But then again, perhaps I do.

Granddad has had too much to drink after a long travel day. “Shall we go inside?” I ask. “You want to sit down?”

He picks a second peony and hands it to me. “For forgiveness, my dear.”

I pat him on his hunched back. “Don’t pick any more, okay?”

Granddad bends down and touches some white tulips.

“Seriously, don’t,” I say.

He picks a third peony, sharply, defiantly. Hands it to me. “You are my Cadence. The first.”

“Yes.”

“What happened to your hair?”

“I colored it.”

“I didn’t recognize you.”

“That’s okay.”

Granddad points to the peonies, now all in my hand. “Three flowers for you. You should have three.”

He looks pitiful. He looks powerful.

I love him, but I am not sure I like him. I take his hand and lead him inside.

20

ONCE UPON A time, there was a king who had three beautiful daughters. He loved each of them dearly. One day, when the young ladies were of age to be married, a terrible, three-headed dragon laid siege to the kingdom, burning villages with fiery breath. It spoiled crops and burned churches. It killed babies, old people, and everyone in between.

The king promised a princess’s hand in marriage to whoever slayed the dragon. Heroes and warriors came in suits of armor, riding brave horses and bearing swords and arrows.

One by one, these men were slaughtered and eaten.

Finally the king reasoned that a maiden might melt the dragon’s heart and succeed where warriors had failed. He sent his eldest daughter to beg the dragon for mercy, but the dragon listened to not a word of her pleas. It swallowed her whole.

Then the king sent his second daughter to beg the dragon for mercy, but the dragon did the same. Swallowed her before she could get a word out.

The king then sent his youngest daughter to beg the dragon for mercy, and she was so lovely and clever that he was sure she would succeed where the others had perished.

No indeed. The dragon simply ate her.

The king was left aching with regret. He was now alone in the world.

Now, let me ask you this. Who killed the girls?

The dragon? Or their father?

AFTER GRANDDAD LEAVES the next day, Mummy calls Dad and cancels the Australia trip. There is yelling. There is negotiation.

Eventually they decide I will go to Beechwood for four weeks of the summer, then visit Dad at his home in Colorado, where I’ve never been. He insists. He will not lose the whole summer with me or there will be lawyers involved.

Mummy rings the aunts. She has long, private conversations with them on the porch of our house. I can’t hear anything except a few phrases: Cadence is so fragile, needs lots of rest. Only four weeks, not the whole summer. Nothing should disturb her, the healing is very gradual.

Also, pinot grigio, Sancerre, maybe some Riesling; definitely no chardonnay.

21

MY ROOM IS nearly empty now. There are sheets and a comforter on my bed. A laptop on my desk, a few pens. A chair.

I own a couple pairs of jeans and shorts. I have T-shirts and flannel shirts, some warm sweaters; a bathing suit, a pair of sneakers, a pair of Crocs, and a pair of boots. Two dresses and some heels. Warm coat, hunting jacket, and canvas duffel.

The shelves are bare. No pictures, no posters. No old toys.

GIVEAWAY: A TRAVEL toothbrush kit Mummy bought me yesterday.

I already have a toothbrush. I don’t know why she would buy me another. That woman buys things just to buy things. It’s disgusting.

I walk over to the library and find the girl who took my pillow. She’s still leaning against the outside wall. I set the toothbrush kit in her cup.

GIVEAWAY: GAT’S OLIVE hunting jacket. The one I wore that night we held hands and looked at the stars and talked about God. I never returned it.

I should have given it away first of everything. I know that. But I couldn’t make myself. It was all I had left of him.

But that was weak and foolish. Gat doesn’t love me.

I don’t love him, either, and maybe I never did.

I’ll see him day after tomorrow and I don’t love him and I don’t want his jacket.

22

THE PHONE RINGS at ten the night before we leave for Beechwood. Mummy is in the shower. I pick up.

Heavy breathing. Then a laugh.

“Who is this?”

“Cady?”

It’s a kid, I realize. “Yes.”

“This is Taft.” Mirren’s brother. He has no manners.

“How come you’re awake?”

“Is it true you’re a drug addict?” Taft asks me.

“No.”

“Are you sure?”

“You’re calling to ask if I’m a drug addict?” I haven’t talked to Taft since my accident.

“We’re on Beechwood,” he says. “We got here this morning.”

I am glad he’s changing the subject. I make my voice bright. “We’re coming tomorrow. Is it nice? Did you go swimming yet?”

“No.”

“Did you go on the tire swing?”

“No,” says Taft. “Are you sure you’re not a drug addict?”

“Where did you even get that idea?”

“Bonnie. She says I should watch out for you.”

“Don’t listen to Bonnie,” I say. “Listen to Mirren.”

“That’s what I’m talking about. But Bonnie’s the only one who believes me about Cuddledown,” he says. “And I wanted to call you. Only not if you’re a drug addict because drug addicts don’t know what’s going on.”

“I’m not a drug addict, you pipsqueak,” I say. Though possibly I am lying.

“Cuddledown is haunted,” says Taft. “Can I come and sleep with you at Windemere?”

I like Taft. I do. He’s slightly bonkers and covered with freckles and Mirren loves him way more than she loves the twins. “It’s not haunted. The wind just blows through the house,” I say. “It blows through Windemere, too. The windows rattle.”

“It is too, haunted,” Taft says. “Mummy doesn’t believe me and neither does Liberty.”

When he was younger he was always the kid who thought there were monsters in the closet. Later he was convinced there was a sea monster under the dock.

“Ask Mirren to help you,” I tell him. “She’ll read you a bedtime story or sing to you.”

“You think so?”

“She will. And when I get there I’ll take you tubing and snorkeling and it’ll be a grand summer, Taft.”

“Okay,” he says.

“Don’t be scared of stupid old Cuddledown,” I tell him. “Show it who’s boss and I’ll see you tomorrow.”

He hangs up without saying goodbye.

Part Three: Summer Seventeen

23

IN WOODS HOLE, the port town, Mummy and I let the goldens out of the car and drag our bags down to where Aunt Carrie is standing on the dock.

Carrie gives Mummy a long hug before she helps us load our bags and the dogs into the big motorboat. “You’re more beautiful than ever,” she says. “And thank God you’re here.”

“Oh, quiet,” says Mummy.

“I know you’ve been sick,” Carrie says to me. She is the tallest of my aunts, and the eldest Sinclair daughter. Her sweater is long and cashmere. The lines on the sides of her mouth are deep. She’s wearing some ancient jade jewelry that belonged to Gran.

“Nothing wrong with me that a Percocet and a couple slugs of vodka doesn’t cure,” I say.

Carrie laughs, but Mummy leans in and says, “She’s not taking Percocet. She’s taking a nonaddictive medicine the doctor prescribes.”

It isn’t true. The nonaddictive medicines didn’t work.

“She looks too thin,” says Carrie.

“It’s all the vodka,” I say. “It fills me up.”

“She can’t eat much when she’s hurting,” says Mummy. “The pain makes her nauseated.”

“Bess made that blueberry pie you like,” Aunt Carrie tells me. She gives Mummy another hug.

“You guys are so huggy all of a sudden,” I say. “You never used to be huggy.”

Aunt Carrie hugs me, too. She smells of expensive, lemony perfume. I haven’t seen her in a long time.

The drive out of the harbor is cold and sparkly. I sit at the back of the boat while Mummy stands next to Aunt Carrie behind the wheel. I trail my hand in the water. It sprays the arm of my duffel coat, soaking the canvas.

I will see Gat soon.

Gat, my Gat, who is not my Gat.

The houses. The littles, the aunts, the Liars.

I will hear the sound of seagulls, taste slumps and pie and homemade ice cream. I’ll hear the pong of tennis balls, the bark of goldens, the echo of my breath in a snorkel. We’ll make bonfires that will smell of ashes.

Will I still be at home?

Before long, Beechwood is ahead of us, the familiar outline looming. The first house I see is Windemere with its multitude of peaked roofs. That room on the far right is Mummy’s; there are her pale blue curtains. My own window looks to the inside of the island.

Carrie steers the boat around the tip and I can see Cuddledown there at the lowest point of the land, with its chubby, boxlike structure. A bitty, sandy cove—the tiny beach—is tucked in at the bottom of a long wooden staircase.

The view changes as we circle to the eastern side of the island. I can’t see much of Red Gate among the trees, but I glimpse its red trim. Then the big beach, accessed by another wooden staircase.

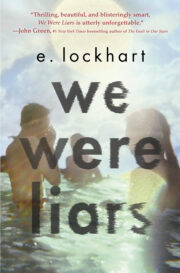

"We Were Liars" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "We Were Liars". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "We Were Liars" друзьям в соцсетях.