‘Listen to me, comrade, and listen well. Vasily Dyuzheyev is dead and gone. Do not call me by that name ever again. Russia is a stubborn country, its people are hard-headed and determined. To transform this Soviet system into a world economy – which is what Stalin is attempting to do by opening up our immense mineral wealth in the wastelands of Siberia – we must put aside personal loyalties and accept only loyalty to the State. This is the way forward – the only way forward.’

‘The labour camps are inhuman.’

‘Why were you sent there?’

‘Because my uncle was too good at farming and acquired the label kulak. They thought I was “contaminated”.’

‘Do you still not see that the labour camps are essential because they provide a workforce for the roads and railways, for the mines and the timber yards, as well as teaching people that they must-’

‘Stop it, stop it!’

He stopped. They stared hard at each other. The air between them quivered as Sofia released her breath.

‘You’d be proud of her,’ she murmured. ‘So proud of Anna.’

Those simple words did what all her arguments and her pleading had failed to do. They broke his control. This tall powerful man sank to his knees on the hard floor like a tree being felled, all strength gone. He placed his hands over his face and released a low stifled moan. It was harsh and raw, as though something was ripping open. But it gave Sofia hope. She could just make out the murmur of words repeated over and over again. ‘My Anna, my Anna, my Anna…’ The dog stood at his side and licked one of its master’s hands with a gentle whine.

Sofia rose from her chair and went over to him. Tentatively her fingertips stroked his soft cropped hair, and a sweet image of it, longer, with young Anna’s fingers entwined in its depths, arose in her head. He had cut off Vasily’s hair as effectively as he’d cut off his heartbeat. Time alone was what he needed now, time to breathe. So she walked into his tiny kitchen to give him a moment, filled a glass with water, and when she returned she found him sitting in the chair, his limbs loose and awkward. She wrapped his hand round the glass. At first he stared at it, uncomprehending, but when she said, ‘Drink,’ he drank.

Then she squatted down on the floor in front of him and in a quiet voice started to tell him about Anna. What made Anna laugh, what made her cry, how she raised one eyebrow and tipped her head at you when she was teasing, how she worked harder than any of his kolkhozniki, how she could tell a story that kept you spellbound and carried you far away from the damp miserable barrack hut into a bright shining world.

‘She saved my life,’ Sofia added at one point. She didn’t elaborate and he didn’t ask for details.

Gradually Aleksei Fomenko’s head came up and his eyes found their focus once more, his limbs rediscovered their connection and his mind regained control. As Sofia talked, a fragile smile crept on to his face. When finally the talking ceased he took a deep breath, as though to inhale the words she had set free into the air, and nodded.

‘Anna always made me laugh,’ he said in a low voice. ‘She was always funny, always infuriating.’ The smile spread, wide and affectionate. ‘She drove me mad and I adored her.’

‘So help me to rescue her.’

The smile died. ‘No.’

‘Why not?’

He stood up, towering over her where she still crouched on the floor and he spoke quietly, the turmoil hidden away, concealed deep inside. His wolfhound leaned against his thigh and he rested a hand unconsciously on its wiry head.

‘You have to understand, comrade,’ he said. ‘Sixteen years ago, to satisfy my own anger and lust for vengeance, I slit a man’s throat. As a result Anna’s father was shot and her life destroyed. That taught me a lesson I will carry to my grave.’

His grey eyes were intent on Sofia’s face. She could feel the force of his need to make her understand.

‘I learned,’ he continued, ‘that the individual need doesn’t matter. The individual is selfish and unpredictable, driven by uncontrolled emotions that bring nothing but destruction. It is only the need of the Whole that counts, the need of the State. So however much I want to rescue Anna from her… misery,’ he closed his eyes for a second as he said the word, ‘I know that if I do so-’

He broke off. She could see the struggle inside him for a moment as it rose to the surface, and his voice rose with it.

‘You must see, comrade, that I would lose my position as Chairman of the kolkhoz. Everything that I have achieved here – or will achieve in the future – would be destroyed because they would revert back to old ways. I know these people. Tell me which counts for more? Tivil’s continued contribution to the progress of Russia and the feeding of many mouths or my and Anna’s…?’ he paused.

‘Happiness?’

He nodded and looked away.

‘Need you even ask? You’re blind,’ Sofia said bitterly. ‘You help no one, nor do you think for yourself any more.’

Something seemed to snap inside him. Without warning he bent down and yanked her to her feet, his fingers hard on her arms.

‘Thought,’ he said, his face close to hers, ‘is the one thing that will carry this country forward. At the moment Stalin is pushing us to great achievements in industry and farming but he is at the same time destroying one of our greatest assets – our intellectuals, our men and women of ideas and vision. Those are the ones I help to…’ He stopped and she saw him fighting for control.

His hands released her.

‘The radio in the forest,’ she said in a whisper. ‘It’s not to report to your OGPU masters. It’s to help-’

‘It’s part of a network,’ he said curtly, angry with her and angry with himself.

‘The previous teacher here who spoke out of turn?’

He nodded. ‘Yes.’

‘And others? You help them escape.’

‘Yes.’

‘Does anybody else in Tivil know?’

He drew in a harsh breath. ‘Only Pokrovsky, and he is sworn to secrecy. No one in the network knows of more than one other person within it. That way no one can betray more than one name. Pokrovsky provides… packages… and forged papers for them. Where he gets them, I don’t ask.’

Sofia recalled the ink stamp and magnifying glass on Elizaveta Lishnikova’s desk. She could guess. She also recalled Pokrovsky’s hard face when she accused him of working for both sides. She was angered at her own blindness and walked over to the open door, where she stood looking out at the village.

‘Chairman Fomenko,’ she said softly, ‘I feel sorry for you. You have hidden from yourself and from your pain so deeply, you cannot-’

‘I do not need or want your sorrow.’

But he came up behind her and she could feel him struggling with something, a faint hissing sound seemed to emanate from him. She could hear it clearly, though the room was silent.

‘What is it?’

She turned and looked into his grey eyes, and for a moment caught him unawares. The need in them was naked.

‘What is it?’ she asked again, more gently.

‘Tell her I love her. Take my mother’s jewels, all of them, and use them for her.’

She slid the damaged necklace from her pocket and slipped a single perfect pearl off its strand, took his strong hand in hers and placed inside it the pale sphere that had lain next to his mother’s skin. He closed his fingers over it. His mouth softened and she felt the tremor that passed through him. In the same moment she replaced the necklace in her pocket and removed the white pebble. With her other hand she rested her fingers on Fomenko’s wrist and pressed deep into his flesh as she’d seen Rafik do, touching the hard edges of his bones, his tendons, his powerful pulse, seeking him out.

‘Vasily,’ she said firmly, fixing her gaze on his, ‘help me to help Anna. I can’t do it alone.’

Something seemed to shift under her fingers. She felt it, as though his blood thickened or his bones realigned. A tiny click sounded in her head and a thin point of pain kicked into life behind her right eye.

‘Vasily,’ she said again, ‘help Anna.’

His eyes grew dark but his lips started to curl into a soft acquiescent smile. Her heart beat faster.

‘Chairman Fomenko!’ A boy’s voice shouted out from the street and a scurry of footsteps came hurtling up to the doorway. It was a clutch of seal-haired youths still wet from the pond. ‘Is it all arranged for tomorrow?’

Fomenko jerked himself back to the present by force of will and wrenched his wrist from her hold. His eyes blinked again to refocus on the world outside his head.

Sofia stepped out into the street. She’d lost him.

‘Is what arranged for tomorrow?’ he demanded.

‘The wagons to take everyone to Dagorsk. Like you promised last week.’ The boy’s face was grinning eagerly.

‘A holiday,’ chirped a blonde snippet of a child. ‘To see the Krokodil aeroplane and hear our Great Leader’s speech.’

Fomenko straightened his shoulders and gave a harsh cough, as though trying to spit something out. ‘Yes, of course, it’s all arranged.’ With a brisk nod of his head he moved back into the house and shut the door.

Sofia stood there while the boys raced away down the road, skipping over the ruts and yelling their excitement. The sky had darkened and a solitary bat swooped low overhead. She watched a yellow glow spring to life in Fomenko’s izba as he lit the oil lamp inside, but outside, Sofia felt no glow. Just the pain behind her right eye.

53

The night was unbearable without her. Mikhail spent the dark hours with his own demons and wrestled with the knowledge Sofia had given him.

Aleksei Fomenko. The name was branded into his brain. Fomenko was Vasily Dyuzheyev, the killer of his father. Yet at the same time Fomenko was the son of Svetlana Dyuzheyeva, the woman Mikhail himself had killed in cold blood.

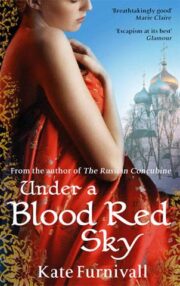

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.