riding up the muddy street into my exile from Tupolev, and spotted this scrap of a child being tossed into a truck about to be carted off to some godforsaken orphanage, I saw Anna Fedorina in him, as she was on the doorstep all those years before – the same passion, the same fury at the world. So I carried the fierce little runt into my house and I petted and protected him the way I couldn’t protect her. I grew to love him as my own flesh and blood.’

‘But you still kept trying to find her.’

‘Yes.’ He cleared a space on the table in front of him, making room for his thoughts. ‘One day I did a favour for an officer in OGPU and in return he tracked down Maria for me. But I swear I only went there once, Sofia.’

Sofia nodded. ‘Maria muddled the two of you up in her head. She even told Irina the wrong names.’ Her words were heavy and lifeless. ‘Both tall with brown hair and grey eyes. She got it…’ she clenched her teeth, ‘… all wrong.’ Her gaze fixed on his face. ‘Like I did,’ she whispered.

‘No matter what happens now, I want you to know I love you and will always love you.’

She leapt to her feet, shaking her head violently. ‘No, Mikhail. I came here because I swore an oath to Anna. To find Vasily and to destroy the killer of her father if I could. Instead I’ve destroyed Vasily.’

50

Sofia begged. It pained Mikhail to see it, this wild independent spirit abasing itself.

‘Please, Rafik, please. I implore you.’

She was on her knees on the wooden floor before the gypsy, clutching his wiry brown hands in her pale ones, her lips pressed to his knuckles, her eyes unwavering on his face.

‘Please, Rafik, I beg you to do for Aleksei Fomenko what you did for Mikhail.’

The gypsy again shook his head. ‘No.’

The bedroom was small and gloomy. Mikhail found it acutely uncomfortable with six people crowded in. Candles thickened the air they breathed. Standing stiffly beside the bed were Pokrovsky, Elizaveta Lishnikova and the gypsy daughter, Zenia. Not one of them smiled a welcome.

What the hell was going on here?

The row of candles on the shelf sent out a twisting, shifting light that coated faces with touches of gold, while above them a giant eye on the ceiling stared down at a crimson cloth spread out on the bed. A white stone lay in the centre of it like a milky eye. Mikhail had the disturbing sense of having stepped into another universe, one that sent shivers down his spine. He wanted to laugh at it, to scoff at these grim faces, but something stopped him. That something was Sofia.

His heart went out to her as she knelt on the floor in supplication.

‘Help her, Rafik.’ He let his anger show. ‘You alter reality. Well, you alter hers.’

‘No, Mikhail,’ Rafik said, his black eyes intent on Sofia’s face, ‘I don’t alter reality. All I do is alter people’s perception of it.’

‘Please,’ Sofia whispered into the silence.

‘No.’ It came from Pokrovsky. His huge hands were still blackened from the forge but his presence in the room altered its balance in some important way. The bullet-shaped crown of his shaven head almost touched the eye on the ceiling. Whatever the force was that beamed down from that strange symbol, it made Pokrovsky a different man from the friend Mikhail had many times laughed with over a glass or two of vodka.

‘No,’ Pokrovsky repeated.

‘No,’ Elizaveta said in her clear precise voice.

‘No,’ Zenia echoed.

The silence shivered. Shadows tilted up and down the lengths of green curtain around the rough-timbered walls and the stone gleamed white on the bed. Sofia dragged a breath through her teeth.

‘Why, Rafik?’ she demanded. ‘It was my mistake, not Fomenko’s. I was the one who stole the sacks of food from the secret store in the church and hid them under his bed when he was out in the fields. You know no one locks their doors during the day here in Tivil. I broke that trust and I denounced him to Stirkhov. It wasn’t his dishonesty, Rafik, it was mine, I swear it.’ She pressed her forehead to his hands.

Rafik stepped back, removing his fingers from her grasp. His slight figure stood stiff and stern.

‘Sofia, I will tell you this. Chairman Aleksei Fomenko has taken from Tivil everything that belonged to the village by right and he has left us gaunt and naked. He has stripped the food from the mouths of our children to feed the voracious maw that resides in the Kremlin in Moscow. Above all else on this earth it is my task to protect this village of ours and that’s why I never leave it. If that means protecting it from Aleksei Fomenko at the cost of his life, so be it.’

‘So be it,’ intoned the others. The candle flames flared higher.

Sofia rose to her feet. She begged no more. Instead she moved to the door and Mikhail loved her for the proud way she walked.

‘Rafik,’ he said fiercely. ‘She needs help.’

The deep lines on Rafik’s face were etched white. He shook his head.

Mikhail strode to the bed and seized the stone. ‘Give her this.’

‘Put it back,’ Pokrovsky growled and took a threatening step towards Mikhail.

Rafik held up a hand. ‘Peace,’ he murmured. For a long moment the gypsy scrutinised the stone in Mikhail’s hand, then slowly he nodded. ‘Give it to her, Mikhail.’

Sofia’s eyes grew wide. He took her hand and placed the white stone cautiously on her palm, as if it might burn her, but the moment it touched her skin something in Sofia’s eyes changed. Mikhail saw it happen. Something of the wildness vanished and in its place settled a calm determination.

Please God, Mikhail prayed to the deity he didn’t believe in, don’t let her be harmed by it.

Pyotr was halfway through scraping burned clinker off a big flat shovel when he saw his father in the street. Pokrovsky had left him at the smithy with instructions to clean all the tools.

‘Papa!’ he called out.

A line of blue shadows was sliding down from the forest, slowly swallowing the village, so for a moment Pyotr missed the slight figure pacing beside his father, but the last rays of sun painted her hair almost red as she turned her face towards the forge. She waited in the middle of the road, still and silent in the dust, while his father came over. Somewhere a woman’s voice was raised in scolding a child. A dog barked. The wind stilled. An odd feeling crept over Pyotr, a sense of stepping over a line.

‘Papa,’ he said, throwing down the spade. ‘I’ve been thinking.’

His father smiled but it wasn’t a happy smile. ‘About what?’

‘About Chairman Fomenko.’

The smile vanished. ‘Don’t concern yourself, Pyotr. Finish up here and come home.’

‘I’ve worked it out, Papa. Chairman Fomenko would never steal from the kolkhoz, you know he wouldn’t. He’s innocent. Someone else must have put those sacks under his bed, someone vicious who wanted to-’

‘Leave it, Pyotr. The interrogators will have thought of that, I assure you. So forget it.’

Just then Sofia hurried over to them, her skirt tangling round her legs in her haste, her hair bobbing loose. ‘Pyotr,’ she called out, ‘you and I have work to do.’

She put her hand in her pocket and drew out the iron key.

All three of them searched the hall, but there was something wrong. Pyotr could feel it. He scuttled around between the benches, scraping at the floorboards with one of Pokrovsky’s knives, seeking another piece of string that would lead to a new hiding place. But all the time he was aware of the odd silences. They filled the hall, banging into the roof timbers and rattling the windows.

‘Have you searched in that corner, Papa?’

‘Sofia, look at this. The plank looks uneven here.’

‘What about that brick patched with cement?’

He kept up the chatter, filling the gaps, not letting the silences settle. Why didn’t they speak to each other? What had happened? But his words weren’t enough and the gaps were growing longer. As soon as they’d entered the hall and Sofia locked the door behind them, he noticed the way she and Papa wouldn’t look at each other. Had they quarrelled? He didn’t want them to quarrel because that might mean Sofia would leave.

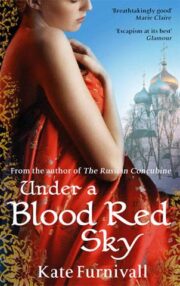

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.